Fidel Castro Alejandro Ruz will be forever remembered as the pre-eminent leader of the Cuban Revolution; its chief strategist and charismatic comandante; a deeply principled, courageous, compassionate and intelligent human being; a guerrilla and a statesman; a relentless fighter against exploitation, oppression and injustice.

But we should be careful not to treat him as some kind of museum relic or historical curiosity. One can study the life of Genghis Khan for the sake of general interest, without expecting to harvest lessons with direct application to modern political life; however, Fidel operated in the current political era: the era of the transition from capitalism to socialism. Cuba was the first country in the western hemisphere to have a socialist revolution and to construct a new type of society. Cuba is the only country outside Southeast Asia to have kept its socialist system intact through the reverses of 1989-91. It has been, and remains, steadfast; a beacon of hope for progressive people worldwide; an example of how an oppressed people can break their chains and build a dignified life, even in the face of blockade and destabilisation orchestrated by the world’s foremost imperialist power – just the other side of the Straits of Florida.

The purpose of this article is to explore Fidel’s political legacy and highlight the aspects that are most relevant to continuing the project that he dedicated himself to: defeating capitalism and imperialism, and constructing in its place a new, socialist world based on the principles of solidarity, respect, equality and peace.

An unswerving revolutionary

In Highgate Cemetery, London, around 134 years ago, Frederick Engels described Karl Marx as being “before all else a revolutionist”, whose “real mission in life was to contribute, in one way or another, to the overthrow of capitalist society and of the state institutions which it had brought into being, to contribute to the liberation of the modern proletariat … Fighting was his element. And he fought with a passion, a tenacity and a success such as few could rival.”

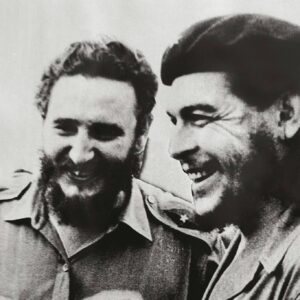

One could say something very similar about Fidel Castro: that he was an unswerving revolutionary; that he dedicated his long life to the pursuit of socialist revolution, to the overthrow of capitalism and imperialism, to the cause of freedom and national self-determination. He too fought with a passion, a tenacity and a success such as few could rival.

Capturing power in Cuba

The very existence of the Cuban socialism provides ample proof as to Fidel’s persistence, courage, imagination and strategic vision in pursuit of revolution. Nineteen-fifties Cuba was by no means an obvious place for socialism to blossom, given its geographic and cultural proximity to the US, the McCarthyite anti-communism that was prevalent at the time, and the enormous volumes of water separating it from any other socialist country. There was no revolutionary ‘model’ to follow: the Cuban Revolution didn’t develop directly out of the industrial centres like the October Revolution did; it didn’t grow out of a protracted people’s war like the Chinese Revolution; it didn’t take advantage of a post-war power vacuum such as had existed in Vietnam, Korea and Eastern/Central Europe. To even see an opening for revolution in Cuba at that time required great originality.

The very existence of the Cuban socialism provides ample proof as to Fidel’s persistence, courage, imagination and strategic vision in pursuit of revolution. Nineteen-fifties Cuba was by no means an obvious place for socialism to blossom, given its geographic and cultural proximity to the US, the McCarthyite anti-communism that was prevalent at the time, and the enormous volumes of water separating it from any other socialist country. There was no revolutionary ‘model’ to follow: the Cuban Revolution didn’t develop directly out of the industrial centres like the October Revolution did; it didn’t grow out of a protracted people’s war like the Chinese Revolution; it didn’t take advantage of a post-war power vacuum such as had existed in Vietnam, Korea and Eastern/Central Europe. To even see an opening for revolution in Cuba at that time required great originality.

A theme that runs through Fidel’s political life is that he had the knowledge and creativity to identify opportunities that few others would see, and the strength, courage, vision and skill to sieze those opportunities. Cuba’s Communist Party (then called the Popular Socialist Party) also saw the revolutionary potential of the moment, but it had no tangible plan for the capture of power. Fidel and his small group of guerrillas were unique in understanding that, in order to take advantage of the objective element (economic and political crisis, along with widespread popular discontent), it was necessary to apply the subjective element (in this case: conducting armed struggle in order to weaken the Batista regime to breaking point, whilst simultaneously providing a rallying point for the masses). Blas Roca, who was head of the PSP (and who would later become one of Fidel’s most trusted comrades), reflects on this question:

“We [the PSP] rightly foresaw, and greatly looked forward to, the prospect that in response to conditions created by the tyranny, the masses would organise and eventually engage in armed struggle or popular insurrection. But for a long time we failed to take any practical steps to hasten that prospect, because we believed that these struggles, including a prolonged general strike, would culminate in armed insurrection quite spontaneously. Hence, we did not prepare, did not organise or train armed detachments… That was our mistake. Fidel Castro’s historical merit is that he prepared, trained, and assembled the fighting elements needed to begin and carry on armed struggle as a means of destroying the tyranny.” (KS Karol, Guerrillas in Power)

Bay of Pigs

Fidel’s relentless pursuit of revolution was further evidenced during the Bay of Pigs invasion. In April 1961, only two years after the establishment of the revolutionary state, the CIA coordinated a large-scale military invasion of Cuba by exiles and mercenaries, backed by US Air Force bombers and transported by US Navy ships, with the objective of overthrowing Castro’s government. It is almost unimaginable that a small, isolated, newly-established state would be able to defend itself against the world’s most powerful military entity, but the Cuban government under Fidel’s leadership had anticipated this attack and was prepared for it.

The entire population was mobilised and trained; millions of people were under arms. The Cuban Air Force, although small, had been drilled in preparation for just this kind of invasion. Fidel personally coordinated the defence, which within 48 hours was able to capture the leaders of the invasion, sink a supply ship and achieve air superiority. Faced with defeat on the ground, embarrassment at the United Nations, and the threat of Soviet involvement on the side of Cuba (“The Soviet Union will render the Cuban people and their government all necessary help to repel an armed attack”), US President John F Kennedy was forced to withdraw support for the invasion, which promptly crumbled.

