Invent the Future editor Carlos Martinez was interviewed on the China Plus podcast World Today regarding the International Day for the Remembrance of the Slave Trade (marked annually on 23 August) and connected issues, particularly the continuing legacy of the Transatlantic slave trade, as manifested in systemic racism and a framework of international relations characterised by Western hegemony. The interview also addresses the startling hypocrisy of the US-led information warfare against China regarding human rights in Xinjiang.

Tag: racism

From Bristol to Boston to Hong Kong, the statues of colonisers and racists must fall

On 7 June, during an anti-racist rally in Bristol (part of the global wave of protests in the aftermath of the police murder of George Floyd), a group of protestors ripped a statue of notorious slave trader Edward Colston from its plinth and rolled it into Bristol Harbour. This act, although widely condemned by establishment politicians (Home Secretary Priti Patel for example describing it as “sheer vandalism”), was justly celebrated by anti-racists and anti-colonialists worldwide. A prominent member of the Royal African Company, Colston is estimated to have been involved in the enslavement of at least 84,000 Africans, nearly a quarter of whom died on the journey between West Africa and the Americas. People in Bristol – particularly its black community – have long campaigned for the statue to be removed, and have endured nothing but endless prevarication from the local authorities.

Colston’s upending was quickly followed by similar actions around the world. In Boston, Christopher Columbus was decapitated. In Richmond, Virginia, Jefferson Davis was toppled. (Davis was president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865 and a pro-slavery activist). The long-running campaign to remove Oxford University’s statue of the white supremacist and imperialist Cecil Rhodes has gathered fresh momentum. In Antwerp, Belgium, the statue of King Leopold II has had to be pre-emptively removed, while in Brussels, protestors climbed on a statue of Leopold and defiantly flew a giant flag of the Democratic Republic of Congo, which country suffered so terribly under Leopold’s brutal colonial rule.

Slavery and colonialism created the foundations of modern capitalism

This struggle around statues is immensely important. In Britain, statues of people like Edward Colston and Cecil Rhodes provide an uncomfortable reminder of just how much of Britain’s ‘greatness’ is built on a foundation of slavery, colonialism, plunder and genocide. The industrial revolution, which propelled Britain to domination in the early 19th century, started with the development of the steam engine. This scientific development was funded to no small degree with profits from the slave trade. Many of Britain’s cities blossomed as a result of “the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black-skins”, as Karl Marx so memorably put it.

For those of us that live in countries that have benefitted from colonialism, it’s crucial that we assess and understand this history. The primary beneficiary of colonialism and the slave trade was of course the capitalist class. However, ordinary people also benefitted to some extent. Indeed the ruling classes sought to justify colonialism on the basis that the profits resulting from it could be used to improve conditions for the working class and thereby maintain social stability. It was none other than Cecil Rhodes who said: “The Empire is a bread and butter question. If you want to avoid a civil war you must become imperialists.” Only by facing up to these uncomfortable facts can we hope to forge a path towards a united, non-racist and non-imperialist future.

The link between racism and imperialism

The tearing down of statues in the context of a global protest against white supremacy also reminds us just how closely linked racism and imperialism are. Columbus, Leopold, Rhodes, Colston and their ilk were racists and imperialists, and as representatives of a relentlessly expanding European capitalism couldn’t realistically be otherwise. Racism served as a justification for slavery and empire: “all men are created equal”, but that doesn’t apply to subhuman species. As capital spread into Africa, Asia and the Americas, so did a globalised racial hierarchy that continues to assert itself today on the streets of Minneapolis and elsewhere.

Just as racism in the colonial era served to prevent the working class in the imperialist countries from taking up the interests of the masses in the oppressed countries, racism in the modern era serves to divide the white working class in the imperialist countries from the masses of the developing world, and furthermore from minority communities originating in the developing world. The constant theme of racism is therefore its role in undermining solidarity between oppressed peoples.

