“The Grenada Revolution was a grasp of joy … that life unfulfilled could and would change, be transformed for a people who had known 400 years of transportation, slavery, colonialism, neocolonial dictatorship and exportation to the cities of Europe and North America. Joy that the organised genius of ordinary people could at last be applied to develop their own resources for their own future. There was the joy of education, of seeing your children achieving free secondary schooling and your illiterate mother learning how to read and write, the joy of seeing wasted, unemployed youths forming cooperatives and planting the idle land.” (Chris Searle, Grenada Morning)

Thirty-five years ago today, on the morning of 13 March 1979, the defence wing of the New Jewel Movement successfully overthrew the much-despised government of Eric Gairy. This bloodless coup – conducted by no more than 46 lightly-armed cadres – was widely welcomed by the people of Grenada. Hugh O’Shaughnessy writes that “the coup was enormously popular with Grenadians and it seemed as if the whole of the island was coming out into the streets to celebrate.” English popular educator and internationalist Chris Searle (who spent several years in Grenada and was charged with running both the teacher training programme and the official publishing house) notes that “fishermen, nutmeg workers, unemployed youth, peasant farmers and agricultural workers came streaming from their houses and converged upon police stations all over the island, forcing the policemen to run up white flags.” (Grenada Morning)

It seemed that the smog of subjugation, oppression and backwardness was finally being lifted; that this small southern Caribbean nation would be given the chance it deserved to blossom, freed from the iron grip of the kleptocratic and ruthless Eric Gairy – whose record of repression, personal enrichment, neocolonial policy, and alignment with the most reactionary states in the region (most notably Chile under Pinochet and Haiti under Duvalier) had lost him the trust and respect of the people.

Dennis Bartholomew, who during the period of the revolution was a representative of the People’s Revolutionary Government at the Grenadian High Commission in London, talks of the significance of the ‘revo’:

“From being the descendants of slaves, from people who’d been colonised, from people who’d been tossed aside, we suddenly became the controllers of our own destiny. For 400 years, our forebears were enslaved. We suffered in order to produce Europe’s wealth. After slavery we were further enslaved under colonialism. But in 1979, with our own ability, by our own efforts, we changed our course. Yes, others helped, but it was us.” (phone interview)

Dennis points out that the sense of jubilation and pride generated by the revolution was not restricted to Grenada – it spread like wildfire within the Caribbean community in Britain:

The effect was absolutely electric in Britain. Grenadians had previously kept their heads down – working, sending money home and so on. All of a sudden we felt extremely proud. An energy was there that wasn’t felt before. For example, the High Commission and the Caribbean community worked together to put on an event at the Commonwealth Institute to mark the anniversary of the revo. We were expecting maybe 500 people, and in the end 5,000 turned up. When Maurice Bishop was in London it was phenomenal – you couldn’t get into the meeting because of the crowds. The attitude of Grenadians changed. People were walking around who hadn’t been political before, and they started speaking in public in defence of Grenada, such was the pride.

