On 5 December 2013, the progressive forces of the world lost one of their greatest strategists and toughest fighters, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela. Mandela was, in the words of South African Communist Party General Secretary Blade Nzimande, “a brave and courageous soldier, patriot and internationalist who, to borrow from Che Guevara, was a true revolutionary guided by great feelings of love for his people, an outstanding feature of all genuine people’s revolutionaries.”

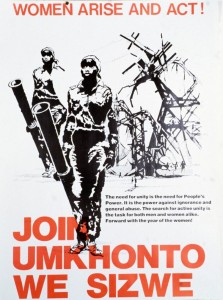

The legacy of Nelson Mandela and of the organisations that he did so much to shape – the African National Congress, the South African Communist Party, and Umkhonto weSizwe (Spear of the Nation) – deserves to be celebrated, studied and emulated. And yet, this legacy is under attack from both left and right.

On the one hand, we have those late-to-the-party self-proclaimed lovers of freedom and democracy: the representatives of western imperialism who want us to forget that they supported apartheid to the hilt. Such people want to claim Mandela’s legacy for themselves; they want to bask in the reflected glory of his message of reconciliation and unity, believing that it serves to sweep their criminal past under the carpet.

On the other hand, we have 57 varieties of ultra-left windbag who think that Madiba and the ANC sold out the struggle – that Mandela capitulated to imperialism and that the South African masses’ walk to freedom was aborted by the ANC’s compromises. They feel that Mandela’s “elevation into a universal hero was the mask of a bitter defeat”; that the ANC leadership was bamboozled into a neoliberal economic model that “enriched the few and dumped the poor”; that any useful change that might have occurred in post-apartheid South Africa has been “undercut by the extremes and corruption of a ‘neoliberalism’ to which the ANC devoted itself.”

In the following article, I will attempt to show that Nelson Mandela – as part of the wider leadership of the liberation struggle – acted with exceptional creativity, bravery and strategic brilliance in pursuit of meaningful and lasting change in South Africa.

Further, I will attempt to demonstrate that, in spite of exceptionally difficult domestic and international circumstances, the liberation movement has managed to make impressive progress towards the fulfilment of its historic aims of equality, justice, solidarity, freedom, democracy and shared prosperity, as laid out in the Freedom Charter.

I hope also to demonstrate that Nelson Mandela, far from being a fluffy liberal whose actions were perfectly acceptable to the prevailing imperialist order, was by any reasonable measure one of the great revolutionaries of the twentieth century; a man who fought ceaselessly against racism, imperialism and colonialism, by any means necessary.

Lastly, I will argue that the current fashion (seemingly all-pervasive in the western left) of heaping abuse on the ANC – exaggerating its perceived failures and ignoring its successes – is not in the slightest bit consistent with the principles and political practice of Nelson Mandela, and that disunity in the ranks of the liberation movement serves nobody but the right wing and their allies in international capital.

The break with passive resistance

Mandela’s first major contribution to revolutionary strategy in South Africa was to push the ANC to end its half-century-old policy of strictly passive resistance and towards a strategy of armed struggle.

The African National Congress had been heavily influenced by the nonviolent philosophy of Mohandas Gandhi, who lived in South Africa from 1893 to 1914 and who was among the founders of the Natal Indian Congress, an organisation set up to fight discrimination directed at the Indian population in South Africa. The ahimsa concept of nonviolence, which became a major cornerstone of the Indian independence movement, continued to inspire the ANC and its allies well into the 1940s.

As a founder member of the ANC Youth League in 1944 (along with Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu and others), Mandela quickly rose to prominence as a capable and courageous young leader. Along with others in the Youth League, he successfully advocated a move away from purely passive resistance and towards nonviolent direct action. This led in 1952 to the adoption of the Defiance Campaign – a wide-ranging campaign for mass defiance of racist laws. In the short course of the campaign, over eight thousand volunteers accepted imprisonment as part of a disciplined mass protest in which they defied banning orders, gagging orders and segregation laws. The effect on the ANC and the country was electric:

There was a wave of national consciousness and national unity of all the oppressed, unprecedented in the history of the country … For the first time in its history the country witnessed a united and determined campaign embracing all the oppressed peoples under a single leadership, thus marking a turning point in the forms and methods of struggle hitherto conducted. In a relatively short period of time, the Congresses had organised a force of 8,557 highly disciplined volunteers who courted imprisonment. In the less than nine months that the campaign lasted, the membership of the African National Congress shot up from a mere 7,000 to over 100,000, and the ANC established itself as the undoubted leader of the struggle for democracy, freedom and national liberation in South Africa. The campaign transformed the ANC from a loose-knit body into an effective mass movement, with branches in almost every single area in the country and with offices manned by full-time personnel in all the major centres.