So there is an inextricable link between racism and imperialism. Both are manifestations of national oppression, carried out by the ruling classes of the major colonialist countries (initially Britain, Spain, Italy, Portugal, Holland, Belgium and Germany, and later the US and Japan) as a means of perpetuating capitalism. This link between racism and imperialism is paralleled by the equally inextricable link between anti-racism and anti-imperialism. One cannot meaningfully oppose one manifestation of national oppression without opposing all manifestations of national oppression. To oppose racist policing is also to oppose the legacy of slavery represented by the likes of Edward Colston and Cecil Rhodes. It also means opposing imperialist wars, such as have been carried out against Syria, Libya, Iraq, Afghanistan and Yugoslavia. It also means opposing imperialist destabilisation and coercion, such as is currently being carried out against Venezuela, Zimbabwe, Iran, Cuba, Syria, DPR Korea, Nicaragua and other countries. It also means opposing attempts to reassert US global hegemony, currently gathering steam in the form of a New Cold War against China.

What statues should fall in Hong Kong?

Which brings us to the contentious issue of the protests in Hong Kong, a source of much confusion in the West. As Ajit Singh and Danny Haiphong have recently noted, some of the protest leaders in Hong Kong have attempted to associate themselves with Black Lives Matter, claiming a common cause against oppression and police brutality in spite of their close ties to some of the most reactionary and racist elements in US politics. Student activist Joshua Wong has gone so far as to accuse basketball star LeBron James of hypocrisy over his active support for anti-racist protests in the US and his lack of support for anti-government protests in Hong Kong.

The anti-racist protests taking place around the world in response to the gruesome murder of George Floyd are protests against national oppression, as discussed above. The attacks on the statues of racists, slave-traders, colonisers and imperialists are deeply connected to this movement. If black lives matter, the adulation of colonial oppressors must end.

So are the anti-government protests in Hong Kong also directed at racism and imperialism? If they are, wouldn’t we expect the protestors to be toppling the statues of Queen Victoria, King George VI and Thomas Jackson? After all Hong Kong is practically the quintessential example of colonialism. Incorporated into China since 214 BCE, it was seized by Britain in 1842 following the First Opium War, converted into a colony, and used as a base from which to direct British commercial operations, the most important of which was pushing opium onto the Chinese people. In 155 years of colonial rule, there were 28 British governors, with not a single one elected by Chinese people; Hong Kong was run essentially as an apartheid colony in which white people led a highly privileged existence.

Hong Kong was only returned to Chinese control in 1997, and thus a great deal of its colonial legacy remains. And yet the Hong Kong protestors don’t attack this legacy; in fact they are nostalgic for the days of British rule – waving union jacks and singing God Save the Queen – and they work closely with imperialist anti-China hawks like Tom Cotton, Marco Rubio and Mike Pompeo (all of whom, incidentally, are violently opposed to Black Lives Matter).

The only action Joshua Wong and his group have taken in relation to statues was to cover the Golden Bauhinia statue in black cloth ahead of President Xi Jinping’s visit to the city in 2017. The Golden Bauhinia statue was built in 1997 to celebrate the handover of Hong Kong and the establishment of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. So it turns out the Hong Kong protestors attack anti-colonial symbols, not colonial symbols. This amply demonstrates the fundamental difference between the global anti-racist protests and the Hong Kong ‘pro-democracy’ protests.

Toppling the statues of colonialists and white supremacists is a matter of global resistance against oppression. From Bristol to Boston to Hong Kong, the statues of colonisers and racists must fall.

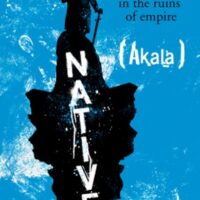

Book review: Akala – Natives

This article first appeared in the Morning Star on 24 May 2018.

Kingslee Daley — more often known as Akala — is earning a reputation as one of Britain’s most important voices.

