The recent presidential elections in Brazil, which saw the re-election of Dilma Rousseff in a tightly-fought second-round contest against Aécio Neves of the Social Democratic Party (PSDB), were accompanied by an extended hostile media campaign directed at the Workers Party (PT) government. Loud criticism has come from both ends of the political spectrum. Apparently, this Brazilian government is at once ‘neoliberal’ and ‘communist’; it panders to the elite and it panders to the masses; it squeezes the rich and the poor; it’s part of a conspiracy both with and against the United States; it’s “sold out” to both China and the IMF; its programmes of poverty alleviation are simultaneously ‘irresponsible’ and ‘inadequate’; it attacks trade unions whilst at the same time allowing them to render the economy uncompetitive; it reminds some of the bad old days of the dictatorship, while it makes others miss the good old days of the dictatorship.

With the exception perhaps of the Brazilian electorate, one might be forgiven for thinking that nobody likes the PT very much.

It’s relatively easy to understand the position of the Brazilian elite and the national news media over which they hold a virtual monopoly. They look at the former Marxist guerrilla Dilma Rousseff, who served time in prison for her role in the underground struggle against Brazil’s 1964-85 military dictatorship, and they see the International Communist Conspiracy. They despise the fact that the government wastes so much money on ending extreme poverty and illiteracy; they despise the fact that so many government members have close links with trade unions and/or were part of the armed resistance to the dictatorship; they detest the government’s use of affirmative action policies to try and resolve the abhorrent racial injustice that endures from centuries of slavery.

The PT’s founder and guiding figure, Luiz Inácio ‘Lula’ da Silva, comes in for special vitriol, as a man without a university education; an uppity peasant-turned-strike-leader from the Northeast; an untouchable who sold peanuts by the roadside as a child to supplement the family’s income; a bearded, uncouth oaf who speaks with a working class accent and has none of the slickness of respectable bourgeois politicians (there are vicious rumours circulating that he doesn’t even put Brylcreem in his hair).

The position of the western left is a little less easy to understand. This group tends to look upon the PT government with a certain sense of disappointment. The many European “revolutionaries without a revolution” (as Emir Sader rather unkindly but painfully accurately describes them) were clearly hoping that Lula and his comrades would be able to wave the magic wand bequeathed to the world by Lenin and that Brazil would be transformed in an instant from one of the most unequal societies on the planet into a socialist paradise. When it appeared that Lula – a working class man from the most humble Nordeste background – couldn’t read the instruction manual to the magic wand, many became disillusioned. Tariq Ali, for example, described the PT as “the big disappointment” of the Latin American left, and claims that “the PT administration, frightened of its own shadow, remains mired in the IMF swamp.” He even went so far as to say that Lula was “a weak leader who is so excited at being in power, that he forgets why he is”.

When large protests erupted in Brazil last year, both the mainstream press and much of the left press went into overdrive with denunciations of a supposedly anti-popular Brazilian government. The aim of the right was clear enough: to stoke popular disatisfaction to such a degree that the PT would lose the elections.

“The ruling class, the capitalists, those who represent US imperialist interests and their ideological spokespeople, who appear on television every day, have one big goal: Wear down the Dilma government. Weaken the organizations of the working class, defeat any proposed structural changes in Brazilian society and win the 2014 elections to restore full rightist hegemony in command of the Brazilian state, which is now under dispute.”

It was all too predictable that the ultra-left would be brought into this project. Emir Sader writes:

“The progressive governments of the continent (Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Ecuador, Venezuela, Bolivia) are victims of massive campaigns driven by forces of the international right, and several European voices echo these campaigns… People of the left itself, including the more radical left, reproduce these narratives, doing the work of the international right against these progressive governments.”

This is nothing new. Such a heart-warming de facto unity of the right and ultra-left can be found the world over, from Brazil to South Africa, from Syria to Venezuela. However, in the context of such a concerted critique of the PT government, it’s important to take a detailed look into the history and trajectory of that government, and furthermore to explore ideas around how the PT’s strategy fits into a longer-term movement in pursuit of socialism.

The record in power of the PT

Poverty, inequality and discrimination

Brazil is, and has for centuries been, one of the most unequal countries in the world. While the (almost exclusively white) inhabitants of affluent Rio and São Paulo suburbs fly in and out of their gated communities in helicopters, tens of millions of (predominantly black, indigenous and mixed) workers and peasants live in slums and villages with extremely limited access to education, employment and basic services. The basic economic structure of colonial times remains more-or-less intact in large parts of the country. Land ownership is still dominated by a few latifundistas, and there are many areas where something akin to slave labour is still in force. At least until the 90s, the export economy – built on the back of the most extensive and longest-lasting system of slavery in the Americas – benefitted the oligarchs alone.

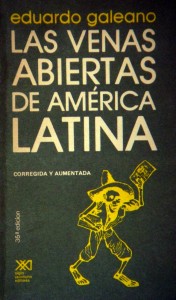

In his classic 1971 work, Open Veins of Latin America, Eduardo Galeano describes the levels of intense poverty and inhumanity prevailing in Brazil:

In his classic 1971 work, Open Veins of Latin America, Eduardo Galeano describes the levels of intense poverty and inhumanity prevailing in Brazil:

The Brazilian Northeast is today the most underdeveloped area in the Western hemisphere. As a result of sugar monoculture it is a concentration camp for 30 million people — on the same soil that produced the most lucrative business of the colonial agricultural economy in Latin America… In large areas the owner’s or administrator’s ‘right of the first night’ for each girl is still effective. A third of Recife’s population lives in miserable hovels; in one district, Casa Amarela, more than half the babies die before they are a year old. Child prostitution — girls of ten or twelve sold by their parents — is common in Northeastern cities. Some plantations pay less for a day’s work than the lowest wage in India.

Galeano remarks on how Brazil’s subject status within the global economy perpetuates the intense poverty of the producers:

To keep their chocolate cheap, the big cacao consumers — the United States, Britain, West Germany, Holland, France — stimulate competition between African cacao and cacao from Brazil and Ecuador. Controlling prices as they do, these nations bring on periods of depression which put cacao workers back on the road. The unemployed look for trees to sleep under and green bananas to fool their stomachs: one product they certainly don’t eat is the fine chocolate that Brazil actually imports from France and Switzerland. Chocolate costs more and more; cacao less and less.