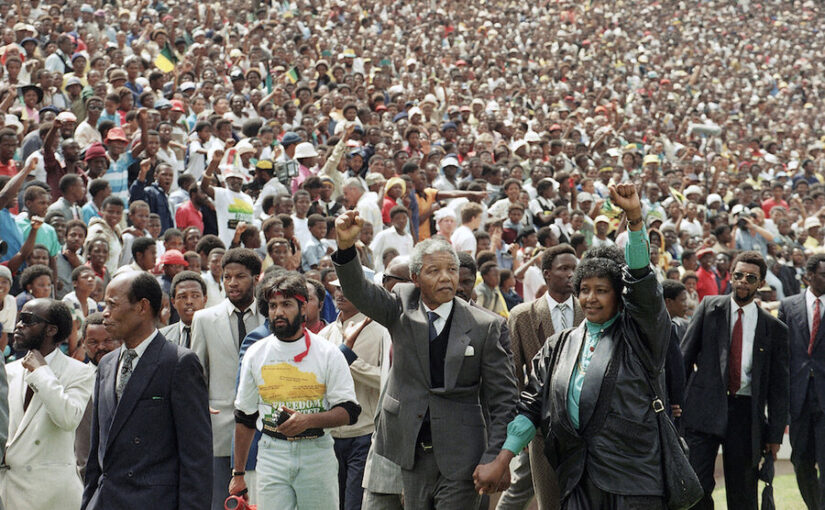

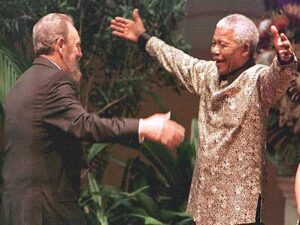

The excitement of the revo was felt all around the Caribbean, as well as in the Caribbean communities in Britain, the US and Canada. Grenada instantly became a pole of attraction for socialists, anti-imperialists and Black Power activists. The father or critical pedagogy, Paulo Freire, came to kick off the literacy campaign. Major figures from the US such as Angela Davis and Harry Belafonte visited Grenada and were deeply inspired. Cheddi Jagan, Michael Manley, Daniel Ortega and Fidel Castro all spoke of the profound importance of the Grenada revolution. The legendary Mozambican freedom fighter (then President) Samora Machel visited the island to show his solidarity. Progressive politicians, educators, activists and writers from throughout the region came to work in Grenada – figures such as Richard Hart, Merle Hodge, Didacus Jules and George Lamming. The truth is that this peaceful revolution in a small Caribbean country (with a population of a shade over 100,000) was a landmark moment, and its effects were felt throughout the region, and indeed the world.

The excitement of the revo was felt all around the Caribbean, as well as in the Caribbean communities in Britain, the US and Canada. Grenada instantly became a pole of attraction for socialists, anti-imperialists and Black Power activists. The father or critical pedagogy, Paulo Freire, came to kick off the literacy campaign. Major figures from the US such as Angela Davis and Harry Belafonte visited Grenada and were deeply inspired. Cheddi Jagan, Michael Manley, Daniel Ortega and Fidel Castro all spoke of the profound importance of the Grenada revolution. The legendary Mozambican freedom fighter (then President) Samora Machel visited the island to show his solidarity. Progressive politicians, educators, activists and writers from throughout the region came to work in Grenada – figures such as Richard Hart, Merle Hodge, Didacus Jules and George Lamming. The truth is that this peaceful revolution in a small Caribbean country (with a population of a shade over 100,000) was a landmark moment, and its effects were felt throughout the region, and indeed the world.

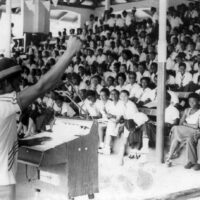

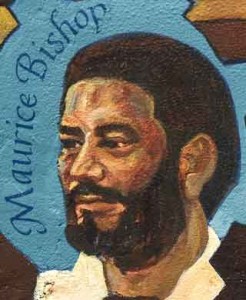

Maurice Bishop

The most prominent leader of this revolution was a charismatic young lawyer by the name of Maurice Bishop. Bishop was a popular, creative and intelligent revolutionary with an intuitive grasp of where the masses were at. A brilliant communicator, his mutual empathy with the masses of the people was one of the major driving forces of the revolution – not unlike the relationship between Fidel Castro and the Cuban people, or between Hugo Chávez and Venezuelan people. Fidel saw him as a true brother and comrade, remarking that “Bishop was one of the political leaders best liked and most respected by our people because of his talent, modesty, sincerity, revolutionary honesty and proven friendship with our country”.

The most prominent leader of this revolution was a charismatic young lawyer by the name of Maurice Bishop. Bishop was a popular, creative and intelligent revolutionary with an intuitive grasp of where the masses were at. A brilliant communicator, his mutual empathy with the masses of the people was one of the major driving forces of the revolution – not unlike the relationship between Fidel Castro and the Cuban people, or between Hugo Chávez and Venezuelan people. Fidel saw him as a true brother and comrade, remarking that “Bishop was one of the political leaders best liked and most respected by our people because of his talent, modesty, sincerity, revolutionary honesty and proven friendship with our country”.