On top of touring the world, releasing hip-hop albums, making documentaries for the BBC, campaigning on a range of issues, appearing on Question Time and running the Hip-hop Shakespeare Company, he has just published his first book.

Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire is at once a memoir, a detailed sociological investigation of racism and a whistle-stop tour of global politics from London to Beijing, with stops at Johannesburg, Kingston, Havana, Glasgow, New York, Hanoi, Bahia and Harare on the way.

We get an engaging and nuanced analysis of several themes, including the state of British culture, the historical function of racial superiority theories, the legacy of colonialism, the pernicious racism that can be found throughout our media and education system and the complex interplay between race and class.

The format is unusual — chapters tend to start with an episode from the author’s life and then go on to explore the sociological, cultural, political and economic relevance of that episode, making reference to a wide range of material, from academic papers to popular music. While this takes some getting used to, it helps to make the book accessible, as intellectual rigour is combined with human interest.

The overall ideological framework of the book is a pragmatic, socialist-oriented Pan-Africanism that seeks the liberation of all humanity from oppression and exploitation. At the same time, it highlights the shared problems faced by African communities worldwide in a global system of imperialism that is so inextricably linked with its origins in “the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black skins,” as Marx so memorably put it.

Akala demonstrates an impressive level of intellectual courage and doesn’t shy away from challenging deeply entrenched narratives, including the mainstream media’s coverage of China, Zimbabwe and Russia.

One important idea that emerges from Natives is that, in spite of Britain’s record of violence, slavery, genocide and colonialism, there is nonetheless a longstanding progressive trend that is “rooted in ideas of freedom, equality and democracy” and the author points out that while Britain was a leading proponent of war in Iraq, it was also the location of the world’s largest demonstration against that conflict. He also references the Chartists, the Tolpuddle Martyrs and the Suffragettes, along with the more recent examples of oppressed communities standing up for justice.

This broad progressive tradition is something that needs to be reclaimed and built upon. It provides a foundation on which we can build a redefined British culture, one that fights against injustice, that does away with racism, xenophobia and empire nostalgia, that celebrates diversity and that spurns “whiteness” — a solidarity of rich and poor based on the deception of race — in favour of the unity of the oppressed.

The historical moment we are living through demands nothing less. With the world moving in a multipolar direction, and with the rise of China in particular rendering theories of racial supremacy ever more absurd, the West is faced with a critical challenge. Will we cling on to our outmoded and anachronistic colonial-era ideology, fuelling ever-greater conflict and the threat of a re-emergent fascism and white nationalism, or will we embrace the future and seek to participate in the world as equal players on the basis of mutual respect and solidarity?

This question is being played out in an increasingly divergent political scene across Europe and the US. In Britain, while we’re witnessing the emergence of the Labour left, which is starting to establish a hegemonic position for anti-austerity, anti-war and anti-racist ideas, we’re also seeing a Tory government that has moved so far to the right that Ukip has basically lost its raison d’etre.

Natives constitutes a vital contribution to our understanding of modern society and poses a challenge for us all to participate in interpreting the past and moulding the future.

It deserves to be very widely read.

Immigration is a blessing for Britain. Don’t let xenophobic myths determine how you vote in the general election.

Tories resorting to xenophobia

It’s difficult to imagine an election campaign less imaginative and effective than the one the Conservative Party has been waging. Conversely, Labour’s campaign has been both convincing and compelling. Even in the eyes of many Labour MPs, Jeremy Corbyn was “unelectable and undesirable” just a couple of months ago, and yet, with just a few days to go until polling day, Labour are closing the gap on the Tories. When the election was announced, the YouGov poll had the Conservatives on 44 percent to Labour’s 23 percent. The most recent YouGov poll (at the time of writing), has the Conservatives on 42 percent and Labour on 38 percent, and there’s a very real chance that Theresa May will lose her majority. The days of Corbyn’s unelectability are well and truly over, to such a degree that even the Guardian has temporarily put its Blairism on the shelf and come out in support of Labour.