Survival in a post-Soviet world

The survival of Cuban socialism beyond the ‘end of history‘ era of the early 1990s is another extraordinary achievement that few people anticipated; another testament to the revolutionary spirit of the Cuban people and leadership. Cuba’s economy had been deeply integrated into the socialist world, with over 85% of its foreign trade being conducted through the CMEA (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, also known as Comecon, comprising the Soviet Union, the German Democratic Republic, Vietnam, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Romania, Mongolia, Poland and Hungary). The CMEA was disbanded in 1991. Of its member states, only Cuba and Vietnam resisted counter-revolution. Both faced major economic crises.

At this moment, Fidel and the leadership of the Cuban Communist Party could quite easily (and even understandably) have converted themselves into social democrats. They could have followed the path laid down by Gorbachev and abandoned their commitment to working class rule, to social justice, to political independence, to internationalism. They could have availed themselves of an IMF ‘bailout’, and before long they would have been accepted into the imperialist fold. Perhaps a few European heads of government might even have attended Fidel’s funeral (in the event, Alexis Tsipras of Greece was the only one). In the absence of a Cuban Yeltsin, the US would have been more than happy to work with a Cuban Gorbachev.

But Fidel understood from fairly early on that Gorbachev’s path was the road to ruin, commenting that “Perestroika is another man’s wife; I don’t want to get involved.” In his well-known and exceptionally powerful speech on 7 December 1989 in honour of the Cubans that gave their lives in the struggle to save Angola, Fidel made a clear denunciation of the Soviet Union’s programme of dismantling working class power, and made it plain that a parallel process would not be taking place in Cuba.

“In Cuba, we are engaged in a process of rectification. No revolution or truly socialist rectification is possible without a strong, disciplined, respected party. Such a process cannot be advanced by slandering socialism, destroying its values, casting slurs on the party, demoralising its vanguard, abandoning the party’s guiding role, eliminating social discipline and sowing chaos and anarchy everywhere. This may foster a counterrevolution, but not revolutionary changes.”

Continuing, he firmly re-stated Cuba’s commitment to socialism and willingness to be the global standard-bearer of the communist cause if necessary:

“We owe everything we are today to the revolution and to socialism. If Cuba were ever to return to capitalism, our independence and sovereignty would be lost forever; we would be an extension of Miami, a mere appendage of US imperialism; and the repugnant prediction that a US president made in the 19th century — when that country was considering the annexation of Cuba — that our island would fall into its hands like a ripe fruit, would prove true…

“We Cuban Communists and the millions of our people’s revolutionary soldiers will carry out the role assigned to us in history, not only as the first socialist state in the western hemisphere but also as staunch front-line defenders of the noble cause of all the destitute, exploited people in the world. We have never aspired to having custody of the banners and principles which the revolutionary movement has defended throughout its heroic and inspiring history. However, if fate were to decree that, one day, we would be among the last defenders of socialism in a world in which US imperialism had realised Hitler’s dreams of world domination, we would defend this bulwark to the last drop of our blood.”

When it became clear that Cuba wasn’t going to ride the wave of counter-revolution, the US decided to make things even more difficult by ramping up the economic blockade of the island. With the clouds of destitution and collapse looming ominously, the survival of Cuban socialism required incredible sacrifices and a creative overhaul of the national economy. Eighty percent of imports disappeared pretty much overnight, and many important goods were simply no longer available; the loss of fuel imports in particular meant that industry and transport were paralysed. Belts had to be tightened significantly in terms of food consumption and housing distribution; there was a renewed emphasis on tourism as a means of generating foreign exchange; small agricultural cooperatives and urban gardens sprang up with the government’s encouragement; car use was massively reduced (partly through the purchase of 1.2 million low-cost bicycles from China).

People had to get used to getting by with less, and the increase in foreign tourism brought complex new economic and social problems; however, the revolution survived. Socialism was preserved, Cuban independence was not put on the market, and nobody starved – even if many felt hunger pains for the first time. This survival would clearly not have been possible were it not for the level of revolutionary mobilisation of the Cuban people; if they did not feel passionately about defending the gains of the preceding three decades; if they weren’t willing to engage their energy and creative ingenuity for the sake of overcoming obstacles that must have appeared close to insurmountable. In this, they again had Fidel as their example and leader.

Yes, it is possible

Speaking at Fidel’s funeral, Raúl Castro gave an insightful and moving summary of his brother’s unique qualities; his blend of courage, creativity, foresight, knowledge, military/political acumen, energy, and ability to inspire.

“Fidel showed us that yes, it was possible to reach the coast of Cuba in the Granma yacht; that yes, it was possible to resist the enemy, hunger, rain and cold, and organise a revolutionary army in the Sierra Maestra; … that yes, it was possible to defeat, with the support of the entire people, the tyranny of Batista, backed by US imperialism… that yes, it was possible to defeat in 72 hours the mercenary invasion of Playa Girón and at the same time, continue the campaign to eradicate illiteracy in one year…

“That yes, it was possible to proclaim the socialist character of the Revolution 90 miles from the empire, and when its warships advanced toward Cuba, following the brigade of mercenary troops; that yes, it was possible to resolutely uphold the inalienable principles of our sovereignty, without fear of the threat of nuclear aggression by the United States in those days of the October 1962 missile crisis.

“That yes, it was possible to offer solidarity assistance to other sister peoples struggling against colonial oppression, external aggression and racism. That yes, it was possible to defeat the racist South Africans, saving Angola’s territorial integrity, forcing Namibia’s independence and delivering a harsh blow to the apartheid regime.

“That yes, it was possible to turn Cuba into a medical power, reduce infant mortality first, to the lowest rate in the Third World, then as compared with other rich countries; because at least on this continent our rate of infant mortality of children under one year of age is lower than Canada’s and the United States’, and at the same time, significantly increase the life expectancy of our population.

“That yes, it was possible to transform Cuba into a great scientific hub, advance in the modern and decisive fields of genetic engineering and biotechnology; insert ourselves within the fortress of international pharmaceuticals; develop tourism, despite the U.S. blockade; build causeways in the sea to make Cuba increasingly more attractive, obtaining greater monetary income from our natural charms.

“That yes, it is possible to resist, survive, and develop without renouncing our principles or the achievements won by socialism in a unipolar world dominated by the transnationals which emerged after the fall of the socialist camp in Europe and the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

“Fidel’s enduring lesson is that yes it is possible, that humans are able to overcome the harshest conditions as long as their willingness to triumph does not falter, they accurately assess every situation, and do not renounce their just and noble principles.”