Recently-deceased and much-missed veteran of the Caribbean labour movement Richard Hart wrote:

“By any standards he was a remarkable man. A lawyer by profession from a comfortable middle class background, his sympathies were nevertheless with the underprivileged masses. The initial emotional stimulus which he had received from the Black Power movement of the 1960s had ripened and matured during the 1970s on a more secure intellectual basis as he familiarised himself with Marxist-Leninist theory. Sentiment, theory and practice had combined to mould him into a dedicated revolutionary. He possessed to an extraordinary degree the ability to articulate clearly the objectives of the Revolution and to inspire support for it internally and regionally. His analytical mind and capacity for simple explanation helped the people to understand and share his convictions. His personality was magnetic.” (In Nobody’s Backyard (Preface))

Much like Fidel and Chávez, Bishop was a brilliant orator, uniquely capable of voicing the needs and aspirations of his people. Searle comments: “His bearing, a deep, mellow voice and superb command of the English language together with a continuous propensity to resort to the Creole vernacular, combined with his skills of persuasive and sophisticated speech that he had developed as one of the Caribbean’s most successful barristers, all fused to give a many-sided articulacy to his public speaking… He had an outstanding ability to create this sense of joy among his listeners.” (Grenada Morning)

There were of course other very important leaders whose role was decisive, but it’s clear that Bishop’s personal role as the pre-eminent leader of the Grenadian masses cannot easily be overstated.

Achievements

Having captured power, the New Jewel Movement quickly got down to the serious work of improving the lives of Grenada’s long-suffering people. As Bishop said in his first broadcast on Radio Free Grenada after the capture of power on 13 March 1979:

Having captured power, the New Jewel Movement quickly got down to the serious work of improving the lives of Grenada’s long-suffering people. As Bishop said in his first broadcast on Radio Free Grenada after the capture of power on 13 March 1979:

This revolution is for work, for food, for decent housing and health services, and for a bright future for our children

Wendy Grenade, a Grenadian lecturer in Political Science at the University of the West Indies, enumerates the key areas of focus for the revo: “raising levels of social consciousness; building a national ethos that encouraged a sense of community; organising agrarian reform to benefit small farmers and farm workers; promoting literacy and adult education; fostering child and youth development; enacting legislation to promote gender justice; constructing low income housing and launching house repair programmes; improving physical infrastructure and in particular the construction of an international airport; providing an environment that encouraged popular democracy through Parish and Zonal Councils etc.” All in all, a very different focus to that of any previous Grenadian government, and to that of most other Caribbean states.

Pre-revolutionary Grenada suffered with unemployment levels upward of 50%. Through the development of cooperatives, the expansion of the industrial base, the diversification of agriculture, the expansion of the tourist industry, and the creation of massive public works programmes, unemployment dropped to 14%, and the percentage of food imports dropped from over 40% to 28% “at a time when market prices for agricultural products were collapsing worldwide.”

Paulo Freire was invited to design and lead the implementation of a literacy programme, which was successful in all but wiping out illiteracy (the literacy rate increased from 85% to 98%). The leaders of the revo realised that an educational system must be established that broke away from the British colonial tradition and the inferiority complex that it sought to instil in its ‘subjects’. As Bishop elaborated: “The colonial masters recognised very early on that if you get a subject people to think like they, to forget their own history and their own culture, to develop a system of education that is going to have relevance to our outward needs and be almost entirely irrelevant to our internal needs, then they have already won the job of keeping us in perpetual domination and exploitation. Our educational process, therefore, was used mainly as a tool of the ruling elite.”

Searle observed an intense, widespread desire and demand for learning:

One of the first overwhelming truths and discoveries of the Revolution was that education was everywhere, it was irrepressible! It came at once from every side and at every moment. The dammed-up flood of four centuries of the people’s urge to know, to understand, to learn, to connect, to criticise, to express themselves, was unstoppable. At meetings, at rallies, at panel discussions, through songs, poems, plays and calypso, the message poured down upon the revolutionary leaders: Teach us, we want to know! Young and old, farmer and urban worker, fisherman and the woman cracking nutmegs, seamstresses and road-workers, all clamoured for more education, giving the cue for the slogan: Education is a must – from the cradle to the grave.

By 1983, 37% of the national budget was being spent on education and health. School fees were abolished; schools were repaired. “Free books, school uniforms and hot lunches were provided for the first time for the poor. Health care was made free and the number of doctors and dentists doubled.” (source)

For the first time, Grenadians had a very real say as to how public funds were allocated – via a People’s Budget that pre-empted the celebrated Porto Alegre participatory budget by more than a decade. Meanwhile, the economic growth rate averaged 10% during the years of the revolution. A World Bank memorandum on the Grenadian economy in 1982 stated: “The government which came to power in March 1979 inherited a deteriorating economy, and is now addressing the task of rehabilitation and of laying better foundations… Government objectives are centred on the critical development issues and touch on the country’s most promising development areas.” Hugh O’Shaughnessy notes that this was “as close to unstinted praise as that cautious institution was ever likely to come.”