Under the military dictatorship of 1964-85, there was a major industrialisation drive; numerous industries were built up; an entire capital city (Brasilia) was created; and fortunes were made for some big Brazilian families and their foreign backers. However, industrialisation in itself is not a panacea; it is a necessary but not sufficient condition for creating a prosperous and modern society. The dictatorship’s version of development was to open Brazil up to maximum exploitation by Europe and the US, creating wealth that dismally failed to ‘trickle down’. It was an early neoliberal experiment that ran parallel to the violent free-market fundamentalism of Pinochet’s Chile. “The concentration of income that accompanied this growth was marked, a direct result of the regime’s early, and crude, version of ‘Reaganomics’: 75 per cent of the increase in Brazilian income between 1964 and 1974 was appropriated by the richest 10 per cent of the population, while the poorest half took in only 10 per cent.” (Emir Sader and Ken Silverstein, ‘Without Fear of Being Happy’, 1991)

Even relying on the dictatorship’s statistics, by the early 80s, “around 70 percent of the population had less than the minimum daily calorie intake necessary for human development, and around seventy-one million were defined as undernourished.” (Richard Bourne, ‘Lula of Brazil’, 2009)

Writing in 2003, shortly after Lula’s first election victory, Australian travel writer Peter Robb vividly describes a country not much different from that depicted by Eduardo Galeano thirty years earlier:

Writing in 2003, shortly after Lula’s first election victory, Australian travel writer Peter Robb vividly describes a country not much different from that depicted by Eduardo Galeano thirty years earlier:

The gap between rich and poor was more than six times the difference in countries like India, Egypt, Pakistan, Indonesia. It was more than double the wealth gap in Russia, Mexico, Nigeria. Double the gap in Chile, Venezuela, Colombia too — the only Latin American country that came anywhere close to Brazil’s inequalities was Guatemala. Brazil’s wealth gap was more than six times Japan’s or Germany’s, four times Canada’s, more than three times the differences in Britain, the United States or Australia…

In Brazil, the street children seemed to number in the millions, and they had no real ties to the adult world at all. Recife teemed with skeletal child glue sniffers. They were the bottom layer of a whole heap of Brazilian children abandoned by the society they were born into, a society whose violence in home and neighborhood made them take their chance on the streets as the lesser evil.

Steps towards a solution

Such was the situation Lula and his government inherited in 2003; such was the extent of the problem they had been elected to fix. The commitment to eradicating extreme poverty has been the defining feature of successive PT administrations over the past 12 years; and, more than anything, it has differentiated the PT-led government from the governments that came before it. The Bolsa Família welfare programme, which benefits around 50 million people, has become “a worldwide reference – an example of how to fight poverty… Such is the fascination of Bolsa-Família that Brazil is now being consulted for advice on income transfer programmes by countries across Africa, the Middle East and Asia.” Brazil is described by the UN World Food Program as “a world champion in the fight against hunger”.

An important document by Mark Weisbrot, Jake Johnston, and Stephan Lefebvre, entitled The Brazilian Economy in Transition: Macroeconomic Policy, Labor and Inequality, analyses very thoroughly the data on poverty and inequality, and it’s worth quoting from at length:

An important document by Mark Weisbrot, Jake Johnston, and Stephan Lefebvre, entitled The Brazilian Economy in Transition: Macroeconomic Policy, Labor and Inequality, analyses very thoroughly the data on poverty and inequality, and it’s worth quoting from at length:

Since the Workers’ Party came to power with President Lula taking office in 2003, poverty has been reduced by over 55 percent, from 35.8 percent of the population to 15.9 percent in 2012. Extreme poverty has been reduced by 65 percent, from 15.2 percent to 5.3 percent over the same time period. Over the last decade, 31.5 million Brazilians were lifted out of poverty and, of that number, over 16 million out of extreme poverty.

From 2003 to 2012 the number of people covered by Bolsa Familia benefits increased from 16.2 million to 57.8 million. As a percent of the population, coverage increased from below 9 percent in 2003 to nearly 29 percent in 2012.

Both unemployment and informality – the percentage of workers in the informal sector – have decreased considerably over the past decade. Unemployment peaked at 13.0 percent in 2003 and has declined pretty steadily, except for some temporary upticks during recession, to 5.0 percent today – a historic low.

The percentage of workers employed in the informal sector has fallen sharply from 22.5 in December 2003 to 13.3 percent in August 2014. This shift toward formal sector employment is important for protections such as pensions, sickness and disability benefits, paid annual leave, and regulation of working hours.

For 2003-2014, the real minimum wage increased in Brazil by 76.2 percent. This was a major contributor to the decline in inequality over the past decade.

While Brazil remains an extremely unequal country in terms of income distribution, since 2003, the Gini coefficient has also been reduced. After remaining nearly constant for the decade prior, beginning in 2003, the Gini has fallen from 0.59 to 0.53.

During this period, the income of the poorest 20 percent increased at a rate seven times that of the richest 20 percent. According to the current trajectory, extreme poverty will be completely wiped out within the next few years – this is largely a matter of reaching out to poor families in the most remote areas. Referring to the estimated 700,000 Brazilians still suffering extreme poverty, President Rousseff says: “We must find them. The state should not wait for them to come knocking on our door.” This is echoed by the minister for social development, Tereza Campello: “We need to change the mindset that it is up to a poor person to come to the state, and ensure that the state reaches out to the poor person.” Rather different to the government attitude in, say, Britain or the US.

While the international mainstream media outlets have little interest in such trivia as employment, poverty, education, healthcare, life expectancy and the like (their concern for the wellbeing of the Brazilian masses only manifests itself when it comes to spitting venom in relation to bus fare increases in Rio), the impact of the PT’s policies on the most humble sectors of the population is vast and unprecedented.

“‘This is the first government to pay any attention to us, and before they did we could really go hungry out here,’ said Mr. Francisco, a wiry 47-year-old … who lives with his small family on a dusty plot outside the town of Paulistana in Piauí state. Illiterate himself, he sent his son to school thanks to Bolsa Familia payments… He lived the first 35 years of his life without electricity. Now his home is connected to the grid under a program called ‘Light for All.’”

The lifting out of poverty of over 30 million people is a frankly extraordinary achievement, and should frame the debate over the strengths and weaknesses of the PT administrations. While huge social, economic and political problems persist – and a capitalist economic system remains firmly in place – it is crucial to recognise the historic nature of the changes that have taken place.

In the same time period (2003 to now), Brazil’s infant mortality rate has been drastically reduced: from 58 deaths per every 1,000 live births (one of the highest in the world) to 16 deaths per every 1,000 live births. The government’s AIDS prevention programmes “have kept AIDS from being an epidemic for millions of Brazilians. Brazil is recognized internationally as a leader in AIDS prevention and treatment programs that are available absolutely free to anyone who needs them.” The Mais Médicos initiative has seen several thousand Cuban doctors deployed to urban slums and poverty-stricken rural villages that previously had no resident doctors. Their arrival “has been welcomed as a godsend … in the poorest corners of Brazil”. What’s more, it provides much-needed foreign currency for Cuba and promotes the blossoming Brazil-Cuba relationship.

Wide-ranging efforts are being made to end modern slavery: Caio Magri writes that “Brazilian efforts to eradicate slave labor are considered an international reference”. Each year, the government’s anti-slavery task force frees thousands of debt slaves who have been trapped into a life of producing charcoal, “cutting sugar cane or clearing tracts of Amazon rainforest for cattle ranchers. Housed in isolated and often squalid jungle camps, they are forced to work until they have paid off debts for food, medicine and housing.”

Wide-ranging efforts are being made to end modern slavery: Caio Magri writes that “Brazilian efforts to eradicate slave labor are considered an international reference”. Each year, the government’s anti-slavery task force frees thousands of debt slaves who have been trapped into a life of producing charcoal, “cutting sugar cane or clearing tracts of Amazon rainforest for cattle ranchers. Housed in isolated and often squalid jungle camps, they are forced to work until they have paid off debts for food, medicine and housing.”

Public expenditure on education increased from $17bn in 2002 to $94bn in 2012, and will increase even more as a result of the Oil Royalties Bill that was passed in response to the large student-led demonstrations of 2013. This bill stipulates that 75% of oil profits derived by the Brazilian government will be apportioned to education (with the remaining 25% going into the health system). The result of this focus on education is that more children are attending school; they are spending longer in school on average (“The average years each Brazilian spends in school is now increasing at a rate of almost two years of study per decade.”); more are heading on to university; and there is vastly increased availability of adult learning opportunities.