An outstanding Marxist-Leninist

“Marxism taught me what society was. I was like a blindfolded man in a forest, who doesn’t even know where north or south is. If you don’t eventually come to truly understand the history of the class struggle, or at least have a clear idea that society is divided between the rich and the poor, and that some people subjugate and exploit other people, you’re lost in a forest, not knowing anything.” (Fidel Castro and Ignacio Ramonet: My Life – A Spoken Autobiography)

At a time when it’s not particularly fashionable to be a Marxist, a communist, it’s worth remembering that Fidel was exactly that. Some have tried to cast him as more of a Cuban nationalist or a stereotypical Latin American caudillo, but Fidel was of the consistent belief that “The future of mankind is the future of socialism and communism”; that “Marx was the greatest economic and political thinker of all times”.

The Cuban Revolution was, from the beginning, a socialist revolution; a process aimed at expropriating the capitalist class, foreign monopolies and landlords, and establishing working class rule. Fidel had become convinced of the correctness of Marxism-Leninism while at university in the late 1940s. “Toward the end of my university studies, I was no longer a utopian communist but rather an atypical communist who was acting independently. I based myself on a realistic analysis of our country’s situation… We were convinced Marxists and socialists… we had already read almost a whole library of the works of Marx, Engels, Lenin and other theoreticians.” (Speech at the inauguration of President Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, cited in the Fidel Castro Reader)

However, due to the widespread acceptance of McCarthyite propaganda, the terms ‘socialism’ and ‘Marxism’ weren’t often used until 1961. Fidel explains:

“Those were times of brutal anticommunism, the final years of McCarthyism, when by every possible means our powerful and imperial neighbour had tried to sow in the minds of our noble people all kinds of lies and prejudices. I would often meet an ordinary citizen and ask them a number of questions: whether they believed we should undertake land reform; whether it would be fair for families to own the homes for which at times they paid almost half their salaries. Also, if they believed that the people should own all the banks in order to use those resources to finance the development of the country. Whether those big factories – most of them foreign-owned – should belong to, and produce for, the people… things like that. I would ask 10, 15 similar questions and they would agree absolutely: ‘Yes, that would be great.’ In essence, if all those big stores and all those profitable businesses that now only enrich their privileged owners belonged to the people, and were used to enrich the people, would you agree? ‘Yes, yes,’ they would answer immediately. So, then I asked them: ‘Would you agree with socialism?’ Answer: ‘Socialism? No, no, no, not with socialism.’ Let alone communism… There was so much prejudice that this was an even more frightening word.” (ibid)

After three years of intense revolutionary activity following the capture of power – ending illiteracy, implementing land reform, setting up popular democratic structures, defending the revolution from invasion and destabilisation – the leadership decided to declare its ideological stance. By this point, the revolution had proven itself through actual socialist construction, and US ideological propaganda had lost much of its impact on the Cuban people. In a speech on 2 December 1961, broadcast on TV and radio, Fidel announced: “I am a Marxist-Leninist, and I shall be a Marxist-Leninist to the end of my life.”

Reflecting a few years later on McCarthyism and the saturation of anti-communism throughout the capitalist world, Fidel pointed out:

“The reactionary classes have always used every method to condemn and slander new ideas. Thus, all the paper and all the resources at their disposal are not sufficient to slander communist ideas; to slander the desire for a society in which human beings no longer exploit one another, but become real brothers and sisters; the dream of a society in which all human beings are truly equal in fact and in law – not simply in a constitutional clause as in some bourgeois constitutions which say that all men are born free and equal. Can all individuals be considered to be born free and equal in a society of exploiters and exploited, a society of rich and poor – where one child is born in a slum, in a humble cradle, and another child is born in a cradle of gold? How can it be said that these people have the same opportunities in life? The ancient dream of humankind – a dream that is possible today – of a society without exploiters or exploited, has aroused the hatred and rancor of all exploiters…

“The word ‘communist’ is not an insult but rather an honor for us… Within 100 years, there will be no greater glory, nothing more natural and rational, than to be called a communist. We are on the road toward a communist society. And if the imperialists don’t like it, they can lump it. From now on, gentlemen of UPI and AP, understand that when you call us ‘communists,’ you are giving us the greatest compliment you can give.” (Speech at the first central committee meeting of the newly-formed Communist Party of Cuba, 3 October 1965, cited in the Fidel Castro Reader)

Against dogmatism and revisionism

The twin curses of revisionism and dogmatism have clung to the left-wing movement with impressive tenacity over the years. ‘Revisionism’ means, essentially, stripping Marxism of its revolutionary objectives; reducing it to a slow reformism that doesn’t recognise the need to defeat the capitalist class. ‘Dogmatism’ means treating the works of Marx, Engels and Lenin (plus, variously, Trotsky, Stalin, Mao or whoever) as biblical sources of timeless and absolute truth, with universal application in all times and places; favouring the application of formulas and learned phrases over serious analysis of concrete conditions; and rejecting all forms of strategic compromise.

The Cuban Revolution came about at a time when the Soviet Union was elaborating an increasingly revisionist theory around its particular strategic needs (to peacefully rebuild and avoid further war), and the People’s Republic of China was reacting to this with an anti-revisionism which before long morphed into a rather dogmatic and unrealistic assessment of the global balance of forces. These differences fed into the Sino-Soviet split, which was to prove painfully destructive to the communist cause.

Fidel understood the potential danger that the Sino-Soviet split posed to the socialist camp and to progressive forces around the world; meanwhile he saw the impact of both revisionism and dogmatism within the Latin American left, and wanted to show that there was a different path.