In a state of shock, the right-wing press and Tory campaign managers are pulling out all the stops to demonise Jeremy Corbyn and prove that he doesn’t care about the British people: he met with the IRA to try and push forward the peace process in Ireland; he has consistently voiced his reluctance to kill millions of people with nuclear weapons; he is “a pacifist relic of the 1970s, in hock to the trade unions”; and his shadow Home Secretary seems to perfectly well understand that Britain is systemically racist. Worst of all, he is not fanatically anti-immigrant, which apparently means he doesn’t want to protect British jobs and services.

The charge on immigration has been led by Rupert Murdoch’s flagship tabloid, The Sun. Corbyn is accused of “plotting to allow thousands of unskilled migrants to enter Britain.” Even worse, he has been outed for having made a speech in 2013 in which he described a racist anti-immigration crackdown as, well, racist. Shockingly for some, it seems that “Mr Corbyn has no intention of reducing the current sky high levels of immigration”.

Thankfully the reliably strong and steady Theresa May is here to save the day: “I want to ensure we are controlling migration, because too-high uncontrolled migration puts pressure on our public services, but it also lowers wages at the lower end of the income scale. I want to ensure we control migration. Jeremy Corbyn and the Labour party want uncontrolled migration.”

On this basis, the Tory election manifesto pledges to reduce net immigration to under 100,000 a year. A Conservative government will “work to reduce asylum claims” rather than doing the right thing and accepting more refugees; it will increase the minimum earnings required for a family member visa; and it will raise the Immigration Health Surcharge for foreigners using the NHS from £200 to £600.

By contrast, Labour “will not offer false promises on immigration targets or sow division by scapegoating migrants because we know where that leads.” The Labour manifesto (which clearly represents a compromise between the central leadership – particularly Diane Abbott and Jeremy Corbyn, both longstanding campaigners for immigrant rights – and more right-wing elements) calls for “fair rules and reasonable management of migration”, without setting any target. The manifesto commits a Labour government to getting rid of the family member minimum income visa threshold, and to reinstating the Migrant Impact Fund. It promises that “Labour will not scapegoat migrants nor blame them for economic failures.”

Is immigration bad for Britain?

That immigration has “shattered social solidarity, driven down living standards, fuelled job insecurity and imposed a completely intolerable burden on the civic infrastructure” has become received opinion for a large part of the British population. This is hardly surprising, given that it’s a viewpoint constantly reinforced by the media and politicians. However, it’s worthwhile taking a more serious look into whether it’s actually true.

Does immigration drive down wages? Inasmuch as there’s a simple answer to this question, it’s “no”. Diane Abbott puts it well: “Immigrants in and of themselves do not cause low wages. Predatory employers, deregulated labour markets and weakened trade unions – they cause low wages.”

At the most simplistic level of analysis, it’s obviously true that an increased workforce can have the effect of reducing wages through the usual action of supply and demand – higher supply of labour leads to reduced price of labour (wages). However, immigration also changes that balance in a different direction, by widening the market for the product of labour (goods and services), thereby increasing labour demand. Economists are almost unanimously agreed that this positive effect far outweighs any negative effect. Alex Tabarrok, professor of economics at George Mason University, writes: “Immigration unleashes economic forces that raise real wages throughout an economy. New immigrants possess skills different from those of their hosts, and these differences enable workers in both groups to better exploit their special talents and leverage their comparative advantages. The effect is to improve the welfare of newcomers and natives alike.”

The overall effect of immigration is to increase wages and create jobs. Giovanni Peri, labour economics expert at the University of California, argues that the average US worker earns around $5,000 more than they would have done were it not for the immigration to the US since 1990. “As young immigrants with low schooling levels take manually intensive construction jobs, the construction companies that employ them have opportunities to expand. This increases the demand for construction supervisors, coordinators, designers, and so on. Those are occupations with greater communication intensity and are typically staffed by US-born workers who have moved away from manual construction jobs. This complementary task specialisation typically pushes US-born workers toward better-paying jobs, enhances the efficiency of production, and creates jobs.”

