This article was also published by Telesur English on 21 December, 2019.

The UK parliamentary election of 12 December was a disaster for the working class and for oppressed communities; a defeat for the young, the elderly, people with disabilities, ethnic minorities, women, LGBT+ people, migrants and Muslims; a defeat for a planet that needs rescuing from climate catastrophe; a defeat for a world crying out for an end to imperialist warmongering and aggression.

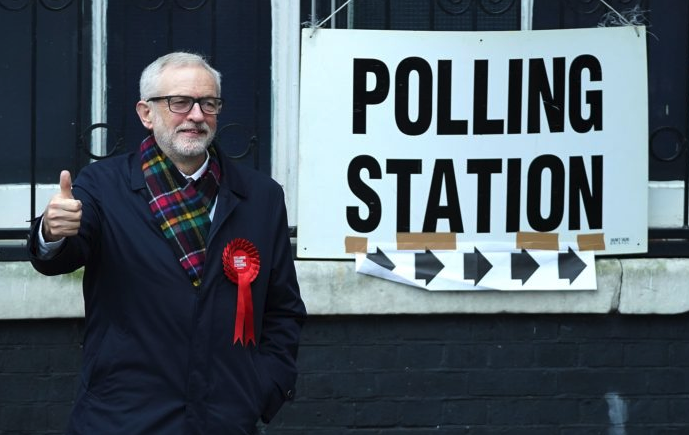

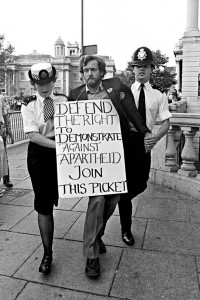

Labour went into the election with a powerful manifesto – a set of commitments that would have made life significantly better for millions of people, a platform from which to develop a peace-oriented multilateral foreign policy, a Green New Deal that could turn Britain into a trailblazer in the global fight against climate breakdown. Had Labour emerged victorious from the elections, the British government would have been led by some of the most consistent socialists in the country’s history; people who have fought against all types of discrimination and injustice their whole lives; people who taken the side of the oppressed and challenged the elite; people who have stood in solidarity with Palestine, Ireland, Cuba, Venezuela and Bolivia.

Tragically, Labour lost 60 seats and the Conservatives ended up with an overall majority of 80 seats (in spite of only having increased its vote share by 1.2 percent). This gives the Tories a commanding position from which to deepen austerity, deepen the racist ‘hostile environment’, form a comprehensive economic/political/military alignment with Trump’s US, and push through a neoliberal Brexit that impoverishes the many and enriches the few.

Did we go wrong over Brexit?

It’s only natural that Labour members and supporters now embark on a period of reflection and soul-searching. Why did we lose so badly, in spite of our great policies and in spite of how close we came to winning power at the last election in 2017? In spite of the energetic campaigning of thousands of activists around the country; in spite of ringing endorsements from the the likes of Stormzy, Akala, Brian Eno, Rob Delaney, Benjamin Zephaniah and Ronan Bennett?

One explanation that’s proving popular within the socialist left is that it was a fatal error to adopt a position of negotiating a new Brexit deal and then putting that to a referendum. The logic goes that, in 2017, we went into the election having promised to honour the results of the Brexit referendum, and we performed well. In 2019, we went into the election committed to a second referendum, and we did badly, ergo we should have stuck to our previous position on Brexit.

If only politics were so simple. The first rule of statistical analysis is that correlation isn’t causation. Labour’s Brexit policy changed and we performed poorly in the election, but there are many other moving parts to consider. We could just as factually state that in 2017 we went into the election without a commitment to free broadband, and we did well. In 2019, we had a policy of free broadband, and we did badly. Should we therefore deduce that our refusal to engage with voters’ concerns over fibre-optic technology was the cause of our defeat?

What’s true is that, although Labour lost far more votes to pro-Remain parties than pro-Leave parties, the bulk of the seats that were lost were in majority Leave-voting constituencies, particularly in the Midlands and the North. It’s possible that some of these could have been saved if we’d had a clearly pro-Brexit position, but only possible. We don’t know if voters would have supported a ‘Labour Brexit’ which sought to somewhat mitigate the racism and free market fundamentalism of the Tory Brexit project (albeit still pandering to xenophobia by seeking to end EU freedom of movement). The right-wing press would certainly have found ways to present this as a ‘sell-out’ and to insist that ‘Brexit means Brexit’. Then there’s the awkward fact that, even though the overall electorate in these constituencies voted to leave the EU, the majority of Labour voters favour remaining.