Although the campaign was wildly successful in terms of raising popular consciousness and moving the liberation struggle forward, it soon became clear that it wasn’t going to be sustainable. The selflessness and courage of the protestors did not have the effect of drawing out some latent humanitarian morality in the apartheid government; on the contrary, the state responded with heavy repression: killings, harsh prison sentences, more bannings, and a concerted effort to cut the campaign’s leadership off from the masses. In this context, the strategy of the ANC and its allies had to evolve once again.

In his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela writes:

Non-violent passive resistance is effective as long as your opposition adheres to the same rules as you do. But if peaceful protest is met with violence, its efficacy is at an end. For me, non-violence was not a moral principle but a strategy; there is no moral goodness in using an ineffective weapon. Over and over again, we had used all the non-violent weapons in our arsenal – speeches, deputations, threats, marches, strikes, stay-aways, voluntary imprisonment – all to no avail, for whatever we did was met by an iron hand. A freedom fighter learns the hard way that it is the oppressor who defines the nature of the struggle, and the oppressed is often left no recourse but to use methods that mirror those of the oppressor. At a certain point, one can only fight fire with fire.

For an organisation that had always operated above ground, the idea of armed struggle was by no means welcomed by everyone. Mandela, who had made a detailed study of the world’s socialist and liberation movements, led the argument:

I was candid and explained why I believed we had no choice but to turn to violence. I used an old African expression: ‛Sebatana ha se bokwe ka diatla’ (‛The attacks of the wild beast cannot be averted with only bare hands’). Moses [Mabhida] was a long-time communist, and I told him that his opposition was like the Communist Party in Cuba under Batista. The party had insisted that the appropriate conditions had not yet arrived, and waited because they were simply following the textbook definitions of Lenin and Stalin. Castro did not wait, he acted – and he triumphed. If you wait for textbook conditions, they will never occur. I told Moses point blank that his mind was stuck in the old mould of the ANC’s being a legal organisation. People were already forming military units on their own, and the only organisation that had the muscle to lead them was the ANC. We had always maintained that the people were ahead of us, and now they were.

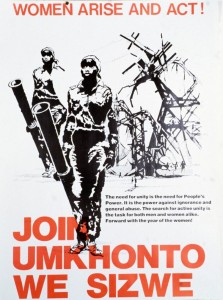

Spear of the Nation

The stepped-up repression in the light of the Defiance Campaign, and most importantly the notorious Sharpeville Massacre of 21 March 1961, led inexorably to the commencement of armed resistance.

The stepped-up repression in the light of the Defiance Campaign, and most importantly the notorious Sharpeville Massacre of 21 March 1961, led inexorably to the commencement of armed resistance.

In a series of high-level meetings in mid-1961, Mandela argued that the ANC must take the lead in setting up an organisation of armed resistance to apartheid. After many long nights of arguing, it was accepted that armed struggle was necessary, and Nelson Mandela and Joe Slovo were tasked with setting up the military organisation. Umkhonto we Sizwe (meaning Spear of the Nation), better known by the acronym ‘MK’, was launched on 16 December 1961 with a series of bomb attacks against government structures in Johannesburg, Port Elizabeth and Durban.

Mandela wrote of the early discussions defining the MK’s strategy and tactics:

In planning the direction and form that MK would take, we considered four types of violent activities: sabotage, guerrilla warfare, terrorism and open revolution. For a small and fledgling army, open revolution was inconceivable. Terrorism inevitably reflected poorly on those who used it, undermining any public support it might otherwise garner. Guerrilla warfare was a possibility, but since the ANC had been reluctant to embrace violence at all, it made sense to start with the form of violence that inflicted the least harm against individuals: sabotage. Because it did not involve loss of life, it offered the best hope for reconciliation among the races afterwards. We did not want to start a blood-feud between white and black. Animosity between Afrikaner and Englishman was still sharp fifty years after the Anglo-Boer war; what would race relations be like between white and black if we provoked a civil war? Sabotage had the added virtue of requiring the least manpower. Our strategy was to make selective forays against military installations, power plants, telephone lines and transportation links; targets that would not only hamper the military effectiveness of the state, but frighten National Party supporters, scare away foreign capital, and weaken the economy. This we hoped would bring the government to the bargaining table. Strict instructions were given to members of MK that we would countenance no loss of life. But if sabotage did not produce the results we wanted, we were prepared to move on to the next stage: guerrilla warfare and terrorism.

The work of the MK went through several phases: the sabotage operations of the early 60s; a period of relative inactivity resulting from the capture and imprisonment of most of its leadership (including Mandela); the establishment of military camps in Tanzania, Zambia, Angola and Mozambique; the training of thousands of South African cadres in the Soviet Union and the German Democratic Republic; the vastly-expanded sabotage campaign of the 1980s; and the mission to infiltrate dozens of senior ANC and MK leaders back into South Africa to help lead the underground struggle against apartheid.

From the beginning, the aim of Umkhonto was not to win a military victory against apartheid – there were too many factors militating against that. As Joe Slovo noted, with his characteristic irony: “Reality shows that, contrary to other countries in southern Africa, we have no basis for a classical guerrilla struggle. We have never had a hinterland, and we do not expect to.”