For the first time, Grenadians had a very real say as to how public funds were allocated – via a People’s Budget that pre-empted the celebrated Porto Alegre participatory budget by more than a decade. Meanwhile, the economic growth rate averaged 10% during the years of the revolution. A World Bank memorandum on the Grenadian economy in 1982 stated: “The government which came to power in March 1979 inherited a deteriorating economy, and is now addressing the task of rehabilitation and of laying better foundations… Government objectives are centred on the critical development issues and touch on the country’s most promising development areas.” Hugh O’Shaughnessy notes that this was “as close to unstinted praise as that cautious institution was ever likely to come.”

Regarding agriculture, Searle writes that “there was increased enthusiasm to work on the land. The old pattern of the plantocratic estate, the hierarchical control of the expatriate landlord or the man in the ‘great house’ and the living death of laborious daily-paid work on land which was not theirs – all this was changing. The growth in cooperatives on the land and the collective stake in production and profit had brought many young people back to the land, and three farm training schools had been established to give these young farmers some basic expertise in agriculture and cooperative management techniques.”

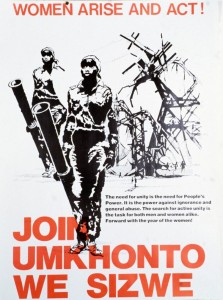

The revo was strongly focused on women’s empowerment and participation. “We moved against sexual harassment, and we encouraged women to participate fully in the construction of a new Grenada, for example through the National Women’s Organisation” (Dennis Bartholomew phone interview). Indeed, the first decree of the revo was to outlaw sexual victimisation.

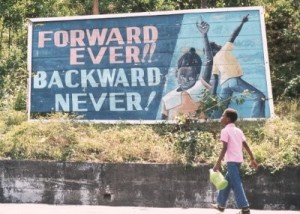

The changes in society were reflected by a massively invigorated national culture, expressed through calypso, poetry, dance and drama. “The shyness and reticence that characterised many of the Grenadian people before the Revolution, the self-consciousness of being a ‘small island’, second-rate or unnoticed was replaced by an explosion of national self-assertion through the revolutionary culture… More Grenadians were writing poetry and performing calypso than ever before, and receiving publication and air-play.” (Grenada Morning)

In terms of international relations, Grenada maintained friendly relations with all countries that were willing to treat it as an equal. Inevitably, this meant that its closest relations were with other nations within the socialist, progressive and non-aligned world, such as Cuba, (Sandinista) Nicaragua, the Soviet Union, Vietnam, East Germany, DPR Korea, Mozambique, Libya and Syria. Revolutionary Grenada was also a great friend to the forces fighting against South African apartheid and occupation, in particular the ANC and SWAPO.

We are a small country, we are a poor country, with a population of largely African descent, we are a part of the exploited Third World, and we definitely have a stake in seeking the creation of a new international economic order which would assist in ensuring economic justice for the oppressed and exploited peoples of the world, and in ensuring that the resources of the sea are used for the benefit of all the people of the world and not for a tiny minority of profiteers. Our aim, therefore, is to join all organisations and work with all countries that will help us to become more independent and more in control of our own resources. In this regard, nobody who understands present-day realities can seriously challenge our right to develop working relations with a variety of countries.

One of the most remarkable accomplishments of the revo was the construction of an international airport – the first airport to be built by a post-colonial Caribbean state. Bartholomew says with great pride: “The key step was building the international airport. It wasn’t built by the US or Cubans – we built it ourselves, with Cuban help. It was based on an old British plan. Money was raised internally by the raising of bonds, plus there was help from Libya, from Algeria, from Britain and elsewhere.”

Sadly, the revo didn’t live to reap the benefits of the airport, which wasn’t completed until 1984. In May 2009, the airport was finally renamed Maurice Bishop International Airport.