University enrollment has “increased by over 130 percent from 3.04 million to 7.04 million,” largely as a result of government programmes that “provide whole or partial remission of student fees for low-income students. Full costs were paid for students from families whose income was less than 1.5 times the minimum salary, and in the first semester of 2006 there were 800,000 students enrolled under this programme… Expansion of the university sector was accompanied by advice to institutions that they provide a minimum quota for black, the poorest, and American Indian (sic) students.” (Richard Bourne, Lula of Brazil)

An increasing number of Brazilians have access to computers and the internet. In 2013 alone, “the number of households with a personal computer increased by 8.8%, with higher growth in the poor Northeastern region. Today, almost half of Brazilians have a computer at home. Of the 32 million households with computers, 28 million already had access to the internet.”

At all levels of society, the PT is trying to tackle the incredible levels of racial inequality that exist. From the beginning, “Lula signaled that he was serious about social change: Gilberto Gil, the black popular musician who had performed at Lula’s rallies, was made minister of culture; Benedita da Silva, also a black Brazilian, was given a social welfare portfolio… Crístovam Buarque, who had run the University of Brasília and gone on to be governor of Brasília, was put in charge of education; he was a passionate enthusiast for raising the poor standards of state schooling, and an admirer of Paulo Freire” (ibid). A recent innovation is to set aside 50% of places in all federal (ie non-private) universities for students of African or indigenous descent, who have historically been majorly under-represented in higher education.

At all levels of society, the PT is trying to tackle the incredible levels of racial inequality that exist. From the beginning, “Lula signaled that he was serious about social change: Gilberto Gil, the black popular musician who had performed at Lula’s rallies, was made minister of culture; Benedita da Silva, also a black Brazilian, was given a social welfare portfolio… Crístovam Buarque, who had run the University of Brasília and gone on to be governor of Brasília, was put in charge of education; he was a passionate enthusiast for raising the poor standards of state schooling, and an admirer of Paulo Freire” (ibid). A recent innovation is to set aside 50% of places in all federal (ie non-private) universities for students of African or indigenous descent, who have historically been majorly under-represented in higher education.

Lula’s government created a Special Secretariat for Policies for the Promotion of Racial Equality, which has been involved in promoting “the controversial programme to promote racial quotas for university entrance, and support and recognition for two thousand quilombos, the settlements for escaped slaves in the 17th to 19th centuries that were symbols of the survival of African (often Yoruba) culture in Brazil.” (ibid)

Over a million affordable homes have been built, with more on the way. The ‘Luz Para Todos’ (Light For All) programme has brought electricity to 15 million rural Brazilians who didn’t previously have it. It would be difficult to exaggerate the importance of such a measure in terms of social and economic progress – after all, didn’t Lenin famously remark that “Communism is Soviet power plus the electrification of the whole country”?

Crisis management

Much like nearly every other country in the world, Brazil has been negatively affected by the global economic crisis. A large part of its economy is based on the export of primary commodities, for which demand and prices have dropped considerably. As a result, GDP growth over the last three years has been relatively slow.

What’s interesting in the case of Brazil is that, in attempting to tackle its economic problems, it has refused to adopt the austerity policies prescribed by the west. While the working classes of Europe and North America are hit with rising unemployment and the gutting of the welfare state, the Brazilian poor have continued to see increases in jobs, wages and social spending; that is to say, the cost of the recession has been borne largely by the rich rather than the poor. The wealth gap has continued to narrow, just as in the imperialist countries it has continued to widen.

This refusal to adhere to ‘orthodox’ economic policies of ‘fiscal responsibility’ has earned the PT’s economic team the relentless scorn of western neoliberal economists; it is precisely what The Economist and the various other organs of ‘Reaganomic’ policy are complaining about when they accuse Dilma of “mismanaging the economy”. They want to see the economic crisis used as it is being used in Britain (and as it was in Brazil under the dictatorship when crisis hit in the 1970s): as a means to increase inequality; as a means to promote privatisation, deregulation and laissez-faire capitalism; as a means to roll back the gains won by working class and marginalised communities.

Independence from the North and integration with the South

For many centuries Brazil was a Portuguese colony; then for most of the 20th century it was basically a US neocolony, with large parts of its economy controlled by US multinationals, and with its politicians kept in line by the CIA. The period of military dictatorship (1964-85) was characterised by almost total submission to US foreign policy and an enthusiastic acceptance of US leadership in the global crusade against communism. “Never had there been such ideological convergence with the United States.”

Even the post-dictatorship governments of Sarney, Collor and Cardoso kept Brazil largely within the bounds of the Washington Consensus. In the last decade, however, Brazil has been increasingly breaking away from US interference and transforming itself into a genuinely independent state of the Global South. Emir Sader writes that “Brazil was always the privileged ally of the United States, whether it was during the Brazilian military dictatorship (1964–85) or during the government of Cardoso. The Lula government abandoned this inferior position, adopting a clearly multipolar direction in its foreign policy.”

Under successive PT governments, Brazil has become deeply aligned with the progressive wave sweeping Latin America; it plays an enthusiastic role in BRICS and is a strong supporter of multipolarity; it has massively upgraded its relationship with Africa; and it has played a valuable role at the global diplomacy level, for example with its very consistent support for Palestine and its vocal opposition to the Iraq war. The progressive global outlook of the new Brazil is recognised and appreciated across the Global South. For example, during his visit to Brazil in 2010, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad declared that “the world needs Brazil in the UN Security Council because it can help establish a new and more just international order.”

Under successive PT governments, Brazil has become deeply aligned with the progressive wave sweeping Latin America; it plays an enthusiastic role in BRICS and is a strong supporter of multipolarity; it has massively upgraded its relationship with Africa; and it has played a valuable role at the global diplomacy level, for example with its very consistent support for Palestine and its vocal opposition to the Iraq war. The progressive global outlook of the new Brazil is recognised and appreciated across the Global South. For example, during his visit to Brazil in 2010, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad declared that “the world needs Brazil in the UN Security Council because it can help establish a new and more just international order.”

In an excellent article in The Nation, Greg Grandin comments that, “as the region’s economic center of gravity, … Brazil has been absolutely indispensable in countering Washington on trade, war and surveillance… If it were not for Brazil’s often quiet maneuvering over the last thirteen years, Washington would have had the upper hand on any number of issues that would have made the world a nastier, more unstable place — extending its extraordinary rendition and torture program, for instance, isolating Cuba and Venezuela, implementing a hemisphere-wide Patriot Act, or institutionalizing corporate power in [the] ‘Free Trade Area of the Americas’. The diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks a few years ago give a good window onto how Brazilian diplomats gently derailed the United States’ hemispheric agenda; often times, Washington’s envoys were long out of the room before they realized they had been played. Lula recognized Palestine’s claim to a state within its 1967 borders and Dilma spoke out against Israel’s disproportionate use of force in its recent assault on Gaza.”

