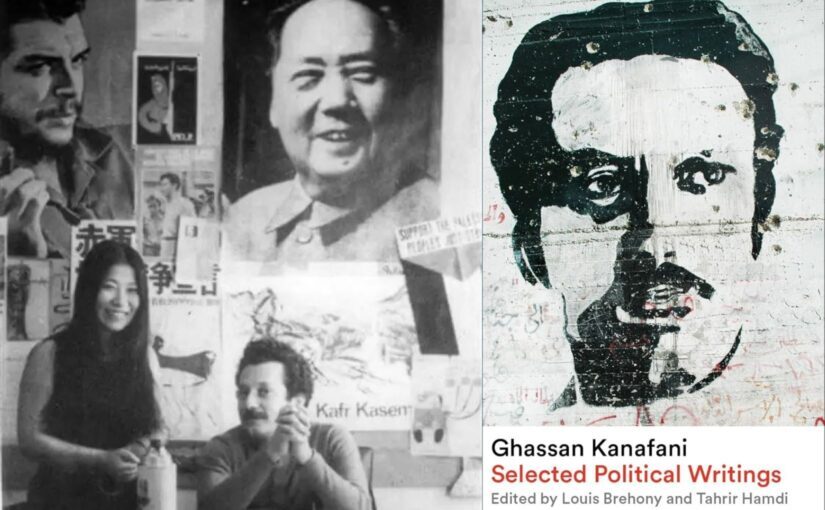

The following review by Carlos Martinez of Ghassan Kanafani — Selected Political Writings first appeared in the Morning Star.

This new volume from Pluto Press, edited by Louis Brehony and Tahrir Hamdi, brings together some of the most important essays, manifestos and journalistic reports by the revered Palestinian writer and activist Ghassan Kanafani.

Kanafani is best known for his literary works, all of which are deeply imbued with the spirit of anti-colonial resistance. His novels, short stories and essays, such as Men in the Sun (1962) and Returning to Haifa (1969), vividly depict the experiences of exile, dispossession and resilience, giving voice to the Palestinian collective memory.

Rashid Khalidi, in The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine observes that, “among the literary figures whose ideas and images played a major role in the revival of Palestinian identity, Kanafani was perhaps the most prominent prose writer and the most widely translated”.

Kanafani also made important contributions as a journalist, theorist and political activist. Indeed, the editors of Selected Political Writings consider that he was “Palestine’s greatest Marxist thinker. His ideas – forged in the firepit of war, crisis and armed resistance – are flammable materials, rich in the lessons of the revolutionary sparks which ignited his era.”

Kanafani was spokesperson of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP – a Marxist-Leninist organisation that forms part of the resistance front in Gaza today) from the time of its formation in 1969, and co-authored its program, Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine.

A powerful and consistent advocate of armed struggle against colonial occupation, and of the centrality of the working class and peasantry in the struggle for national liberation, Kanafani was deeply influenced by the ideas of Lenin, Ho Chi Minh, Mao Zedong and Fidel Castro, and situated the Palestinian liberation struggle within the broader global struggle against imperialism and for socialism. His two visits to China (in 1965 and 66) “left a comparably profound mark on his thinking”.

Indeed, on page 113 of Selected Political Writings, in an extract from Strategy for the Liberation of Palestine, we find: “The Palestinian and Arab liberation movement in alliance with national liberation movements in all undeveloped and poor countries will, in facing world imperialism led by the USA, find a strong ally to back its forces and augment its power of resistance. This ally is the People’s Republic of China.”

In a review for Counterfire, Michael Lavalette notes, with perhaps a hint of disapproval, that the PFLP’s Marxism was “heavily influenced by Third World, anti-colonial, armed struggles”. In Lavalette’s view, this is “not the classical Marxism of Lenin and Trotsky with its emphasis on the ‘self-emancipation’ of the working class”.

This comment brings Domenico Losurdo’s Western Marxism – recently reviewed in these pages – to mind. In their introduction to the English translation of that book, Jennifer Ponce de León and Gabriel Rockhill observe that “Eastern and Western Marxism … refer to two different political orientations… One of them is dedicated to the difficult and drawn-out process of building socialism in a capitalist-dominated world and, in particular, across the Global South, which has been the principal site for such endeavours thus far. The other is generally dismissive of such practical undertakings, often belittling concrete struggles against imperialism because they do not live up to an imagined standard of theoretical or moral purity.”

Kanafani’s writings and record of activity locate his thought very much within the sphere of Eastern Marxism. There is no “imagined standard of theoretical or moral purity”, and a great deal of “concrete struggle against imperialism”. He took tremendous inspiration from the construction of “actually existing socialism” and the revolutionary anti-colonial struggles waging around the world, and situated the Palestinian struggle within a global united front against imperialism.

In our struggle for the liberation of Palestine, we face primarily world imperialism… The major conflict experienced by the world of today is the conflict between exploiting world imperialism on the one hand, and these peoples [of Africa, Asia and Latin America] and the socialist camp on the other. The alliance of the Palestinian and Arab national liberation movement with the liberation movement in Vietnam, the revolutionary situation in Cuba and the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and the national liberation movements in Asia, Africa and Latin America is the only way to create a camp that is capable of facing and triumphing over the imperialist camp. (p113)

Interestingly, the PFLP was one of only a handful of organisations globally to successfully navigate the Sino-Soviet Split, maintaining good relations with both the Communist Party of China and the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. While clearly closer to China’s strategic orientation at the time, it recognised the Soviet Union as a “major supporter of the Arab masses in their fight against imperialism”, and benefitted from Soviet weapons, training and scholarships.

It’s also worth noting that the PFLP continues to maintain close links with People’s China. In July 2023, Deputy Secretary-General Jamil Mezher described China as a springboard for important global transformations that put an end to US imperialist hegemony and its savage policies in the world, and commended China’s constant support for the just causes of the Palestinian people in their struggle to restore their legitimate national rights.

Ghassan Kanafani’s ideas profoundly shaped Palestinian identity and resistance during a critical period of struggle against occupation and displacement. His influence was such that the Israeli foreign intelligence service saw fit to assassinate him on 8 July 1972. However, this despicable act (which can but remind us of so many other similarly despicable operations carried out by Mossad in the last 16 months), did not silence Kanafani, did not prevent his words from resonating. His clear-sighted and skilful application of Marxism-Leninism to the concrete reality of the Palestinian resistance has lost none of its relevance or its influence.

As Kanafani wrote, “the Palestinian cause is not a cause for Palestinians only, but a cause for every revolutionary, wherever they are, as a cause of the exploited and oppressed masses in our era” (p95). As such, Selected Political Writings deserves to be widely read. The editors have performed a most valuable service in making Kanafani’s political contributions available for readers of English.