People’s Democracy

Revolutionary Grenada came under criticism from many angles for not holding parliamentary elections – particularly since Bishop’s first broadcast after the seizure of power had promised the restoration of “all democratic freedoms, including freedom of elections.” This lack of elections was constantly used by the US and its regional proxies to besmirch the New Jewel government, and there are plenty of people – even those broadly sympathetic to the revolution – who feel that the whole experience was tainted through lack of democracy.

Revolutionary Grenada came under criticism from many angles for not holding parliamentary elections – particularly since Bishop’s first broadcast after the seizure of power had promised the restoration of “all democratic freedoms, including freedom of elections.” This lack of elections was constantly used by the US and its regional proxies to besmirch the New Jewel government, and there are plenty of people – even those broadly sympathetic to the revolution – who feel that the whole experience was tainted through lack of democracy.

Why weren’t elections held? After all, there was never any doubt that the NJM would comfortably win at the polls. Bishop discussed this issue in an interview with New Internationalist in 1980:

We don’t believe that a parliamentary system is the most relevant in our situation. After all, we took power outside the ballot-box and we are trying to build our Revolution on the basis of a new form of democracy: grassroots and democratic, creating mechanisms and institutions which really have relevance to the people, If we succeed it will bring in question this whole parliamentary approach to democracy which we regard as having failed in the region. We believe that elections could be important, but for us the question is one of timing. We don’t regard it now as a priority. We would much rather see elections come when the economy is more stable, when the Revolution is more consolidated. When more people have in fact had benefits brought to them. When more people are literate and able to understand what the meaning of a vote really is and what role they should have in building a genuine participatory democracy.

Speaking at an event to mark the first anniversary of the revolution – an event at which the guests included Daniel Ortega and Michael Manley – Bishop highlighted some of the obvious flaws of the Westminster system:

There are those (some of them our friends) who believe that you cannot have a democracy unless there is a situation where every five years, and for five seconds in those five years, a people are allowed to put an ‘X’ next to some candidate’s name, and for those five seconds in those five years they become democrats, and for the remainder of the time, four years and 364 days, they return to being non-people without the right to say anything to their government, without any right to be involved in running their country.

In place of a such a pseudo-democracy, there was set up a system of grassroots democracy that, by any reasonable standard, must be considered far more democratic than the pretend democracy in place in Britain and the US. Thirty-five years later, Chris Searle remains immensely enthusiastic about the breadth of popular participation during those years:

“A lot went right. There were some unique developments. The internal democracy – the local democracy at the village and town level – was quite remarkable. Parish councils were set up; the women’s movement and youth movement were extremely active. It was a genuine mass mobilisation of ordinary people at every level, from the elderly down to children. There was nothing forced about it; the democracy bubbled up from the people. It was incredible, really.” (phone interview)

Organs of power sprung up everywhere, and nearly everyone was involved in some level of organisation and decision-making, be it the Zonal Councils, the Workers’ Parish Councils, the Farmer Councils, the Youth Movement or the Women’s Movement, all of which met at least once a month. Free facilities were made available for all such meetings, and they were often attended by senior government figures, who would have to answer directly to the people.

Bartholomew describes the atmosphere:

The feeling was totally different. People were coming together and doing things. Nobody said “we can’t do it”; they were saying “how are we going to do it”? There was a definite spirit in the air.

In 1981, the People’s Revolutionary Government established a Ministry of National Mobilisation, headed up by senior NJM leader Selwyn Strachan. This was a whole government ministry dedicated to devising means of continually spreading and improving popular participation in the running of the country, and ensuring maximum levels of accountability for those in positions of power.

Searle points out that the army was expected to be at the service of the people, and was deeply involved in helping to carry out decisions made by the organs of popular power. He states: “The army was involved and was extremely popular. if repairs needed or houses build, soldiers would be there.” Quite a difference from the role of the army in a typical bourgeois democracy!

So while parliamentary elections were not held in the four and a half years of the revo, a far more meaningful democracy was constructed. This had the additional benefit of avoiding the ways in which international imperialism – with its vast networks of contacts, diplomats, agents, media sources, bribes, and so on – can use parliamentary politics to subvert real democracy. Bishop’s analysis of this process brings to mind the way the west has tried to (and continues to try to) destabilise progressive governments, with varying degrees of success, in Jamaica (under Manley), Chile (under Allende), Venezuela, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Brazil and elsewhere.