At the individual level, there are no doubt cases where an immigrant labourer is willing to work for a lower wage than their British counterpart and thereby deprives the latter of a job, but these cases are relatively rare, and the solution is to demand decent wages and conditions for all workers. In general, where wages go down and jobs disappear, this is a function not of immigration but of casualisation, economic deregulation, de-industrialisation, ruthless profiteering, mechanisation and other macroeconomic factors.

And what about public services? Is immigration placing an intolerable burden on the housing, education, health and benefits systems? Again, the answer is no. “There is now a fairly large body of research on the fiscal impact of immigration, all of which says roughly the same thing: immigrants are generally net contributors to the British economy, paying more into the system in taxes than they take out by accessing public services… In 2009 the Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM) at University College London found that migrants from the A8 countries of central and eastern Europe who joined the EU in 2004 were 60 per cent less likely than native-born Brits to claim benefits, and 58 per cent less likely to live in council housing.”

Public services are suffering because they receive insufficient investment, not because of excessive demand from people born outside the UK. Incidentally, if there were greater investment in services, there would also be more jobs – good, socially useful, dignified ones at that.

Philippe Legrain contributes another argument which is more subtle but equally important: the diversity of skills, opinions, traditions and needs that immigrants bring is a significant contributor to economic growth.

It is precisely because newcomers are different that they are so beneficial, since their differences tend to complement local needs and conditions. They may have skills that not enough Britons have, like medical training or fluency in Mandarin. They may have contacts that open opportunities for trade and investment as the centre of gravity of the global economy shifts east and south. They may be more willing to do gruelling jobs that most British people with higher living standards, education levels or aspirations spurn, like picking strawberries or caring for the elderly. They may simply be young and hard-working, a huge bonus for an ageing society with a shrinking local workforce and increasing numbers of pensioners to pay for. Having moved once, they tend to be more willing to move again, enabling the job market to cope better with change. And their diverse perspectives and experiences help provoke new ideas, while their dynamism tends to make them more entrepreneurial than most.

In advanced economies like Britain’s, sustained rises in living standards come from finding new and better ways of doing things and deploying them across the economy… Innovation mostly emerges from creative collisions between people – and two heads are only better than one if they think differently. A growing volume of research shows that groups with a diverse range of perspectives can solve problems – such as developing new medicines, designing computer games and providing original management advice – better and faster than like-minded experts…

Thus immigrants make the economy more dynamic – and far from putting unbearable pressure on jobs, public services and housing, they help improve the locals’ lot. Newcomers create jobs as well as filling them – when they spend their wages and in complementary lines of work. Polish builders create jobs for British architects, supervisors and suppliers of building materials. Overall, migrants tend to boost local wages, precisely because of those complementarities. Falling real wages in recent years are due to the crisis, not immigration.

As Richard Osborne puts it in his book Up The British, “Immigration and refugees can quite conceivably be seen as the motor of cultural and intellectual energy in the British experience over the centuries”.

In summary, immigration is profoundly valuable for British society, and to significantly reduce it would be to commit economic suicide. Even the Economist, hardly a bastion of progressive political opinion, notes that, according to calculations by the government’s fiscal watchdog, reducing annual net migration to 100,000 (as per the Tory manifesto pledge) would increase public debt by the mid-2060s. “Taking back control comes with a whopping bill.”

The only way forward is to reject all forms of racism and xenophobia

It’s hardly surprising that anti-immigrant views are so widespread: media and governments in the capitalist countries have been systematically scapegoating immigrants for decades, and now the economic crisis has people fighting over scraps. That’s how xenophobia has become ‘populist’. The mainstream media consistently exaggerates the extent and the negative effects of immigration. Gary Younge points out that “three-quarters of Britons think immigration should be reduced. That’s hardly surprising. They think migrants comprise 31% of the UK’s population; the actual number is 13%. If you think something’s twice the size it really is, you’re bound to find it frightening.”