What a tranformation from the period of the dictatorship, whose generals considered themselves the “great administrators of US interests in the region” and aimed to shape Brazil into “the same sort of boss over the south as the United States is over Brazil itself.” (Open Veins)

Latin America Rising

The project of Latin American regional integration – most strongly associated in our era with the late, great Hugo Chávez – has formed a major part of the agenda of the various progressive Latin American governments over the last 15 years. Chávez’s concept was that, if the closest of economic, political, social and cultural links could be built among the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, these countries would stand a much better chance of successfully standing up to US domination, bribery and destabilisation. This is an idea with deep roots. Nicaraguan analysts Toni Solo and Jorge Capelán state that the pursuit of regional integration is “the legacy of Bolivar, … the legacy of Martí, of Sandino, Mariátegui, Gaitán, Che, Fidel Castro and many other Latin American revolutionaries since Independence. This is so because the colonial and imperial powers needed to split the region up into small countries in order to exploit its resources and labor… In Latin America, it is impossible to engage in the construction of socialist and anti-capitalist alternatives without at the same time struggling to integrate the region politically, economically and even culturally.”

The project of Latin American regional integration – most strongly associated in our era with the late, great Hugo Chávez – has formed a major part of the agenda of the various progressive Latin American governments over the last 15 years. Chávez’s concept was that, if the closest of economic, political, social and cultural links could be built among the countries of Latin America and the Caribbean, these countries would stand a much better chance of successfully standing up to US domination, bribery and destabilisation. This is an idea with deep roots. Nicaraguan analysts Toni Solo and Jorge Capelán state that the pursuit of regional integration is “the legacy of Bolivar, … the legacy of Martí, of Sandino, Mariátegui, Gaitán, Che, Fidel Castro and many other Latin American revolutionaries since Independence. This is so because the colonial and imperial powers needed to split the region up into small countries in order to exploit its resources and labor… In Latin America, it is impossible to engage in the construction of socialist and anti-capitalist alternatives without at the same time struggling to integrate the region politically, economically and even culturally.”

Since the election of Lula in 2002, Brazil has been an active participant in this process. Associated Press journalist Adriana Licon whines that “more than a decade of Workers Party rule has seen Brazil prioritize ties with its leftist regional neighbors, from helping muscle socialist Venezuela into the Mercosur trade bloc to financing a billion-dollar transformation of an industrial port in Cuba.”

The PT government has strongly opposed bilateral deals between individual Latin American countries and the US, and has instead pushed regional blocs. Lula set the tone when, in one of his first major foreign policy decisions, he led the rejection of the US-sponsored Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA). The aim of the FTAA was to cement the unequal trading relationship between North and South America, removing barriers to US investment whilst maintaining the tariffs that protect US markets and producers. At the Summit of the Americas meeting in January 2004 where the FTAA was discussed, Lula correctly noted that the previous decade of free trade policies between North and South America had led to “a decade of desperation” for the people of the South, who live with “the awful reality of widespread and disgracefully increasing poverty.” This historic victory for Latin America was a joint effort of the progressive Latin American governments, including Brazil’s: “[Without the joint leadership] of Hugo Chavez, Evo Morales, Lula da Silva and late Argentinean president Néstor Kirchner, this strategic defeat of imperialism in Latin America would not have been possible.”

The FTAA rejection opened the way for the revival of Mercosur (the Common Market of the South) and other regional bodies that emphasised reciprocity, equality and solidarity. Emir Sader writes that ”the new Brazilian foreign policy allowed and promoted the emergence of new forms of integration and regional cooperation, such as UNASUR, the Bank of the South, the South American Defense Council and the South American Community of Nations. A strong association of diverse countries from across the Global South joined this alliance of Latin American nations, among whom, of course, the BRIC nations — Brazil, Russia, India, and China — are an emblematic example.”

Cuba

Recent developments notwithstanding, maniacal hostility to Cuba has been a central plank of US foreign policy since the first days of the Cuban revolution (in 1959). Since that time, the State Department and the CIA have worked day and night to prevent the emergence of the next Cuba. This strategy has seen direct US interference in Chile, Grenada, Nicaragua, Jamaica, El Salvador, Ecuador and elsewhere (all comprehensively documented in William Blum’s very useful book Killing Hope). As a recent Wall Street Journal article put it, rather mildly: “Cuba remains a lightning rod in US domestic politics and a sticking point for US relations with other Latin nations.”

Recent developments notwithstanding, maniacal hostility to Cuba has been a central plank of US foreign policy since the first days of the Cuban revolution (in 1959). Since that time, the State Department and the CIA have worked day and night to prevent the emergence of the next Cuba. This strategy has seen direct US interference in Chile, Grenada, Nicaragua, Jamaica, El Salvador, Ecuador and elsewhere (all comprehensively documented in William Blum’s very useful book Killing Hope). As a recent Wall Street Journal article put it, rather mildly: “Cuba remains a lightning rod in US domestic politics and a sticking point for US relations with other Latin nations.”

As if to reward the US for its crucial support in the 1964 military coup, the Brazilian dictatorship moved quickly to break diplomatic relations with Cuba. These relations were restored after the fall of the dictatorship (in 1985), but have blossomed under the Lula and Dilma governments. Brazil supports Cuba at the international diplomatic level; it ignores the US economic blockade; and is Cuba’s fourth-largest trading partner (after Venezuela, China and Spain). As Cuba’s then Foreign Minister Felipe Pérez Roque put it in 2008: “Respect, trust, friendship and mutual understanding mark the Cuba-Brazil nexus.” Pushed by the US and the Brazilian right wing to make a critique of Cuba’s human rights record, Dilma Rousseff retorted: “We’re going to begin talking about human rights in the US, in regard to a base called Guantanamo. It’s not possible to use human rights as a political and ideological weapon.”

The most prominent collaboration project to date has been Mais Médicos, as mentioned above. Under this programme, over four thousand Cuban doctors are working “in urban slums and other needy areas such as rural towns, the Amazon River basin and impoverished northeastern states, where medics have long been scarce.” Brazil’s federal government pays for this service with a monthly salary of around $4,000 per doctor, generating desperately-needed foreign currency income for the Cuban state.

The most prominent collaboration project to date has been Mais Médicos, as mentioned above. Under this programme, over four thousand Cuban doctors are working “in urban slums and other needy areas such as rural towns, the Amazon River basin and impoverished northeastern states, where medics have long been scarce.” Brazil’s federal government pays for this service with a monthly salary of around $4,000 per doctor, generating desperately-needed foreign currency income for the Cuban state.

Aside from Mais Médicos, Brazil is also involved in some crucial economic development projects in Cuba, most notably the construction of a port at Mariel. This port – which Brazil’s state development bank is financing to the tune of $680 million – “is located along the route of the main maritime transport flows in the Western hemisphere, and experts say it will be the largest industrial port in the Caribbean in terms of both size and volume of activity.” Unquestionably, this will provide an important boost to Cuba’s economy. Meanwhile, Brazil and Cuba are also planning cooperation in an array of fields. “Brazil has also indicated that it is studying potential investments in generic pharmaceuticals, including anti-cancer drugs, petroleum refining, and the production of lubricants, while Cuban officials have said that Brazil and Cuba are studying projects in the areas of health care, education, computers and agriculture and livestock.”

Brazil has also worked closely with Cuba and Venezuela in the development of a public health system in Haiti. In 2010, Lula’s government set aside $80 billion for this project, with the bulk of the money going to Cuba, which has been using its unparalleled expertise and history of medical solidarity in order to set up a national network of disease control centers and also provide training to Haitian healthcare professionals.