“A part of that political tribalism, as used by the CIA, has been to get some of the parliamentarians to use the medium of parliament in such a way as to destabilise the country. Masterminded by their American puppeteers, they raise bogus concerns about the economy, they spread vicious propaganda from outside the country and seek to make the people lose faith and confidence in their revolutionary government, raising a million and one other such provocative matters through the medium of parliament – and thus claim to do it in that sense with a certain measure of legitimacy.” (Interview in mid-1983, contained in Grenada: The Struggle Against Destabilisation)

Destabilisation

Naturally, the revo was not too popular in the eyes of the politicians of the imperialist states. After all, Grenada was the first (and remains the only) English-speaking country in the Americas to have undergone a successful revolution of the oppressed. Moreover, it was a revolution led by the descendants of African slaves, and therefore was seen as a particularly dangerous example to the black population in North America. “The Grenada Revolution has a facility of speaking directly to the people of the USA, in particular the exploited majority. Then in the case of black Americans, meaning something like 27 million black people who are a part of the most rejected and oppressed section of the American population, US imperialism has a particular dread that they will develop an extra empathy and rapport with the Grenada Revolution, and from that point of view will pose a threat to their own continuing control and domination of blacks inside the US.” (interview, ibid)

On top of the bad example it was setting, Grenada was also considered a threat on account of its relations with countries on the wrong side of the ‘iron curtain’. Hugh O’Shaughnessy writes: “Washington’s rage reached paranoiac proportions when Grenada started close co-operation with Cuba and the USSR. Grenada’s action challenged the hegemony that Washington was expecting to extend throughout the Caribbean after the withdrawal of the British who had dominated it for two centuries.”

As can be seen from the example of so many states that have refused to go along with imperialist diktat – from Chile to Mozambique, from Cuba to Libya, from Venezuela to Syria – the west has a thousand different ways of creating instability. Grenada was no different. The US was able to mobilise elements within the Grenadian trade union movement to call strikes when the government was unable to meet their demands for enormous wage increases. There were boss-led lockouts. Production was sabotaged. Rallies were bombed. There were assassinations. A wide-ranging campaign was conducted in the ‘free’ (rich-white-owned) Caribbean press against the Grenadian revolution. In short, Grenada was subjected to every form of economic, political, paramilitary and media destabilisation. The revo was under constant threat.

We think of the scientific way in which they have evolved a new concept which they have called destabilisation: a concept aimed at creating political violence, economic sabotage; a concept which when it fails, eventually leads to terrorism. We think of the attempts to use local opportunists and counter-revolutionaries — people who try to build a popular base, people who fail in building that popular base, and people who as a result of having failed to fool the masses then turn to the last weapon they have in desperation: the weapon of open, naked, brutal and vulgar terror. Having given up all hope of winning the masses, these people now turn their revenge on the masses. They now seek to punish the masses, to murder them wholesale; to plant bombs in the midst of rallies; to try to break the back of the popular support of the Revolution; because imperialism was frightened and terrified by the Grenadian masses on March 13, 1980 when 30,000 of our people gathered in one spot to celebrate one year of People’s Victory, People’s Progress, People’s Benefits. They were terrified by that, and as a result they now seek to intimidate, to brow-beat, to frighten and terrorise the masses to get them to be afraid to assemble, to get them to be afraid to continue to build their own country in their own image and likeness.

In 1981, US President Reagan deployed over 120,000 troops, 250 warships and 1,000 aircraft to Vieques Island, near Puerto Rico, for a mock invasion. The operation was code-named ‘Amber and the Amberines’, in clear reference to Grenada and the Grenadines (which is Grenada’s full country name, as the state incorporates the two small islands of Carriacou and Petit Martinique). In this sinister war game, “the objective was to capture ‘Amber’, hold US-style elections and install a ‘government friendly to America’, keeping troops occupying the island until the elections were over.” (The Struggle Against Destabilisation). This was all too obviously an elaborate dress rehearsal for the US military invasion of Grenada.

Such is the dangerous and precarious context in which the revo existed.