The purpose of this scapegoating and scaremongering is obvious enough: to distract people from the real reasons that things are getting worse. Karl Marx, analysing the “immigrant problem” in England around 150 years ago, painted a very vidid – and eerily familiar – picture:

Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker he regards himself as a member of the ruling nation and consequently he becomes a tool of the English aristocrats and capitalists against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself. He cherishes religious, social, and national prejudices against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the ‘poor whites’ to the Negroes in the former slave states of the USA. The Irishman pays him back with interest in his own money. He sees in the English worker both the accomplice and the stupid tool of the English rulers in Ireland.

This antagonism is artificially kept alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organisation. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power. And the latter is quite aware of this.

Racism and xenophobia create division, and division prevents the working class from waging effective class struggle – at a time when the ruling class is waging that class struggle relentlessly. As Tom O’Leary points out, “in the OECD economies the proportion of workers in part-time employment has risen from 5.4% in 1960 to over 20% in 2015. Union densities were 35.6% in 1975 and had fallen to less than half that, just 16.7% by 2014. It is not workers outside the advanced industrialised countries who have lowered wages in the G20 countries. It is the capitalist class in the G20 which has robbed workers of a greater proportion of the value they create”.

A Labour government will undoubtedly be a boost for all workers; it will demand more tax from the wealthy and invest it in public services, job creation and infrastructure. It can also be relied upon to be less awful than the Tories on the question of immigration. However, the Labour Party is still an arena for the fight against racism and xenophobia, as many of its high-profile MPs (including Tom Watson and Yvette Cooper) have joined the idiotic chorus demanding stricter immigration controls.

We should be struggling wholeheartedly against ruthless exploitation, against deregulation, against an economy that is absurdly skewed in favour of finance capital, against zero-hour contracts, against unemployment, against tax-dodging, for investment, for a living wage, for council housing, for more funding to the health and education services, against every form of oppression faced on a daily basis by workers. Division along the lines of race, religion or nationality weakens that struggle, and that is precisely its utility to the capitalist class. Without unity, we are consigned to a state of permanent defeat.

Towards a common ideology in the struggle against imperialism

This is an expanded version of a speech given by Carlos Martinez at the event ‘STRIKE THE EMPIRE BACK: legacies and examples of liberation from neo-colonialism and white supremacy’

As far as most people are concerned, ‘ideology’ is a term of abuse, an insult you fling around: we accuse people of being “too ideological”, of being bookworms, of dividing people with “isms and schisms”, of “thinking too much” (I have to say I’ve never in my life met anyone who actually thinks too much, but I’ve met plenty of people who don’t think enough!).

The Cult of Activism

There is this view that ideology divides us, that it gets in the way of working together, that it’s not really relevant, and that we need to focus purely on ‘action’, on practical activity, on campaigning. We don’t have need to inform our activism with analysis and understanding, we need to do like Nike: just do it. Pickets are good, placards are good, campaigns are good, petitions are good, demonstrations are good, fundraising is good, concerts are good; debate, books, history, study, analysis: not so much. Inasmuch as we need to occasionally need to spread ideas, we do it in cute 140-character slogans on Twitter, or Lord of the Rings memes on Instagram.

In part, this is a reaction to what’s called “ivory tower syndrome” – academics and intellectuals, sitting up in their ivory towers, writing beautiful words but having neither the intention nor the ability to put theory into practice. And even the beautiful ideas the generate are very flawed because they’re so divorced from reality and from the masses.

That is a genuine problem. However, as the saying goes, you don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. If I bite into an over-ripe strawberry and it tastes rotten, I don’t conclude from that experience that I’ll never eat a strawberry again. If there are ivory tower ideologues who are over-ripe and rotten, let’s ignore them and develop the ideology we need, the ideology that serves us.