Plus it’s clear there were other factors in these constituencies’ desertion of Labour. Labour has been losing support in these areas for the best part of two decades, the result of general disillusionment with the status quo, the declining influence of trade unions (along with declining industries), some anaemic or downright reactionary MPs, ambivalent councils, a feeling that “Labour has taken us for granted for too long”, and a rising tide of xenophobic propaganda that has sought to blame immigrants for decaying living standards.

Another factor to consider is that there are dozens of marginals that could easily have been lost if Labour had a more pro-Brexit position, and indeed dozens of marginals that might have been won if Labour had a more anti-Brexit position. After all, for 28 percent of Labour voters, “stopping Brexit” was one of their top three reasons for voting Labour.

The polling trajectory throughout 2019 certainly doesn’t correspond with the hypothesis that Labour would have won the election had it adopted a more pro-Brexit position: from a high of 37 percent at the beginning of the year, Labour’s share went into decline as the original date for departing the EU – 29 March – approached. Labour received a pitiful 13 percent of the vote in the EU elections in May, and Labour’s general election polling reached its nadir of 25 percent during the period it was in talks with the Tories to try and reach some agreement over Brexit. Labour’s share started to increase after the party conference in September (at which the final position on Brexit was agreed) and then rose rapidly during the campaign, reaching 33 percent. This increase came specifically at the cost of the Liberal Democrats, whose vote share fell from 21 percent to 12 percent over the course of the campaign. Obviously this transfer of votes from Lib Dems to Labour wouldn’t have taken place if Labour had gone into the election with an unambiguously pro-Brexit stance.

Labour’s policy of negotiating a ‘soft’ Brexit deal (that retained Customs Union membership and protected workers’ rights) and subjecting that deal to a referendum was a mature and reasonable position for a party whose membership and voters are pro-Remain by a significant margin. In a situation where there are bitter divisions over Brexit throughout the Labour Party and the country as a whole, Labour’s position paved a road to unity and compromise. It took a damaging neoliberal Tory Brexit off the table, but it didn’t follow the flagrantly undemocratic Liberal Democrat pledge to scrap the original referendum altogether. Although the media tried to portray the policy as confusing and complicated, in reality it was perfectly simple, albeit without the vacuous soundbite quality of ‘Get Brexit Done’.

Not every battle is winnable. The election was called specifically to resolve the issue of Brexit, which is something that divides Labour’s support base and that doesn’t meaningfully divide the Tory support base. Boris Johnson used his first months in office to impose pro-Brexit message discipline on his MPs; he then called an election knowing full well that Labour’s support would be split, that Labour’s unifying policy hadn’t had long enough to gain broad support, and that the chillingly mendacious message of ‘Get Brexit Done’ would resonate with a significant part of the public that’s sick to the back teeth with endless parliamentary dilly-dallying. In that sense, Britain leaving the EU has acquired a symbolic power not unlike Donald Trump’s border wall.

Could Labour have won the election?

In these elections the ruling class employed a much more systematic and sophisticated approach to ensuring defeat for the Labour left. This approach had two main aspects: electoral strategy and media bias.

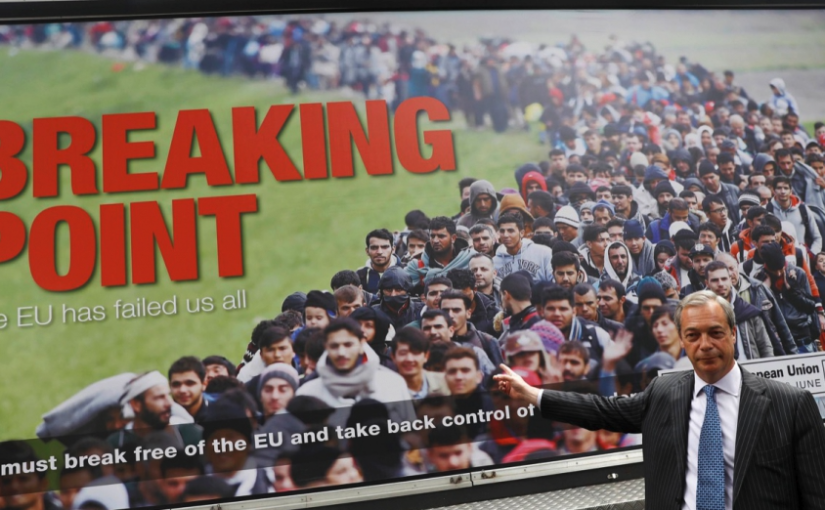

The success of the ruling class’s electoral strategy can be seen by the fact that the Tory vote only increased by 1.2 percent, but their share of parliamentary seats increased by 15 percent (from 317 to 365). Boris Johnson’s campaign team clearly targeted its energies and advertising spend in certain key constituencies. In this the Tories received enormous help from Nigel Farage, whose Brexit Party didn’t target any Conservative-held seats and instead focused on driving Labour’s vote down in marginals with a significant number of pro-Brexit Labour voters. The Brexit Party won a similar proportion of the vote to UKIP in 2017, but this time its strategy was carefully calculated to help secure a Boris Johnson majority, as instructed by Donald Trump.