Implosion and invasion

Constant destabilisation and psychological warfare had led to an atmosphere of fear, paranoia and mistrust among the leadership. Rumours were flying, tempers were frayed, emotions were running high, and people were feeling the sheer exhaustion of working day and night to build a new Grenada in the face of US threats and provocation. Searle writes that “if ever there was a time for forces hostile to the revolution to strike and mobilise themselves around the venomous use of rumours, this was the time. In the small islands of the Caribbean the rumour and the ‘bad talking’ are the deadliest of weapons, and during this time every rumour that moved from person to person, cadre to cadre and community to community contributed to the eventual destruction of the revolution.” (Grenada Morning)

Although the revo continued to make impressive gains, behind the scenes a factional dispute emerged within the New Jewel Movement in 1983, based primarily on a criticism of Maurice Bishop, who was accused of developing a personality cult and of succumbing to petit-bourgeois thinking. A parallel leadership started to emerge in the NJM Central Committee around Finance Minister Bernard Coard, one of the key figures of the revolution and its most respected theoretician.

How the divide degenerated to such an extent is, to this day, a matter of intense dispute. It seems that Bishop had initially agreed to a proposal for joint leadership of the revolution which was supported by a majority on the Central Committee. However, he came back from a trip to Hungary and Cuba in early October 1983 saying that he wasn’t sure about the workability of the plan and that he wanted to give it some more thought. This may have been a mistake on Bishop’s part, and the accusation that he was “in contempt of the party” may have been true. Nonetheless, the response of the Central Committee to place him under house arrest was indefensibly foolish. “On the Central Committee side there was a theoretical ‘purity’ which refused to compromise and seek a practical and creative solution… They knew Maurice had enormous popularity with the people and that to detain him in that sudden unexplained and provocative way would rile the support base of the revolution. To many thousands of people in Grenada, Maurice was the revolution.” (ibid)

Maurice Bishop was placed under house arrest on 13 October 1983. Once the word got out, rallies were held across the country demanding his release. Just a few days later, on 19 October, a demonstration of several thousand marched to his house and managed to free him. The situation was one of total chaos and confusion. The crowd marched to the military headquarters at Fort Rupert, where Bishop apparently believed they would be able to defend themselves and regain control of the country. Hundreds of Bishop supporters made their way to the fort, and army units under the command of General Hudson Austin – a longtime comrade of Bishop’s who was on the other side of the NJM dispute – came rushing to the scene.

Both sides claim that the other side fired the first shots. Fort Rupert came under heavy fire from the army. The first to fall dead was Vince Noel, one of the original 14 members of the Provisional Revolutionary Government. O’Shaughnessy writes that “the cry of panic and the groans of the dying and the wounded were almost effaced by the sound of hundreds of people rushing to escape wherever they could. Some ran down the incline back to town, others ran for cover in the General Hospital tucked below the fort, others threw themselves over the battlements to death or injury below, like so many lemmings… Within the operations room Bishop gave the order to stop any return fire on the attacking forces. In the last cry of anguish his followers were to hear, he moaned ‘Oh God, oh God, they turned their guns against the masses.'”

The army won control of the fort, and firing ceased. Those remaining in the fort were ordered to leave, with the exception of (Prime Minister) Maurice Bishop, (Minister of Education) Jacqueline Creft, (Foreign Minister) Unison Whiteman, (President of the Agricultural and General Workers Union) Fitzroy Bain, (Minister of Housing) Norris Bain, Keith Hayling, Evelyn Bullen and Cecil Evelyn Maitland. These eight were lined up facing a courtyard wall and executed by firing squad.

The army’s communique in the immediate aftermath struck a tone of curiously misplaced triumphalism: “All patriots and revolutionaries will never forget this day when … the friends of imperialism were crushed. This victory today will ensure that our glorious party the NJM will live on and grow from strength to strength leading and guiding the Armed Forces and the Revolution.”

The chaos – and the population’s shock at the sudden killing of the country’s leader and his closest comrades – created a favourable context for the US to enact its invasion plans, which had been “nursed in secret at the State Department and the Pentagon for four and a half years” (O’Shaughnessy). As the Cuban government’s statement the next day all-too-accurately predicted: “Now imperialism will try to use this tragedy and the serious mistakes made by the Grenadian revolutionaries to sweep away the revolutionary process in Grenada and place the country under imperial and neocolonialist rule once again.”

A week later, Reagan played out his ‘Amber and the Amberines’ war game in real life, sending tens of thousands of troops to ensure that the Grenadian Revolution was comprehensively wiped out. Thus was destroyed one of the most promising experiments in people’s power of the latter part of the 20th century.