The state of the movement

As it stands, we as a movement (inasmuch as there is a ‘movement’ – here I am using it as a general label for the various individuals and groups who oppose the status quo and who want to build an alternative) are quite active. There’s quite of lot of activism around, and yet, if we’re honest, we’re getting nowhere.

We’re no more united than we ever were – in fact we’re less united. We’re no more effective than we ever were – in fact we’re less effective. We have meetings, demonstrations, campaigns, pickets and so on, but almost never win anything, and we don’t really play to win; we’re just out there flying the flag.

And yet oppressed and working class people are under attack. In the course of the last three decades, the ruling class have managed to smash the majority of the unions and the community organisations. They’ve privatised everything. They’ve gone to war, killing our brothers and sisters in Yugoslavia, Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya in the hundreds of thousands. Benefits are cut, jobs disappear, wages are reduced, zero-hour contracts are introduced, bedroom taxes are introduced, banks are bailed out, student fees keep on rising, people are thrown in prison for protesting. Racism, xenophobia, sexism, homophobia are still prevalent with the dominant culture.

Meanwhile our political representation gets worse and worse, as the whole mainstream spectrum shifts to the right – as evidenced by UKIP’s success at the European election, and by the increasingly blurred lines between Tory and Labour politics.

As for the ruling class, the elite, the government, the police, the corporations, the 1% – they know what situation we’re in and therefore they know they can get away with pretty much anything they want. They know we are not in a position to fight the fight. That’s one of the main reasons we have whatever democratic rights we do have; that’s one of the main reasons they let us have the vote; that’s one of the main reasons they allow some level of freedom of speech: because they know full well we won’t use it to achieve anything meaningful.

Our ‘activism’ hasn’t prevented any of this. In some situations it’s even made it worse. To give a (thankfully) extreme example: when NATO was gearing up for its regime change operation against Libya, a sovereign African state, quite a few well-known activists thought the best thing to do would be to occupy Saif Gaddafi’s house in London, thereby totally playing into the mainstream agenda of demonising a state that the west was about to bomb into the stone age. What a situation, where you have courageous, passionate, righteous people – activists, people who are supposed to be on our side – and the media is able to play them like puppets!

Ideology is nothing to be scared of

If we don’t want to be played like puppets, we need ideology, we need understanding. It’s nothing to be afraid of. An ideology is simply a system of ideas – a set of beliefs, goals and strategies in relation to society. I think this scary word, ideology, can be summed up by three simple questions:

-

What is the current situation of society?

-

What changes do we want to achieve?

-

How do we go about creating those changes?

If you look around the world, and you look into history, you see that every movement that ever achieved anything meaningful is or was built on some kind of ideology. For example:

-

Malcolm X had an ideology, which one could argue was a mix of black nationalism, anti-imperialism, global south unity, socialism and pan-africanism, with Islam providing a moral-spiritual basis.

-

The Black Panthers had an ideology, based in Marxism, Maoism, black nationalism.

-

Closer to home, Sinn Fein and the IRA – who fought the British state to a stalemate (I wish we could do that!) – have an ideology, grounded in Irish nationalism, anti-imperialism and socialism.

-

The leaders of the Iranian revolution had and have an ideology, based in radical Islam, anti-imperialism, anti-zionism and orientation towards the poor. You can say something similar about Hezbollah, the only fighting force in the world to have defeated the Israeli army in battle (#JustSayin).

-

The liberation struggles in Vietnam, South Africa, Angola, Mozambique, Ghana, Kenya, Guinea Bissau, Zimbabwe, Palestine, Namibia, Algeria, Korea; the revolutions in Cuba, China, Russia, Grenada, Nicaragua: they all had/have an ideology, a system of ideas/beliefs/goals/strategies that people unite around.

These ideologies have plenty in common, particularly in terms of opposition to imperialism, opposition to colonialism, opposition to racism, and a general orientation in favour of the poor and marginalised. However, none of them are identical, and each reflects to some degree the history, traditions, culture and conditions of the people involved.