“Due to the heterogeneity of this contemporary world, with different countries confronting dissimilar situations and most unequal levels of material, technical and cultural development, Marxism cannot be like a church, like a religious doctrine, with its Pope and ecumenical council. It is a revolutionary and dialectical doctrine, not a religious doctrine. It is a guide for revolutionary action, not a dogma. It is anti-Marxist to try to encapsulate Marxism in a sort of catechism. This diversity will inevitably lead to different interpretations… Marxism is a doctrine of revolutionaries, written by revolutionaries, developed by other revolutionaries, for revolutionaries. We will demonstrate our confidence in ourselves and our confidence in our ability to continue to develop our revolutionary path…

“We believe that revolutionary thought must take a new course; that we must leave behind old vices and sectarian positions of all kinds, including the positions of those who believe they have a monopoly on the revolution or on revolutionary theory. Poor theory! How it has suffered in these processes. Poor theory! How it has been abused, and is still being abused! All these years have taught us to meditate more and analyse better. We no longer accept any truths as ‘self-evident’. ‘Self-evident’ truths are a part of bourgeois philosophy. A whole series of old clichés should be abolished. Marxist, revolutionary political literature itself should be renewed, because if you simply repeat clichés, phraseology and verbiage that have been repeated for 35 years, you don’t win anyone over.” (Speech on 3 October 1965, op cit)

As discussed above, the Cubans didn’t try to model their revolution on anything that had come before. They didn’t attempt to apply some sort of Marxist template for building socialism; rather they combined their wide-ranging political and historical understanding with a deep analysis of prevailing conditions. The ideas with which they inspired the Cuban people were grounded in Marxism-Leninism but were also specifically Cuban. Fidel more than anyone understood the need to give Cuban socialism its own national flavour, which he successfully did by connecting the revolution with the Cuban (and wider Latin American) struggle for independence – tapping into an existing reverence for independence heroes such as José Martí and Antonio Maceo – and also the Cuban resistance movements against dictatorship and injustice in the 1930s and 40s.

In the first decade or so of the Cuban Revolution, it could perhaps be argued that, within the Latin American left, Cuba wanted to replace dogmatic adherence to the Soviet or Chinese models with dogmatic adherence to the Cuban model. The means by which the 26th of July movement captured power were promoted, and Cuba gave its support to rural guerrilla groups across the continent (“The only place where we didn’t try to promote revolution was Mexico”, Fidel noted), heavily criticising those leftist organisations that didn’t embrace guerrilla struggle.

The defeat of these attempts at revolution forced the Cubans to re-evaluate. In Cuba, Fidel and his comrades had benefitted from the element of surprise. By the time guerrilla struggles were launched elsewhere in Latin America, this element of surprise was gone, and the insurgents found that the CIA and its local allies were able to gain the upper hand through the use of advanced surveillance technology, air reconnaissance, psyops, propaganda, fostering disunity, and so on.

The victory of Salvador Allende in the Chilean presidential election of September 1970 represented the first time that an openly socialist government had come to power by constitutional means. Fidel was sufficiently inspired by, and curious about, Allende’s project that he toured Chile over the course of 25 days in late 1971 (a highly unusual amount of time for a head of state to spend visiting another country, especially given it was Fidel’s first trip to the South American mainland since 1959). As a result, he was able to make a serious study of the forces operating for and against the process. Speaking a couple of years later, in the wake of the Pinochet coup that brought the Popular Unity project to a tragic end, he sums up the Cuban leadership’s open mind regarding Allende’s Chilean path to socialism:

The victory of Salvador Allende in the Chilean presidential election of September 1970 represented the first time that an openly socialist government had come to power by constitutional means. Fidel was sufficiently inspired by, and curious about, Allende’s project that he toured Chile over the course of 25 days in late 1971 (a highly unusual amount of time for a head of state to spend visiting another country, especially given it was Fidel’s first trip to the South American mainland since 1959). As a result, he was able to make a serious study of the forces operating for and against the process. Speaking a couple of years later, in the wake of the Pinochet coup that brought the Popular Unity project to a tragic end, he sums up the Cuban leadership’s open mind regarding Allende’s Chilean path to socialism:

“President Allende and the Chilean revolutionary process awakened great interest and solidarity throughout the world. For the first time in history, a new experience was developed in Chile: the attempt to bring about the revolution by peaceful means, by legal means. And he was given the understanding and support of all the world in his effort – not only of the international Communist movement, but of very different political inclinations as well. We may say that that effort was appreciated even by those who weren’t Marxist-Leninists.

“And our party and people – in spite of the fact that we had made the revolution by other means – and all the other revolutionary peoples in the world supported him. We didn’t hesitate a minute, because we understood that there was a possibility in Chile of winning an electoral victory, in spite of all the resources of imperialism and the ruling classes, in spite of all the adverse circumstances. We didn’t hesitate in 1970 to publicly state our understanding and our support of the efforts which the Chilean left was making to win the elections that year.”