Meanwhile the Lib Dems and Greens stood against Labour in lots of marginals, although the Lib Dems, Greens and Plaid Cymru agreed not to stand against each other in 60 seats. The first Labour loss announced on election night was Blyth Valley, where the Green vote of 1,146 was larger than the difference between the Tory and Labour votes. In Kensington, Emma Dent Coad – one of the best Labour MPs – was defeated by a margin of 150, with the Greens taking 535 votes and the Lib Dems running a very high profile campaign, again with the result of gifting the seat to the Tories.

It’s obviously the case that Jeremy Corbyn is unacceptable to a British ruling class that wants to continue austerity, that doesn’t want to see a meaningful redistribution of wealth, and that does want to continue fighting imperialist wars. That class identified Corbynism as an existential threat and, as the oldest and most experienced ruling class in history (albeit now showing signs of senile decay) went all out to stop it, using all the tricks in their book, their spooks, the right-wing press and the Chief Rabbi, not to mention the right wing of the Labour Party itself.

The media campaign against Corbyn was utterly vicious and relentless. In the words of the journalist and historian Mark Curtis, it “went far beyond anything against any previous Labour leader. It was surely the biggest propaganda campaign in UK history.” Shadow transport minister Andy McDonald stated that “never in my lifetime have I known any single individual so demonised and vilified, so grotesquely and so unfairly.” Corbyn was relentlessly slandered as an anti-semite and a ‘terrorist sympathiser’, constantly described as weak, wavering, vacillating, uncharismatic, unpatriotic. Unquestionably this hate campaign – which wasn’t by any means limited to the Tory press, but also reared its ugly head in the Guardian, the Independent and the New Statesman – had an impact.

Labour’s position certainly hasn’t been improved by the state of the parliamentary party, with so many MPs devoting the last four years to desperately trying to undermine Corbyn and oppose the shift to the left that has taken place under his leadership. This created a sense of chaos and disunity that was very easy for the media to leverage. This is very much the case in some Labour ‘heartlands’ seats like Barrow-in-Furness, where John Woodcock claimed that Corbyn “would pose a clear risk to UK national security as prime minister.” In Bassetlaw, John Mann – before resigning from the party and being made a baron – continuously called on Corbyn to step down. The outgoing MP for Dudley North, Ian Austin, called for a vote for the Tories. Needless to say, these three seats were all lost to the Tories.

In an election that was timed carefully to leverage ‘Brexit fatigue’, with a relentless propaganda campaign across the board, and with a hard-right Conservative Party that has been able to consolidate all public opinion from centre-right to all-out fascist, it was incredibly difficult for Labour to do well. We were up against the nexus of money and power, and the balance of forces didn’t allow us to break it.

Consolidating the left

All progressive opinion in this country has coalesced around the left Labour project led by Jeremy Corbyn. All reactionary opinion has coalesced around a hard right Conservative project inspired by Donald Trump.

Corbynism has put Labour back on the map as a meaningful political force, at a time when left-of-centre parties are in decline throughout most of Europe. The Corbyn leadership has uniquely combined a radical domestic economic policy with an internationalist, anti-war and anti-racist agenda. This agenda has proven hugely popular, as shown by the 2017 election results. The latest election is a significant setback, but that setback has taken place in specific circumstances that we need to understand.

Needless to say it hasn’t taken Tony Blair long to offer his opinion as to how Labour’s fortunes can be improved: “The takeover of the Labour party by the far left turned it into a glorified protest movement with cult trimmings, utterly incapable of being a credible government… Corbyn personified politically an idea, a brand, of quasi-revolutionary socialism, mixing far-left economic policy with deep hostility to western foreign policy. This never has appealed to traditional Labour voters, never will appeal to them, and represented for them a combination of misguided ideology and terminal ineptitude that they found insulting.”