Brazil’s willingness to stand against the US blockade, to cooperate with Cuba and to invest in Cuba is an act of solidarity, and an unambiguous statement of Brazil’s alignment with the socialist and progressive nations.

Venezuela

It’s also significant that Brazil has stood firmly with Venezuela in confronting the ongoing destabilisation campaign it faces. There are more than a few influential journalists who try to drive a wedge between ‘centre-left’ Brazil and ‘ultra-left’ Venezuela (even former poster-boy of the Venezuelan opposition, Henrique Capriles, claimed to be a Lula fan). There are also a few on the left that like to bifurcate ‘revolutionary’ Venezuela and ‘capitulationist’ Brazil: Richard Bourne notes that, while Chávez was greeted as a hero at the January 2005 World Social Forum in Porto Alegre, Lula was jeered. “Some participants accused him of failing to fulfill promises to eradicate Brazil’s mass poverty and of caving in to corporate interests, the IMF, and the United States. Chávez had to defend him. ‘I love Lula!’ he yelled at the stadium. ‘I respect him. Lula is a good guy.’” (Indeed, there is an ultra-left critique of Chávez which is decidedly similar to the ultra-left critique of Lula: “While Chávez talked up twenty-first-century socialism, many economists considered his policies ‘gradualist reform’ that had far more in common with European-style social democracy than Cuban communism. Former Marxist guerrillas such as Douglas Bravo even thought their onetime ally was a sellout. Rather than a revolutionary, Bravo said, Chávez was a neo-liberal.” (Bart Jones – The Hugo Chavez Story from Mud Hut to Perpetual Revolution))

In spite of all this, the two countries under the leadership of Lula, Dilma, Chávez and Maduro have constructed what Raúl Zibechi calls “the most solid strategic alliance in the region.”

In 2003, the trade between the two countries amounted to $800m. By 2011, this figure had gone up to $5bn… In 2005, Lula and Chávez signed the Brazil-Venezuela strategic alliance and in 2007, they started holding quarterly presidential meetings – an unheard-of regularity – to accelerate the integration of infrastructure, which continued until 2010… The friendly relations forged by Chávez and Lula have continued under Rousseff. They present a challenge to those seeking to undermine Venezuela by promoting a so-called “Brazilian” way: in fact the two models are closer than we are led to believe.

As we have seen, Brazil was instrumental in getting Venezuela admitted to Mercosur, the South American trading bloc. “It was the clout of Dilma’s government that persuaded Mercosur to set aside fears about possible violation of its democracy rules and welcome Venezuela into membership.” This bloc, currently comprising Brazil, Venezuela, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay, is increasingly aligned with the general project of regional integration, and provides a counterweight to the Pacific Alliance, whose members – Colombia, Mexico, Peru and Chile – are generally seen as being closer to US-led neoliberal ‘orthodoxy’ (although hopefully this will change with the election of centre-left governments in Chile and Peru).

Lula formed a close friendship with Chávez, and repeatedly threw his weight behind Chávez’ election bids. He underscored his support for the Bolivarian Revolution with a video message in 2012, congratulating Chávez on what would turn out to be his final election:

Under the leadership of Hugo Chávez, the Venezuelan people have made extraordinary conquests. The working classes have never been treated with such respect, care and dignity. Those conquests must be preserved and consolidated. Chávez, count on me, count on us in the PT, count upon the solidarity and support of each militant of the left, of every democrat and every Latin American. Your victory will be our victory. A warm embrace, and thank you comrade for everything that you’ve done for Latin America.

In what turned out to be an important message of support (given Lula’s popularity and the narrowness of the vote), Lula also videoblogged in support of Nicolas Maduro in the presidential election after Chávez’s death: “One phrase sums up what I feel: Maduro for president and a Venezuela that Chávez dreamed of.” President Dilma has also given strong backing to Maduro. “‘We wish you great success with your presidential mandate and your government,’ Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff said after a meeting in which she promised Venezuela food supplies, expanded trade and cooperation in the oil and gas sector… The clear endorsement from the largest and most influential Latin American nation will strengthen Maduro’s grip on power following his contested election in the oil-producing nation last month.”

In what turned out to be an important message of support (given Lula’s popularity and the narrowness of the vote), Lula also videoblogged in support of Nicolas Maduro in the presidential election after Chávez’s death: “One phrase sums up what I feel: Maduro for president and a Venezuela that Chávez dreamed of.” President Dilma has also given strong backing to Maduro. “‘We wish you great success with your presidential mandate and your government,’ Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff said after a meeting in which she promised Venezuela food supplies, expanded trade and cooperation in the oil and gas sector… The clear endorsement from the largest and most influential Latin American nation will strengthen Maduro’s grip on power following his contested election in the oil-producing nation last month.”

Most significantly, the Brazilian leadership gave active solidarity to Venezuela when it was hit by a wave of extended protests and economic sabotage aimed at destabilising the country. Politically, Dilma refused to buckle to pressure to distance herself from Venezuela. Economically, Brazil stepped up to provide the Venezuelan government directly with products being targeted by economic sabotage. Maduro expressed his gratitude:

“We appreciate the spirit of solidarity and support of Brazil and President Dilma Rousseff, who will supply us with all key products that have been hit by this economic war of speculation and hoarding developed by the Venezuelan right. Brazil is our bigger sister, our South American power, we have to thank life, history, God and our commander Chavez that we are placed in this world together as brothers. Our relations are based on respect and solidarity.”

It goes without saying that, under the dictatorship, Brazil would have acted as the US’ regional policeman and done everything within its power to strengthen the Venezuelan opposition – just as they actively supported the forces of the far-right in Chile, Argentina and elsewhere.

Africa

One of Lula’s clearest policies in international relations was to establish close ties with Africa. As he put it, “Brazil – not just me – took a political decision to make a re-encounter with the African continent.” This ambition was not purely borne out of business or geopolitical needs (although these certainly exist), but primarily out a sense of historical obligation – a recognition of the horrors of slavery and its lasting impact on the African continent. (Galeano writes that, “from the conquest of Brazil until abolition, it is estimated that some 10 million blacks were brought from Africa; there are no precise figures for the eighteenth century, but the gold cycle absorbed slave labor in prodigious quantities.”)

Lula, on tour in Cape Verde, stated that “Brazil would not be what it is today without the participation of millions of Africans who helped build our country.” In the course of nine years of his presidency, Lula made a dozen trips to Africa, visiting a total of 25 countries. Visiting the Slave House on Gorée Island, Senegal, in 2005, he apologised for Brazil’s role in the slave trade: “I want to tell you … that I had no responsibility for what happened in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, but I ask your forgiveness for what we did to black people.” If only the governments of certain other countries built on slavery, colonialism and genocide would have so admirable a moral framework!

Brazil retains a strong cultural affinity with Africa – in no small part because it has the largest population of African origin in the world, excluding Africa. “This allowed us to not only begin to repay the historic debt our country has to Africa, but also establish tight connections of economic exchange, supporting large projects in infrastructure and educational and scientific cooperation, from a completely non-paternalistic perspective, and clearly in solidarity and brotherhood.”

Brazil retains a strong cultural affinity with Africa – in no small part because it has the largest population of African origin in the world, excluding Africa. “This allowed us to not only begin to repay the historic debt our country has to Africa, but also establish tight connections of economic exchange, supporting large projects in infrastructure and educational and scientific cooperation, from a completely non-paternalistic perspective, and clearly in solidarity and brotherhood.”