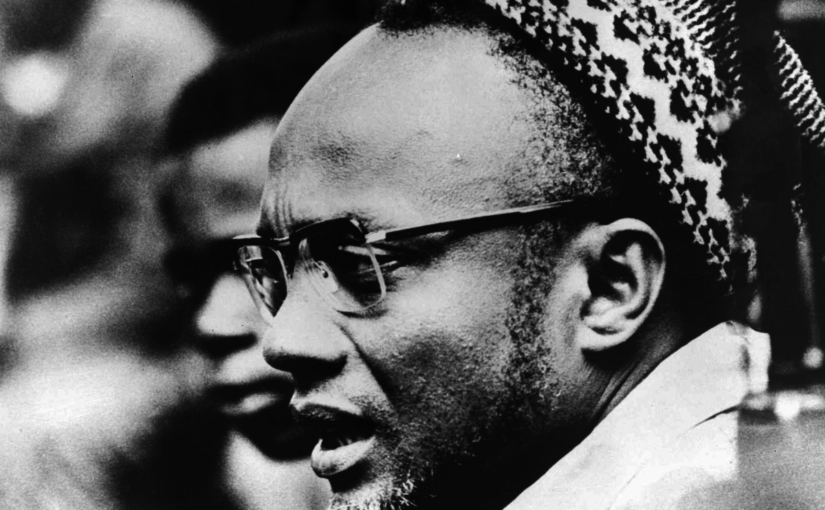

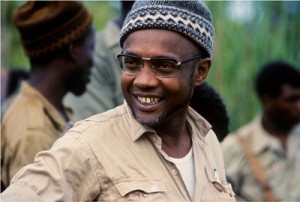

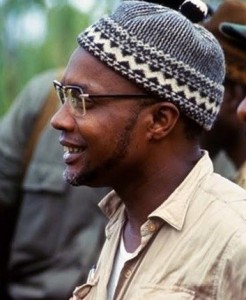

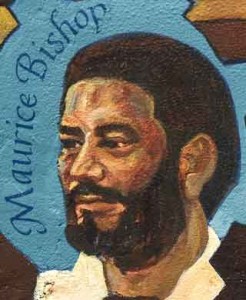

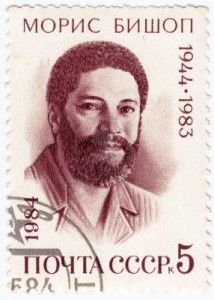

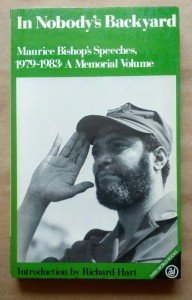

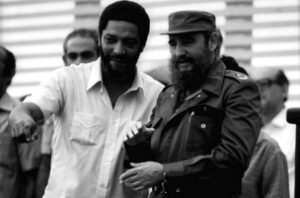

The end of the 1970s brought socialist forces to power in both Grenada and Nicaragua. The Grenadian revolutionaries, led by the brilliant and charismatic Maurice Bishop, came to power in a bloodless coup; meanwhile the Sandinistas in Nicaragua came to power on the basis of a guerrilla struggle that would have looked relatively familiar to their Cuban comrades. By now recognising the immense variety and specificity of revolutionary processes, Cuba gave an extraordinary level of fraternal support to Chile, Grenada and Nicaragua, whilst also giving some pertinent advice: that, in a regional context of near-total US domination, no revolutionary process can survive unless it protects itself with firm unity and militant self-defence (one can find a haunting tribute to this message in the last photo of Allende, facing Pinochet’s fascist CIA-backed coup on 11 September 1973, holding the AK-47 given to him personally by Fidel).

The end of the 1970s brought socialist forces to power in both Grenada and Nicaragua. The Grenadian revolutionaries, led by the brilliant and charismatic Maurice Bishop, came to power in a bloodless coup; meanwhile the Sandinistas in Nicaragua came to power on the basis of a guerrilla struggle that would have looked relatively familiar to their Cuban comrades. By now recognising the immense variety and specificity of revolutionary processes, Cuba gave an extraordinary level of fraternal support to Chile, Grenada and Nicaragua, whilst also giving some pertinent advice: that, in a regional context of near-total US domination, no revolutionary process can survive unless it protects itself with firm unity and militant self-defence (one can find a haunting tribute to this message in the last photo of Allende, facing Pinochet’s fascist CIA-backed coup on 11 September 1973, holding the AK-47 given to him personally by Fidel).

These experiences, in addition to the degeneration and demise of the Soviet Union, the unprecedented technological/military changes that have taken place in recent decades, plus the emergence of a raft of progressive governments in Latin America, have led the Cubans to a continually more advanced understanding of revolution and the different means of pursuing it. Ricardo Alarcón, President of the National Assembly of People’s Power from 1993 to 2013, sums up this learning well:

“What characterises Latin America at the present moment is the fact that a number of countries, each in its own way, are constructing their own versions of socialism. For a long while now, one of the fundamental errors of socialist and revolutionary movements has been the belief that a socialist model exists. In reality, we should not be talking about socialism, but rather about socialisms in the plural. There is no socialism that is similar to another. As Mariátegui said, socialism is a ‘heroic creation'”.

The link between 20th and 21st century socialism

The history of “actually existing socialism” thus far is sometimes considered in terms of two more-or-less distinct phases. The more recent one was famously labelled by its chief protagonist, Hugo Chávez, as “socialism of the 21st century” or “21st century socialism” (these constructions are the same in Spanish: socialismo del siglo 21); for the sake of a simple demarcation, the period starting with the October Revolution (1917) and ending with the dissolution of the Soviet Union (1991) is generally called “20th century socialism”.

Other than the incremental difference in the number of full centuries since the birth of Jesus, the conceptual contrast between the two phases is not entirely well-defined. However, if we define 21st century socialism on the basis of its history thus far, its characteristics seem to include: capturing (some) power via parliamentary elections; empowering workers and oppressed groups through social programmes, education, local democratic structures; moving towards a redistributive economic model whilst avoiding an all-out attack on capitalist economic power. Socialism of the 21st century has a clear, urgent focus on tackling neoliberalism, environmental destruction, and justice for indigenous, African and LBGTQ+ communities – problems that are more pressing and better understood than they were a few decades ago. In summary, it constitutes a pragmatic and creative approach to defending the needs of the oppressed in the modern era, in a context where more thorough revolutionary transformations (dismantling the capitalist state, expropriating the capitalist class, establishing a monopoly on power by the poor) aren’t realistically possible for the time being.

The status of Cuba – along with China, Vietnam, DPR Korea and Laos – in this distinction of “20th century socialism” and “21st century socialism” is a subject that deserves more attention. In terms of Fidel’s legacy as a Marxist-Leninist thinker and revolutionary, it’s worth noting that his influence spans both phases, and is a key link between them.

Fidel Castro at no point disavowed 20th century socialism. Not once did he imply that building a workers’ state (a “dictatorship of the proletariat”, to use Marx’s phrase for it) had been the wrong thing to do. He strongly believed that the European socialist countries had made a terrible, historic mistake in abandoning the socialist path and embracing capitalism. In a forceful speech given in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, in 1996, he said:

“There are many people in [the USSR and the former socialist countries in Europe] who vacillated, but who now are thinking, meditating. They see the disorder, lack of discipline and chaos, and they are perceiving that capitalism has no future. Only the countries which are persisting in socialism – in spite of the enormous difficulties resulting from us being left almost alone – using our intelligence, using our hearts, using our creative spirit, are capable of introducing innovations which will not only save socialism, but will improve it, and one day will bring it to a definitive triumph.

“Because of this, today, in these times, we can say: the future – and this can be said with more conviction than ever before – is one of socialism. Capitalism is in crisis, it does not have solutions to any of the world’s problems; only peoples such as those of Vietnam, Cuba and other countries, who did not abandon the principles of Marxism-Leninism, or of popular democratic government, or of the leadership of the Communist Party, are now forging ahead and achieving results not experienced by any other country in the world.”

Nonetheless, when a radical wave hit Latin America – with the election of, among others, Hugo Chávez in Venezuela (1999), Lula in Brazil (2002), Evo Morales in Bolivia (2005), Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua (2006) and Rafael Correa in Ecuador (2006) – Fidel embraced it with open arms, understanding that it represented an unprecedented step forward for the peoples of the continent and towards the Latin/Caribbean integration that Cuba had long pushed for. He understood that, with the US focus directed towards the Middle East, and with a certain strength in numbers, it was possible for this kind of project to succeed where Allende’s government had been defeated.