The President of the Cuban Parliament made an interesting self-criticism recently, when discussing the variations within the revolutionary process in Latin America:

“What characterises Latin America at the present moment is the fact that a number of countries, each in its own way, are constructing their own versions of socialism. For a long while now, one of the fundamental errors of socialist and revolutionary movements has been the belief that a socialist model exists. In reality, we should not be talking about socialism, but rather about socialisms in the plural. There is no socialism that is similar to another. As Mariátegui said, socialism is a ‘heroic creation’. If socialism is to be created, it must respond to realities, motivations, cultures, situations, contexts, all of which are objectives that are different from each other, not identical.”

There are theories that can point us in the right direction; there is history to learn from; but there’s no cookie-cutter that we can pick up to get rid of capitalism and imperialism.

What about us?

We too need an ideology. We need to work out a shared belief system, an agreed set of goals, an agreed set of strategies, that we can unite around and work together to create meaningful change. We need to answer those three questions: where are we at? Where do we need to be? How do we get there?

We will not agree on everything. There are a whole host of important issues that we have to be willing to agree to differ on. But I am convinced that there is space for a common platform.

Just look at the other side. The enemy has ideology. The elite, the rulers of society, the ultra-rich, the government, the state – they have an ideology. It’s imperialism and neoliberalism: the most brutal, the most harsh, the most ruthless form of capitalism, promoting nothing less than ‘freedom’ – total freedom for the rich to get ever richer.

Plus they’re so generous, they realise that the masses need an ideology too, so they create a ready-made ideology for us! The ideology they give us is: consumerism, individualism, diversions, divisions, racism, sexism, homophobia, selfies, twerking, porn, Call of Duty…

And we congratulate ourselves on all this freedom and democracy we’ve got! “It’s a free country”, we say. No! It’s not freedom, it’s not democracy. It’s bread and circuses. Give the masses cheap food and cheap entertainment, keep them divided, and you’ve got them under your control.

Minimum platform

What type of ideology do we need? Good question :-)

That’s the long conversation that we need to continue, in a spirit of inclusiveness, openness, comradeship, creativity and generosity. It’s going to take a while.

To me, in today’s world, perhaps the most relevant examples to look at can be found in Latin America, in particular in terms of the legacy of Hugo Chávez, may he rest in peace.

What does Chávez represent? The essence of ‘Chavismo’, I believe, is: 1) creative, non-dogmatic, up-to-date socialism; 2) consistent, militant anti-imperialism.

Socialism – there’s another scary word that isn’t really that scary. What is the socialism that is being pursued in Venezuela (and Cuba, and Nicaragua, and elsewhere)?

- Adopting policies that favour the poor: pursuing redistributive economics and social programmes that aim to permanently raise the status and living conditions of those at the bottom of society.

- Promoting the interests of the indigenous, the African, the worker, the woman. Protecting freedom of worship. Addressing discrimination on every dimension, in the interests of building unity and justice.

- Attempting to break the power of the old elite, the rich, the right, who have held society in their grip for so many centuries.

- Constructing a popular democracy, a state that is “for us, by us”.

As for Chávez’s legacy of anti-imperialism, that means consistently uniting with the widest possible forces against the main enemy. Chávez built solid, meaningful alliances with a very diverse range of states and movements, from Cuba to Brazil to China to Russia, Syria, Iran, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Belarus, Gaddafi’s Libya, Angola, DPR Korea, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Bolivia, and so on.

He wasn’t a gullible liberal or a radical fashionista; he didn’t disown his allies just because the western press was demonising them. He kept his eye on the prize of ending imperialist domination for once and for all and constructing a new, multipolar world where countries can develop in peace.

He always said that one should unite with anyone who had even the slightest chance of joining the fight against imperialism. I think that idea gives as a decent clue as to how we should move forward.