There is much research still to be done in relation to the precipitous fall of Grenadian Revolution – the extent of CIA involvement, the details of the Bishop-Coard split, and so on. It’s almost impossible to understand how such a disaster could have happened, just as it’s almost impossible to understand how the Black Panthers and allied organisations in the US could have imploded so spectacularly. In the case of the Panthers, a great deal of research has been done over the decades, and we have an increasingly clear picture of the depth of the state’s sinister campaign of assassinations, imprisonment, psychological warfare, agents provocateurs, fake letters, rumour-mongering, and the infiltration of drugs. It would hardly be surprising if the US intelligence agencies turn out to have been heavily involved in the collapse of unity within the NJM.

Whatever the case, it’s difficult to disagree with Fidel’s assessment that “no doctrine, no principle or proclaimed revolutionary position and no internal division can justify atrocious acts such as the physical elimination of Bishop and the prominent group of honest and worthy leaders who died… Look at the history of the revolutionary movement, and you will find more than one connection between imperialism and those who take positions that appear to be on the extreme left.” The murder of Bishop and his comrades lost the NJM the trust and confidence of the people, and in so doing paved the way for US invasion.

Lessons and legacy

The great socialist former Prime Minister of Guyana, Cheddi Jagan, (himself the victim of imperialist destabilisation) spoke in 1981 of the inspiration that Grenada was giving to the whole Caribbean region:

“It is like a breath of fresh air, a tonic to the frayed nerves of a people long betrayed, battered and bruised … a monument to the Caribbean man’s courage and political will to stand up to imperialist diktat and blackmail.” (Grenada Morning)

It’s unfortunate that the Grenadian Revolution of 1979-1983 tends to be remembered only in terms of its tragic final days, because its first four and a half years were brilliant and unprecedented – an explosion of creativity, of culture, of vibrancy, of learning, of democracy, of freedom. The grandsons and grand-daughters of slaves wrested power and built a society on the basis of their own hopes and dreams. They began to write their own history.

The successes of the revo could continue to inspire progressive people around the world. The legacy of the New Jewel Movement should be kept alive, for how many other socialist movements in the English-speaking world have achieved so much? Dennis Bartholomew comments:

More than anything, we showed that if you have the will, and if you mobilise the people, you can change things. We were able to do remarkable things in spite of the fact that we started with a bankrupt economy and very little in the way of natural resources. But the people were mobilised. The memory hasn’t been totally wiped out. Thirty years later, we can make a clear comparison to help us understand what the revo did. In four and a half years of a progressive, independent, socialist-oriented model, look at what we achieved, and compare that with the achievements of 30 years of a US-backed capitalist model. Yes, the revo was tainted in the eyes of Grenadians as a result of the tragic events of 19 October, but the achievements can’t be forgotten. We shouldn’t forget the enormity of what we did.

Ultimately, the revo should not be seen as a failure. Do we consider the Paris Commune as a ‘failure’? The Soviet Union? The Haitian Revolution? Julien Fédon’s slave uprising in Grenada at the end of the 18th century? In the context of the broad historical epoch we are living through – the struggle to finally defeat colonialism, imperialism and racism, and to set the stage for the advance to socialism – such experiments cannot be considered as failures. Bishop himself put it well:

It took several hundred years for feudalism to be finally wiped out and capitalism to emerge as the new dominant mode of production, and it will take several hundred years for capitalism to be finally wiped out before socialism becomes the new dominant mode.

May the legacy of the Grenadian Revolution continue to inspire and educate.

Further study

- In Nobody’s Backyard: Maurice Bishop’s Speeches

- Maurice Bishop Speaks: Grenada Revolution, 1979-83

- Chris Searle – Grenada Morning: A Memoir of the ‘Revo’

- Hugh O’Shaughnessy – Grenada: Revolution, Invasion And Aftermath

- Chris Searle – Grenada: The Struggle Against Destabilisation

- Richard Hart – The Grenada Revolution: Setting the Record Straight

- Merle Hodge – Is Freedom We Making: the New Democracy in Grenada

- Chris Searle – Words Unchained: Language and Revolution in Grenada

- Film: Forward Ever – The Killing of a Revolution