Nonetheless, when a radical wave hit Latin America – with the election of, among others, Hugo Chávez in Venezuela (1999), Lula in Brazil (2002), Evo Morales in Bolivia (2005), Daniel Ortega in Nicaragua (2006) and Rafael Correa in Ecuador (2006) – Fidel embraced it with open arms, understanding that it represented an unprecedented step forward for the peoples of the continent and towards the Latin/Caribbean integration that Cuba had long pushed for. He understood that, with the US focus directed towards the Middle East, and with a certain strength in numbers, it was possible for this kind of project to succeed where Allende’s government had been defeated.

Speaking at the inauguration ceremony of Hugo Chávez (to whom he was a longstanding friend and mentor), Fidel highlighted the immense significance of the election of a socialist in Venezuela: “Opportunities have often been lost, but you could not be forgiven if you lose this one.”

All the left-wing governments that have emerged in Latin America over the last 17 years have had enormous respect for Cuba and have sought the wisdom and guidance of its leadership. Like millions of people across the continent, they understand the extraordinary efforts Cuba has made to build and defend its revolution; to create the best education and healthcare systems in the Americas; to wipe out malnutrition and illiteracy; to make huge strides in eliminating racism, sexism and homophobia; to meaningfully tackle inequality; to send internationalist missions around the world; to establish Cuba as a centre of scientific innovation and environmental protection; and to achieve all this in the face of permanent hostility, threats and destabilisation coming from the US. No other country in Latin America can claim anywhere near such a level of success.

Not one of the left-wing governments in Latin America has sought to distance itself from Cuba on account of it not being ‘democratic’; they understand very well that it is far more democratic than the countries that slander it as a dictatorship (in terms of a government representing the will of its people, Cuba might well be the most democratic country in the world).

Through the strong bonds progressive Latin America has formed with Cuba – as well asnwith China – a clear thread of continuity has been established between 20th and 21st century socialism. The key differences are not ideological as such; rather they represent strategic differences corresponding to changed circumstances. Socialism of the 21st century will have a brighter future if, rather than rejecting the experiences of the socialist world so far, it considers itself the continuation of that project and leverages its vast experience. The most advanced contingents of 21st century socialism – specifically the PSUV (Socialist Unity Party of Venezuela), MAS (the Movement to Socialism in Bolivia), the FSLN (Sandinista Liberation Front of Nicaragua) and FMLN (Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front in El Salvador) – clearly do this. This is a valuable aspect of Fidel Castro’s legacy: understanding that the transition from capitalism to socialism is a single, global, multi-generational project with diverse problems, phases and strategies.

The consummate internationalist

“For the Cuban people internationalism is not merely a word but something that we have seen practised to the benefit of large sections of humankind.” (Nelson Mandela, Cuba, 26 July 1991)

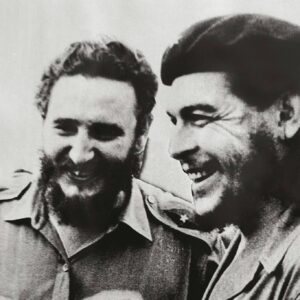

“Being internationalists is paying our debt to humanity. Those who are incapable of fighting for others will never be capable of fighting for themselves. And the heroism shown by our forces, by our people in other lands, faraway lands, must also serve to let the imperialists know what awaits them if one day they force us to fight on this land here.” (Fidel Castro, 1989, cited in Cuba and Angola: Fighting for Africa’s Freedom and Our Own)

Fidel Castro thought and operated on a global scale. He understood from the beginning that unity is strength; that socialist and anti-colonial states could not survive except through coordination and mutual support. He therefore pushed the Cuban Revolution to become the extraordinary example of revolutionary internationalism that it is.

His thinking was shaped early on by the extensive support given to Cuba by the Soviet Union, without which the Cuban Revolution simply would not have been able to hold out against the military, economic and political attacks of its neighbour to the north. Raúl Castro emphasises this point: “We must not forget another deep motivation [for our internationalism]. Cuba itself had already lived through the beautiful experience of the solidarity of other peoples, especially the people of the Soviet Union, who extended a friendly hand at crucial moments for the survival of the Cuban Revolution. The solidarity, support, and fraternal collaboration that the consistent practice of internationalism brought us at decisive moments created a sincere feeling, a consciousness of our debt to other peoples who might find themselves in similar circumstances.”

His thinking was shaped early on by the extensive support given to Cuba by the Soviet Union, without which the Cuban Revolution simply would not have been able to hold out against the military, economic and political attacks of its neighbour to the north. Raúl Castro emphasises this point: “We must not forget another deep motivation [for our internationalism]. Cuba itself had already lived through the beautiful experience of the solidarity of other peoples, especially the people of the Soviet Union, who extended a friendly hand at crucial moments for the survival of the Cuban Revolution. The solidarity, support, and fraternal collaboration that the consistent practice of internationalism brought us at decisive moments created a sincere feeling, a consciousness of our debt to other peoples who might find themselves in similar circumstances.”

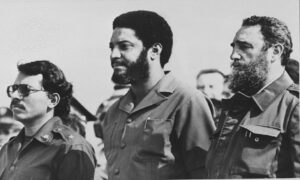

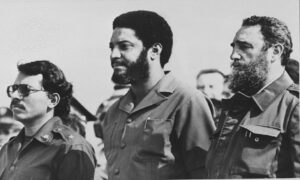

Cuban internationalism has become legendary, and has converted a small Caribbean island of 11 million people into one of the most respected countries on the planet. Speaking in relation to Cuba’s decisive contribution to the defeat of South African apartheid, the liberation of Namibia and the survival of Angola, Nelson Mandela commented: “The Cuban internationalists have made a contribution to African independence, freedom and justice unparalleled for its principled and selfless character… We in Africa are used to being victims of countries wanting to carve up our territory or subvert our sovereignty. It is unparalleled in African history to have another people rise to the defence of one of us.”