Blair thinks that the situation demands a return to Blairism – quelle surprise. Yet this message won’t resonate with Labour’s membership, most of which joined the party after Corbyn’s emergence as front-runner for party leader in 2015. The problem with Blair’s take is that it’s a wilful misrepresentation of the facts. The policies of this “glorified protest movement” are both popular and credible. What kind of idiot wouldn’t support ending austerity, introducing a £10 per hour minimum wage, ending zero-hour contracts, reversing the privatisation of the NHS, nationalising water and energy, investing properly in healthcare and education, building hundreds of thousands of council homes, and creating hundreds of thousands of jobs in green energy and environmental conservation? To reverse Labour’s shift to the left in favour of pallid centrism would be to commit political suicide.

More insidious is the emerging ‘Blue Labour’ trend that is broadly accepting of an economic struggle against neoliberalism but that wants to push the party towards social conservatism and British nationalism. This narrative is exemplified by defeated Don Valley MP Caroline Flint’s complaint that the voters consider Jeremy Corbyn to be “too leftwing, unpatriotic, against the armed forces.” Blue Labour want to see the party drinking once more from Controls on Immigration mugs, rejecting internationalism, joyously waving the Union Jack and watching the Queen’s Christmas speech at 3pm on the dot.

This force says that Corbynism can’t win in the North and the Midlands because it’s too London-centric, too focused on ‘metropolitan’ values. This is a dog whistle. It means the Labour left is resolute in its fight against racism, xenophobia, sexism and homophobia; it means that Corbynism is internationalist and anti-war; it means that the current generation of Labour leadership isn’t willing to scapegoat immigrants, nor does it have fond feelings of nostalgia for the British Empire. It is precisely this profoundly important shift that has won Labour a wider support base than it has ever had, particularly among oppressed communities.

There’s been a loud chorus of voices, both on the left and right of the Labour Party, for Labour to reorient itself back to its ‘heartlands’ in the Midlands and North, for it to more specifically address the needs of the industrial (or post-industrial) working class outside the big cities. These workers are based in towns where manufacturing has largely collapsed and where reasonably well-paying and stable jobs in industry have been replaced by call centres, Amazon warehouses and Universal Credit. They’re often particularly susceptible to anti-immigration arguments because of the scarcity of dignified work (and often a lack of exposure to actual minority communities); that is, capitalist economics makes people more susceptible to capitalist propaganda. Many such towns have traditionally had relatively large numbers of young people in the armed forces (also related to the scarcity of dignified work), and therefore Jeremy Corbyn’s consistent opposition to Britain’s imperial adventures doesn’t go down well.

As history has shown time and time again, you don’t defeat backward ideas by pandering to them. In truth, Labour under Corbyn has already started to address the needs of these communities, most importantly pledging to end austerity, build council housing, reverse privatisation, invest in healthcare and education, and create hundreds of thousands of dignified jobs in the green energy sector. That platform represents a huge ‘reorientation’ to the needs of the entire working class. With time and patient work, and in an election that wasn’t fought almost exclusively over Brexit, that reorientation should win support. What Labour mustn’t do is to abandon those progressive parts of Corbynism that are supposedly toxic to the stereotyped Workington Man. Corbynism differs from ‘Old Labour’ specifically in its internationalism, in its opposition to wars, in its rejection of empire nostalgia, and in its consistent fight against racism, sexism and homophobia. This is what makes Labour in its current incarnation qualitatively different; this is what has mobilised the most progressive sections of the working class; this is what inspires people like Stormzy or Akala to vote for the first time in their lives. For those of us seeking to build a socialist, anti-racist and anti-imperialist mass movement, protecting and developing Corbynism is essential.

There are many thousands of people that campaigned for a Corbyn-led government, and millions of people that voted for it. We hoped we’d be able to fight for desperately-needed change with the help of a radical Labour government led by longstanding comrades of the left, anti-war, anti-austerity and anti-racist movements. That dream has died for the foreseeable future, but the struggle hasn’t; the main focus simply shifts back to the streets, communities and workplaces. What we’ve built is a radical movement of almost unprecedented scale in Britain: hundreds of thousands of people united around a platform that’s anti-neoliberal, anti-war, anti-racist and pro-planet. We must now engage in the campaigning, grassroots activism and political education we need to move forward. Consolidating this movement is the key question for now, as we prepare to resist a period of deep reaction.

The Tories have the parliamentary majority they require to deliver a hard Brexit and to comprehensively align Britain with US economic and military policy. There are massive fights ahead in relation to workers’ rights, protecting the planet, and resisting the racist divide and rule strategy that will inevitably accompany the general attack on the working class. Our movement must bounce back from the blow it’s suffered, and must put its experience and talents at the service of this struggle.