After a period where relations with Africa were almost completely rejected, as the governments of Collor and Cardoso focused instead on cultivating relations with the US, the PT-led Brazil went into a frenzy of activity in relation to Africa diplomacy. Brazil now has a total of 37 embassies in the continent of Africa, up from 17 in 2002. The only countries that have more embassies in Africa are China, the US, Russia and France. “And the love is reciprocated, it seems. Since 2003, 17 African embassies have opened in Brasília, adding to the 16 already there, making the Brazilian capital home to the largest concentration of African embassies in the southern hemisphere.”

The political diplomacy is backed up with aid and trade. “Without attracting much attention, Brazil is fast becoming one of the world’s biggest providers of help to poor countries.” In the last few years, Brazil has been involved in “around 200 cooperation projects with African countries in areas ranging from agricultural research to medicine and technical cooperation, among others.” These cooperation projects include an antiretroviral drug factory in Mozambique; a Human Breast Milk Banks Network in several countries; the training of Angolan military personnel in Brazil; a Mother-Child and Teenage Health Institute in Mozambique; and a $100 million credit facility to help small-scale farmers in Zimbabwe. Announcing the Memorandum of Understanding between Brazil and Zimbabwe, the Brazilian Ambassador in Harare, Marcia Maro da Silva, stated that Brazil would contribute “to the sustainable development of Africa through technical co-operation that comes with no strings attached as it is based on solidarity with no conditionality imposed.”

Brazil is actively involved with the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, through which it works with a number of African countries to strengthen food security, food sovereignty and agricultural research. Its cooperation with Angola and Mozambique (both former Portuguese colonies) is particularly strong. Brazil also aims for maximum knowledge transfer, “strengthening agricultural research capacity in Africa, an area that has for long been neglected by governments and traditional donors.”

Speaking about the recent South-South Cooperation agreement signed between Brazil and Angola, through which Angolan researchers will receive technical assistance and short-term training from the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation, Laurent Thomas, FAO Assistant Director-General for Technical Cooperation, noted that “Brazil has much to offer in terms of proven technical know-how and this agreement is an important milestone in South-South Cooperation between the two countries. We believe it is a model that we hope will be followed by other countries of the Global South.”

Just last year, Dilma announced, on a trip to Addis Ababa to mark the African Union’s 50th anniversary, that Brazil was cancelling nearly a billion dollars’ worth of debt to 12 countries. This debt cancellation would be combined with the setting up of a new development agency.

Meanwhile, in a reflection of ever-deepening Brazil-Africa relations, trade flow between Brazil and Africa grew from $4.3 billion in 2002 to $27.6 billion in 2011. The BNDES, Brazil’s government-owned development bank, has opened its first Africa office, in Johannesburg (its only other international branches are in Montevideo and London).

BRICS – towards a multipolar world

A major developing South American nation such as Brazil has a clear choice in terms of its international outlook: accept the domination (and hope for the protection) of the US, or align closely with the forces of an emerging multipolar world and join the historic struggle to end imperialist hegemony. This multipolar model – “a pattern of multiple centres of power, all with a certain capacity to influence world affairs, shaping a negotiated order“ (Jenny Clegg, China’s Global Strategy) – has been promoted in recent decades by the more advanced political forces of the developing world (in particular the Chinese Communist Party) as the only realistic means of containing imperialism and creating a democratic and stable world order in which formerly oppressed countries can develop in peace.

“It is their common history that brings the BRICS countries together. This is a history that distinguishes the BRICS countries from the traditional powers. It is a history of struggle against colonialism and underdevelopment, including the spirit of Bandung. Circumstances of history have put these countries on the same side.” (Maite Nkoana-Mashabane, South Africa’s Minister of International Relations and Cooperation)

On coming to power in 2003, Lula and the PT made their stance very clear: they would stand with the Global South, with the developing world, with the forces of multipolarity. Visiting China for the first time in 2004, as part of a delegation that included eight cabinet ministers, six state governors and 450 business leaders, Lula pre-empted the emergence of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa):

“He urged China to consider joining the embryonic G3 alliance consisting of Brazil, India and South Africa. ‘We dream that in the near future it will be a G5 with Russia and China,’ Mr Da Silva said. ‘We want to build a political force capable of convincing rich nations … that they can ease their protectionist policies and give access to the so-called developing world.’”

Emphasising the importance of Brazil-China relations, Lula stated: “Many are hoping this alliance is a failure. But there are more people around the world who are on our side than against us.” A huge number of commercial deals and cooperation projects were signed off on this trip, paving the way for a growth in bilateral trade from 6.7 billion dollars in 2003 to more than 80 billion dollars in 2012 (making China Brazil’s number one trading partner since 2009).

As Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi pointed out on a recent visit to Brasilia: “China and Brazil are the largest developing countries in their own hemisphere. Being an important part of the emerging economic entities, our relationship is beyond the traditional scope of bilateral ties, and has strong strategic meanings and extensive significance… China and Brazil should work together to promote the world multipolarisation process, steer the international political and economic order toward a more fair and rational direction, and boost the overall interests of the developing countries.”

Dilma’s government has continued along this path, continuing to cement relations with the BRICS countries and with progressive Latin America (as outlined above). Speaking in late 2012 of Brazil’s growing relationship with Russia, Dilma said: “Our countries champion a multipolar world that reflects the profound transformation humanity is going through.” Brazilian relations with Russia – political and economic – have also blossomed in recent years.

The five BRICS countries constitute around 40 percent of the global population, and are responsible for a fifth of global GDP. Their average econonic growth is 4 percent, compared to 0.7 percent for the G7 countries. As these countries and their allies continue to grow, and as they continue to deepen their unity (developing into what Putin has called “a full-scale strategic cooperation mechanism”), over time they will be able to exercise increasingly meaningful power on the world stage. “The BRICS grouping has shown that the West can no longer co-opt emerging powers into falling into line, even about crucial geopolitical issues,” according Oliver Stuenkel, a professor of international relations at Brazil’s Getulio Vargas Foundation.

Brazil’s enthusiasm for these political projects is a great boon for progressive and anti-imperialist forces worldwide. The day is approaching where the coordinated forces of the developing world can break imperialist hegemony and open the way for the construction of a world that is more just, more peaceful, more prosperous, more equal; a world free from domination, war, hunger and ignorance.

Not creating socialism, but creating the conditions for a transition to socialism

For all the profoundly important and progressive changes that have taken place in Brazil since the PT came to power, capitalism remains firmly in place. Brazil remains a country of vast inequality; there has been no real expropriation of the land owners and big capitalists; land reform has been painfully slow; the political right remains very powerful; the state forces (police, army) have not been overhauled; racist and anti-poor attacks by police are commonplace; the media is still almost exclusively owned by enemy forces; the federal system allows right-wing tyrannies to reign supreme within their own regions; and the basic patterns of ownership have not changed.

For all the profoundly important and progressive changes that have taken place in Brazil since the PT came to power, capitalism remains firmly in place. Brazil remains a country of vast inequality; there has been no real expropriation of the land owners and big capitalists; land reform has been painfully slow; the political right remains very powerful; the state forces (police, army) have not been overhauled; racist and anti-poor attacks by police are commonplace; the media is still almost exclusively owned by enemy forces; the federal system allows right-wing tyrannies to reign supreme within their own regions; and the basic patterns of ownership have not changed.