Aside from its support for Angola, Cuba also sent troops, advisers and health workers to support the liberation movements and revolutionary states in Guinea Bissau, Algeria, Guinea, Congo, Ethiopia, Western Sahara and South Yemen. Training and supplies were given to the heroic liberation movements in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Namibia, Mozambique and elsewhere. Hundreds of Cuban tank commanders came to Syria’s aid during the Yom Kippur War of 1973. Cuba gave abundant support to the revolutionary governments in Grenada (1979-83), Nicaragua (1979-90), Chile (1970-73) and to numerous liberation struggles around the South American continent.

It should be mentioned that Fidel didn’t delegate internationalism to others – he led by example. Indeed, he was the only foreign leader to visit the liberated zones of South Vietnam during the war. There were periods during the height of the struggle for Angola (1987-88) when Fidel devoted most of his time to giving strategic and tactical leadership to that fight; such was his dedication to the cause of ending colonialism and apartheid in Africa.

It should be mentioned that Fidel didn’t delegate internationalism to others – he led by example. Indeed, he was the only foreign leader to visit the liberated zones of South Vietnam during the war. There were periods during the height of the struggle for Angola (1987-88) when Fidel devoted most of his time to giving strategic and tactical leadership to that fight; such was his dedication to the cause of ending colonialism and apartheid in Africa.

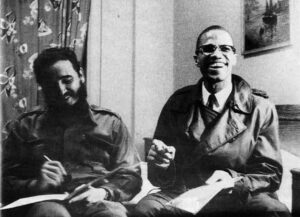

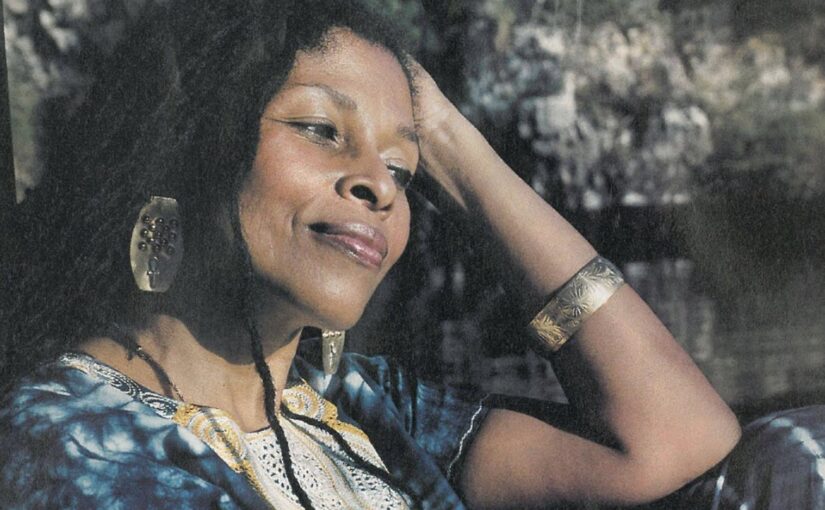

Havana has provided a home to many revolutionary exiles from the US, including Assata Shakur and Robert F Williams. Cuba has given unprecedented levels of medical support to West Africa, Haiti, Pakistan and many other places. At its Latin American School of Medicine it provides free or subsidised medical training for hundreds of African, Caribbean and Latin American students every year – even a handful of US students from poor families attend the school, on the condition that, on returning to the US, they use their training in the service of their communities. Fidel has been a consistent friend to the cause of Irish unity and self-determination.

As noted above, Cuba has been an inspiration for the wave of progressive governments in Latin America and has been central to the project of developing regional unity. The Second Declaration of Havana, 1962 captured the spirit of Latin American collective struggle long before it became an actual possibility: “No nation in Latin America is weak – because each forms part of a family of 200 million brothers and sisters, who suffer the same miseries, who harbour the same sentiments, who have the same enemy, who dream about the same better future and who count on the solidarity of all honest men and women throughout the world.”

Cuba has been, and remains, a vocal supporter of small countries struggling to maintain their independence and freedom in the face of imperialist pressure. That has included siding with several countries that have been more-or-less abandoned by the fashion-conscious western left, such as Syria, Libya, DPR Korea, Algeria, Zimbabwe and Belarus.

Fidel also recognised the importance of multipolarity as an important emerging trend in world politics, writing in one of his last essays that “the deep alliance of the peoples of the Russian Federation and China based on advanced science, strong army and the brave soldiers is capable of ensuring the survival of mankind”. He understood that, in a context where the US is desperately trying to maintain the uncontested hegemony it won after the fall of the Soviet Union, the establishment of alternative, non-imperialist world powers is a very promising development, creating a much more favourable space for other countries to follow a political and economic path that suits their own needs.

Man of the people

“The people, and the people alone, are the motive force in the making of world history.” (Mao Zedong)

Fidel had an extraordinary level of faith in the people, an insistence on people-centred government, and a profound understanding that the masses are the true makers of history. The revolution he led remains unsurpassed in its construction of a socialist morality that privileges social justice, fairness, equality, solidarity and participation.

Cuba is often maligned as a dictatorship, but such a label is hard to square with its record in practice of building socialist democracy. One of the first acts of the revolutionary government was to establish brigades of students willing to go out into the countryside in order to teach literacy to peasants who had been deprived even a basic education. Speaking at the United Nations General Assembly on 26 September 1960, Fidel described some of the first actions of his government:

“The revolution discovered over 10,000 teachers without a classroom, without work, and it immediately gave them jobs, because there were also half a million children who needed schools… What was yesterday a land without hope, a land of misery, a land of illiteracy, is gradually becoming one of the most enlightened, advanced and developed nations of this continent. The revolutionary government, in just 20 months, has created 10,000 new schools. In this brief period of time, we have doubled the number of rural schools that had been established in 50 years, and Cuba today is the first country of the Americas that has met all its educational needs, having teachers in even the most remote corners of the mountains. In this brief period of time, the revolutionary government has built 25,000 houses in the countryside and the urban areas… Cuba will be the first country in the Americas that, after a few months, will be able to say it does not have a single illiterate person in the country.”

A ruthless, exploitative dictatorship has no need to provide education to people that have never had education. Growing sugar cane for export does not demand a familiarity with the works of José Martí, Cervantes and so on. The only motivation of the Cuban government in setting up such a programme was to improve the lives of ordinary people, and to empower them to participate more actively in running their society, in making history. Cuba continues to have an education system that is the envy of the world – and which is free at every level.