Brazil remains in many ways a conservative society, where the wealthy exercise far greater influence than they deserve. Meanwhile, it faces some of the same major problems that plague many countries of the Global South in the 21st century: a tension between industrial development and environmental preservation; a tension between tribal, feudal, capitalist and socialist ideologies and ways of life; needing foreign investment but wanting to maintain economic sovereignty; a large population with divisions along several axes – race, religion, ethnicity, region; a highly complex balance of power that involves not just the working class and peasantry but also the old latifundistas, the pro-imperialist elements of the capitalist class, as well as the more nationalistic elements of the capitalist class; a corrupt political system dependent on private campaign financing; and so on.

Frankly, these problems would be a lot easier to deal with if the working class and its allies had a monopoly on political power; that is, if the old elite were expropriated and denied political rights; if the police and army were dismantled and replaced by popular militias that were loyal to the working class and the peasantry; if the deeply flawed system of parliamentary representation were replaced by a genuine popular democracy; that is, if there was a socialist revolution.

The capitalist root of the problem is indeed recognised in the PT programme (approved in 1990 and reaffirmed at the 1999 congress):

“It is capitalist oppression that results in the absolute misery of more than a third of humanity… It is the capitalist system – founded, in the last analysis, on the exploitation of man by man and the brutal commercialisation of human life – that is responsible for frightful crimes against democracy and human rights, from the gas chambers of Hitler to the recent genocides in South Africa, coming to our own sadly celebrated torture chambers. It is Brazilian capitalism, with its predatory dynamic, that is responsible for the hunger of millions, for illiteracy, for social exclusion, and for the violence that is spreading through all parts of national life.” (cited in Bourne)

And yet the tearing down of capitalism and construction of socialism are not simple tasks (what, for example, have you done towards fulfilling them?). It goes without saying that the possibilities for a successful revolutionary process are determined by a number of variables, including: the level of preparedness of the working class; the existence of a tried and tested revolutionary leadership; the building of alliances with other social classes that stand to gain from getting rid of the existing order; a favourable regional context; a favourable global context; a state of crisis in the existing order (breaking the imperialist chain at its weakest link, as Lenin would have it). Global imperialist hegemony – compounded by the fall of the Soviet Union and East European people’s democracies, the rise of global mass media (controlled almost exclusively by the US), US military supremacy, the ever-increasing reach of the CIA and equivalent organisations, the ‘victory’ of neoliberal economics, along with the decline of the left in many parts of the world – serves to make socialist revolution ever more difficult.

Emir Sader explains this phenomenon as follows in his important 2008 article, ‘The Weakest Link’:

”Why has a full-fledged challenge to capitalism not emerged? The answer must be sought in the global balance of forces following the victory of the West in the Cold War. The extensive processes of deregulation and marketization that this unleashed did not produce an era of sustained economic growth; instead, productive investment was in large part transferred to the speculative financial sphere. The social and geographical concentration of wealth has intensified. The limits and contradictions of the capitalist system are revealed on a greater scale than ever before. Yet the subjective factors — forms of collective organization and of consciousness, politics and the state—necessary for the construction of alternatives have been disequipped by these same processes. The state and the public domain have withered under the onslaught of rent-seeking capital, backed by international agencies that relentlessly preach the doctrine of free trade. Ideologically, the triumph of liberalism has imposed its own interpretation of the world as a hegemonic monopoly: democracy could only mean representative parliamentarism; the economy could only mean the capitalist market economy; the client and the consumer occluded the citizen and the worker; competition replaced rights and the market subsumed the public sphere.”

Those Latin American countries in which neoliberalism gained its firmest footing and in which the left was most brutally repressed – Brazil, Chile, Argentina and, to this day, Colombia – clearly have a different balance of class forces to countries such as Venezuela and Bolivia, where the governments have been able to pursue a much more radical and clearly socialist-oriented programme.

The defeat and rebuilding of the Brazilian left

In Brazil, as in most of Latin America, the left was almost completely broken in the 60s, 70s and 80s through brutal repression and the coordinated action of right-wing militarists and the CIA. In the early 1960s, Brazil’s cautiously progressive nationalist government, headed by Joaõ Goulart, “expropriated private oil refineries and decreed that underused landed estates close to roads, railways or federal irrigation projects could be taken over by the state. He said that he was planning to introduce rent controls, to give the vote to illiterates and servicemen, and to change the Constitution” (Bourne). Goulart also demanded independence in foreign policy, for example expanding trade links with (gasp) the Soviet Union and initiating them with the People’s Republic of China. This all proved too much for the far-right and its friends in the US, who put together what the Washington Star at the time described fondly as “a good, effective, old-style coup by conservative military leaders may well serve the best interests of all the Americas” (cited in Open Veins). William Blum gives a flavour of this coup:

“The Brazilian military, with Castelo Branco at its head, overthrew the constitutional government of President Goulart, the culmination of a conspiratorial process in which the American Embassy had been intimately involved. The military then proceeded to install and maintain for two decades one of the most brutal dictatorships in all of South America… In the first few days following the coup, several thousand Brazilians were arrested, ‘communist and suspected communist’ all… political opposition was reduced to virtual extinction, habeas corpus for ‘political crimes’ was suspended, criticism of the president was forbidden by law, labor unions were taken over by government interveners, mounting protests were met by police and military firing into crowds, the use of systematic ‘disappearance’ as a form of repression came upon the stage of Latin America, peasants’ homes were burned down, priests were brutalized… Then there was the torture and the death squads, both largely undertakings of the police and the military, both underwritten by the United States.”

This experience should underscore the need for a highly strategic and nuanced approach to the problem of building and maintaining power for Brazil’s oppressed. Revolutionary strategy must always be rooted in concrete reality, in “seeking truth from facts”, in a thoroughgoing analysis of objective and subjective conditions. The bitter defeat of the Tupamaros in Uruguay, the Fuerzas Armadas Rebeldes and Ejército Guerrillero de los Pobres in Guatemala, and even the constitutional socialism of Unidad Popular in Chile demonstrate all too clearly the strength and responsiveness of US imperialism and its regional allies.

In that context, the rise of the PT has been remarkable, and represents an entirely new era in Brazilian politics. Before the formation of the PT, the Brazilian working class had never had a mass political party to represent it. Although the governments of Goulart and Quadros had been relatively progressive, they represented a forward-looking progressive national bourgeoisie rather than the workers and peasants. The PT, on the other hand, was the product of militant self-organisation of the working class.

In that context, the rise of the PT has been remarkable, and represents an entirely new era in Brazilian politics. Before the formation of the PT, the Brazilian working class had never had a mass political party to represent it. Although the governments of Goulart and Quadros had been relatively progressive, they represented a forward-looking progressive national bourgeoisie rather than the workers and peasants. The PT, on the other hand, was the product of militant self-organisation of the working class.

In the mid-late 1970s, Lula – who had experienced ruthless oppression in both rural and urban form – emerged as Brazil’s preeminent trade unionist and strike leader, standing at the forefront of an industrial working class that had faced decades of intense oppression and repression and which was looking for new forms of political expression. The Workers Party – the Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) – was formed by Lula and his comrades in 1980 as a means of uniting the left forces, providing cohesive leadership to the working class, making a final push to get the military back to barracks, and pursuing political power.