A ruthless, exploitative dictatorship will exacerbate and leverage racial and gender divisions in order to keep people divided and ruled. And yet the Cuban government has made remarkable progress in tackling discrimination and inequality, and promoting unity. As Isaac Saney writes in his excellent book ‘Cuba – A Revolution in Motion’: “It can be argued that Cuba has done more than any other country to dismantle institutionalised racism and generate racial harmony.”

From the beginning, Fidel saw racism as a major obstacle to the revolution; he considered that a better society could only built with “a united revolutionary people, whose consciousness is constantly developing and whose unity is indestructible” (speech given on the centenary of Cuba’s first declaration of independence, 10 October 1968). Racism was systemic in pre-revolutionary Cuba, with a system of racial segregation in place that would have brought a contented smile to the faces of the architects of South African apartheid. Fidel appreciated that, even with the defeat of the reactionary classes that benefited from racism, it wouldn’t simply die out of its own accord. In a speech on 21 March 1959 – just a couple of months after the capture of power – he made a profound point:

From the beginning, Fidel saw racism as a major obstacle to the revolution; he considered that a better society could only built with “a united revolutionary people, whose consciousness is constantly developing and whose unity is indestructible” (speech given on the centenary of Cuba’s first declaration of independence, 10 October 1968). Racism was systemic in pre-revolutionary Cuba, with a system of racial segregation in place that would have brought a contented smile to the faces of the architects of South African apartheid. Fidel appreciated that, even with the defeat of the reactionary classes that benefited from racism, it wouldn’t simply die out of its own accord. In a speech on 21 March 1959 – just a couple of months after the capture of power – he made a profound point:

“In all fairness, I must say that it is not only the aristocracy who practise discrimination. There are very humble people who also discriminate. There are workers who hold the same prejudices as any wealthy person, and this is what is most absurd and sad and should compel people to meditate on the problem. Why do we not tackle this problem radically and with love, not in a spirit of division and hate? Why not educate and destroy the prejudice of centuries, the prejudice handed down to us from such an odious institution as slavery?”

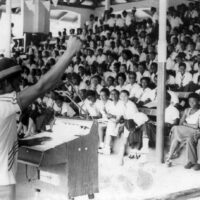

Displaying an outstanding humanity and depth of historical understanding, Fidel also connected the struggle against racism in Cuba with the centuries-old colonial domination of Africa, and in turn with the global struggle against colonialism, imperialism and apartheid. At a mass rally of over a million people in Havana in December 1975, where he explains the reasons for Cuba’s solidarity with Angola, he affirmed:

“African blood flows freely through our veins. Many of our ancestors came from Africa to this land. As slaves they struggled a great deal. They fought as members of the Liberating Army of Cuba. We’re brothers and sisters of the people of Africa and we’re ready to fight on their behalf.

“Racial discrimination existed in our country. Is there anyone who doesn’t know this, who doesn’t remember it? Many public parks had separate walks for blacks and for whites. Is there anyone who doesn’t recall that African descendants were barred from many places, from recreation centres and schools? Is there anyone who has forgotten that racial discrimination was prevalent in all aspects of work and study?

“And today, who are the representatives, the symbols of the most hateful and inhuman form of racial discrimination? The South African fascists and racists. And Yankee imperialism, without scruples of any kind, has launched South African mercenary troops in an attempt to crush Angola’s independence and is now outraged by our help to Angola, our support for Africa and our defence of Africa.

“In keeping with the duties rooted in our principles, our ideology, our convictions and our very own blood, we shall defend Angola and Africa! And when we say defend, we mean it in the strict sense of the word. And when we say struggle, we mean it also in the strict sense of the word. Let the South African racists and the Yankee imperialists be warned. We are part of the world revolutionary movement, and in Africa’s struggle against racists and imperialists, we’ll stand, without any hesitation, side by side with the peoples of Africa.”

What has been built in Cuba – through education, through struggle against discrimination, through the establishment of political structures such as the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution – is a genuine people’s democracy; a government that relies on mass participation and that derives its legitimacy entirely through its efforts to represent the interests of the people.

What has been built in Cuba – through education, through struggle against discrimination, through the establishment of political structures such as the Committees for the Defence of the Revolution – is a genuine people’s democracy; a government that relies on mass participation and that derives its legitimacy entirely through its efforts to represent the interests of the people.

Cuba doesn’t conform to the western liberal concept of democracy, for the simple reason that it has developed a political structure that is better suited to the people’s needs; which is in fact more democratic. In western parliamentary democracy, the masses have the right to say what they think (a right that is usually respected), and the government has the right to completely ignore them (a right that is almost always respected). For example, the recent constitutional changes and associated economic reforms in Cuba were shaped through a process of debate and consultation lasting four years and involving practically the entire population. This was a huge exercise in democracy that stands in stark contrast to the way in which austerity has been rolled out in Europe.

In Cuba there is only one political party – the Cuban Communist Party – but this reflects the fact that this party represents the needs of the ruling classes in Cuban society: the working class and peasantry. And within that party there is a massive variety of opinions on every matter under the sun. The only political question on which unanimity is expected is that of moving forward with socialism, rather than capitulating to imperialist pressure and returning to capitalism. What reasonable person would argue with that? Cuba returning to capitalism would be like France returning to feudalism, South Africa returning to apartheid, the US returning to slavery. As ever, Fidel puts it well:

“Within the revolution, everything; against the revolution, nothing. Against the revolution, nothing, because the revolution also has its rights, and the first right of the revolution is the right to exist, and no one can oppose the revolution’s right to exist. Inasmuch as the revolution embodies the interests of the people, inasmuch as the revolution symbolises the interests of the whole nation, no one can justly claim a right to oppose it.”

Living up to Fidel’s legacy

As Nicaraguan revolutionary Tomás Borge said about his comrade Carlos Fonseca, Fidel is “among the dead that never die.” His life as a revolutionary, a Marxist-Leninist, an internationalist, an outstanding and compassionate builder of a new society, now becomes the collective property of the progressive millions of the world: the anti-imperialists, the socialists, the communists. The only condition of ownership is that we use it to help us move humankind further along the path towards a world without war, oppression, discrimination, exploitation, domination and prejudice; a world that protects the earth, which restores community, and which creates conditions for every single human being – of this and future generations – to be able to enjoy a dignified, fulfilling, healthy, interesting and happy life.