“The PT’s campaign theme was ‘work, land and liberty’. It wanted to end the dictatorship, to end hunger, to provide land and better wages for rural workers, to promote better health and less profit from illness, to define access to education and culture as a right, not a class privilege, to promote equality and an end to discrimination, to prevent the stealing of public money, to end the exploitation of public contracts by private companies, and, in a rhetorical flourish, to claim ‘power to the workers and the people – the workers’ struggle is the same all over the world – only socialism will solve our problems once and for all.’” (Bourne)

Lula and the PT found a way to mobilise, energise and organise the working class, whilst pursuing a political programme that was broad enough to ally wider sections of society behind it. Where they were able to win power at a regional level, they focused on promoting a much richer vision of democracy than that represented by the weak parliamentarism of the post-dictatorship governments. Bourne notes: “Capturing power in Porto Alegre in the mid-1980s, the PT resolved to share it with local communities, especially the poor, by means of a series of public meetings to set the budget. The process was inspired … partly by the ideas of the educationist Paulo Freire, who linked learning by doing to a deeper public ownership of democracy… The process had measurable social benefits, especially in poorer neighbourhoods, with the building of fifty schools, improvements to the housing stock, and a rise in coverage of the sewer system from 46 percent to 86 percent of the city in just over a decade… There was even a significant drop in school truancy.”

Marx and Engels wrote in the Communist Manifesto that “the proletariat must first of all acquire political supremacy, must rise to be the leading class of the nation, must constitute itself the nation.” In a sense, this is precisely the process represented by the rise of the PT, which has always focused not just on improving the standard of living of the oppressed but on engaging the oppressed in the task of running society in their own interests, thereby deepening the democratisation process and creating a mobilised, educated working class and peasantry. As Richard Bourne points out, as a result of the PT’s strategy, “for the first time ever, the working class would occupy centre stage of the country’s political scene.” It shouldn’t be difficult to understand how this helps to create the conditions necessary for building socialism. Tereza Campello, the current Minister for Social Development and the Fight against Hunger (quite a portfolio!), makes clear the link between poverty alleviation and empowerment: “Critics quote Confucius and say it is better to teach people how to fish than to give them fish, but bolsa familia recipients aren’t poor because they are lazy or don’t know how to work, they are poor because they have no opportunities, no education and poor health. How can they compete with those disadvantages? By giving people the money to survive, we are empowering them, including them and giving them the rights of a citizen in a consumer society.”

The PT’s rise in the 1980s marks the beginning of the recovery of the Latin American left, which, a quarter of a century later, holds power across the greater part of the continent and can truly claim to have recovered from the darkest days of dictatorship. As Lula himself says:

“In 1990, when we created the Sao Paulo Forum, we never imagined that two decades later we would get to where we are now. In that era, the left was only in power in Cuba. Today, we govern a great number of countries, and even where we are in the opposition, the parties of the Forum have a growing influence in political and social life. The progressive governments are changing the face of Latin America. Thanks to them, our continent is developing itself at an ever-accelerating pace, with economic growth, job creation, distribution of wealth and social inclusion. Today we are the international reference of a victorious alternative to neoliberalism.

This continental recovery would have been impossible but for the creative strategic thinking of people like Lula, Hugo Chávez, Daniel Ortega, the Kirchners in Argentina, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, and others. Across the continent, progressive movements have found ways to start to capture power in order to empower the masses and move in the direction of socialism. The progress made has required a great deal of tactical flexibility and a willingness to make a deep study of existing conditions rather than rely on dogma. All sorts of compromises and shaky class alliances have been, and continue to be, required. As Joe Slovo wrote in relation to South Africa: “By rejecting class alliances and going it alone, the working class would in fact be surrendering the leadership of the national struggle to the upper and middle strata… Along this path, ‘class purity’ will surely lead to class suicide and ‘socialist’- sounding slogans will actually hold back the achievement of socialism.” The question is one of whether to play the game, to whatever extent it is possible, in the interests of the workers and oppressed; or whether it is better simply to leave politics to the old rich-and-white elite with their mansions, their helicopters and their Washington connections.

This continental recovery would have been impossible but for the creative strategic thinking of people like Lula, Hugo Chávez, Daniel Ortega, the Kirchners in Argentina, Rafael Correa in Ecuador, and others. Across the continent, progressive movements have found ways to start to capture power in order to empower the masses and move in the direction of socialism. The progress made has required a great deal of tactical flexibility and a willingness to make a deep study of existing conditions rather than rely on dogma. All sorts of compromises and shaky class alliances have been, and continue to be, required. As Joe Slovo wrote in relation to South Africa: “By rejecting class alliances and going it alone, the working class would in fact be surrendering the leadership of the national struggle to the upper and middle strata… Along this path, ‘class purity’ will surely lead to class suicide and ‘socialist’- sounding slogans will actually hold back the achievement of socialism.” The question is one of whether to play the game, to whatever extent it is possible, in the interests of the workers and oppressed; or whether it is better simply to leave politics to the old rich-and-white elite with their mansions, their helicopters and their Washington connections.

One undeniable virtue of the progressive governments of Latin America is that they continue to exist, and continue to exercise political power in the interests of the masses. They make all sorts of compromises with local and international capital, but such is the nature of reality. Better to pursue a relatively cautious, socialist-oriented programme than to be overthrown by a CIA-backed junta. What the PT government is doing is objectively – in the long-term and on a global scale – revolutionary, because they are creating favourable conditions for breaking imperialist domination and constructing socialism in the future. The PT and its allies have been able to:

- Rebuild a vibrant, powerful, vocal left

- Establish a stable democracy with vastly expanded participation

- Establish a government that incorporates some of the most revolutionary voices in the country (including Communist Party of Brazil (PCdoB) members in the cabinet)

- Establish some level of economic and political independence from the US

- Make impressive progress in reducing poverty, inequality and prejudice

- Align Brazil with the increasingly-dominant progressive trend in Latin America

- Align Brazil with an emerging multipolar world that has the potential to break imperialist domination for once and for all.

Taken together, these elements constitute historic progress. In the words of Francisco Dominguez (Secretary of the Venezuela Solidarity Campaign, speaking at the recent Latin America Conference in London), the PT government is the most important gain made by the Brazilian people in their history.

Support the PT

It should be clear that socialists, communists, anti-imperialists and progressive people worldwide have a duty to support the PT, along with the rest of rising Latin America.

Dilma’s recent victory in the presidential election creates 16 years of uninterrupted PT-led rule. The coming period will throw up all manner of problems and difficulties, in terms of expanding the united front, returning to economic growth, continuing to deliver to the poor (and improving still further on this) and reducing the scope of the conservative elite to disrupt and destabilise – the remarkable unity of international capital and its local representatives around the election campaign of Aécio Neves demonstrates that the Brazilian right is very much still a force to be reckoned with.

If possible, steps should be initiated to move beyond simple parliamentary democracy – to start to institutionalise the rule of working people and their allies; to create an anti-imperialist, national democratic state, as is being done, to varying degrees and in different ways, in Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador and Nicaragua. Easier said than done, of course, especially whilst broadening rather than narrowing the united front. But Dilma’s talk of a constitutional convention could conceivably provide an opening to initiate this process.

Brazil’s continuation down the progressive, democratic, anti-imperialist path forged by the PT is crucial to Latin America, to BRICS, to the entire developing world, and to working people everywhere. May it enjoy continued success.