Furthermore, the movement had to take into account the efficiency, size, experience, resources and sheer brutality of apartheid South Africa’s security services. “The enemy has at his disposal a mighty military machine and an enormous apparatus for reprisal. This combination of factors continues to make us place our main emphasis on the political struggle. (ibid).

Ultimately, the MK’s activities served as “armed propaganda“: shattering the illusions of apartheid invincibility; inspiring activists on the ground in the townships and trade unions; disrupting what martyred Umkhonto chief of staff Chris Hani called the “sweet life” enjoyed by the white South African population; and, crucially, breaking “the paralysing impotence that inevitably prevailed as a result of the centuries of the white minority’s predominance”.

The combination of revolutionary violence with mass civil resistance was designed to provoke a crisis in the enemy’s camp that would at least force them to the negotiating table. In this, it was largely successful.

At all times, the MK’s work was linked up with the broader global struggle against imperialism, and especially the Africa-wide struggle against European colonialism. Mandela spent the first few months of 1962 in Africa, his first port of call being Ethiopia, where he was a delegate to a meeting of the punchily-named Pan-African Freedom Movement for East, Central and Southern Africa (PAFMECSA). At this event, he called for the unity of Africa’s anti-colonial and anti-racist forces, and emphasised the role of revolutionary violence: “Force is the only language the imperialists can hear, and no country became free without some sort of violence”.

Mandela’s autobiography Long Walk to Freedom contains the following fascinating passage about the study he did when preparing the start of the armed struggle:

“Any and every source was of interest to me. I read the report of Blas Roca, the general secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba, about their years as an illegal organisation during the Batista regime. In Commando by Deneys Reitz, I read of the unconventional guerrilla tactics of the Boer generals during the Anglo-Boer War. I read works by and about Che Guevara, Mao Zedong, Fidel Castro. In Edgar Snow’s brilliant Red Star Over China I saw that it was Mao’s determination and non-traditional thinking that had led him to victory.”

This quote is remarkable for the insight it gives into Mandela’s creative thought as well as his political leanings. For one thing, it’s interesting for a black South African liberation fighter to look to his oppressor for lessons in revolutionary warfare, and it took a brilliant mind like Mandela’s to see the parallels between the African struggle against apartheid and the Afrikaner struggle against British imperialism. He saw that there was an anti-colonial kernel lying somewhere beneath the despicable and inhumane exterior of Boer rule, and he identified a self-image of rebelliousness that he was able to play to decades later in order to win sections of the Afrikaner people over to the project of reconciliation and nation-building.

Another interesting aspect of the quote above is that the MK – whose leadership was shared between the ANC and the South African Communist Party (SACP) – was obviously looking to the socialist world for inspiration. The Soviet Union became the major supplier of training, weapons, finance and diplomatic support for the ANC (as detailed in Vladimir Shubin’s very useful book ANC: A View From Moscow), but it was to China and Cuba – the countries that had combined the fight for national sovereignty with the struggle for socialism – that the fledgling South African armed liberation movement looked for strategic inspiration.

As for Mao’s “determination and non-traditional thinking”, it’s clear that Nelson Mandela shared these strengths which – along with his legendary compassion and belief in the human spirit – constituted essential weapons in the struggle for freedom. There was never any guarantee that apartheid would fall. If it weren’t for the heroic resistance and strategic brilliance of the liberation movement, apartheid would likely still be in place. Political struggle requires not just determination (the sort of determination that allows you to remain a revolutionary through 27 years of prison), but also a deep understanding of your own forces and those of your enemy; flexibility; creativity; the will to fight and the will to negotiate. All of these, Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela had in abundance.

Communism, non-racialism and the SACP

One somewhat unfashionable fact about Nelson Mandela is that he was – at least at the time of his arrest in August 1962 – a communist. The ANC and SACP had always denied Mandela’s party membership, so as not to add grist to the mill of the apartheid state’s complaint that the anti-apartheid struggle was an extension of the ‘global communist threat’, directed from Moscow; however, in the SACP’s obituary of Mandela it was acknowledged – without doubt by prior arrangement with Mandela himself – that he had been a central committee member of the South African Communist Party.

Mandela’s party membership serves to emphasise the longstanding alliance between the ANC and the SACP – a relationship which has been decisive in shaping the liberation movement. The fruits of this alliance can be summarised as follows:

- A non-racialist approach to participation in the freedom struggle. The ANC/SACP policy was that the struggle against apartheid, whilst primarily fought in the interests of the most oppressed group (black Africans), was also a struggle to transcend the division of society along racial lines, and that therefore the struggle should embrace people of all races, so long as they were genuinely committed to a non-racial democracy.

As explained in the ANC’s classic Strategy and Tactics document: “Our policy must continually stress in the future (as it has in the past) that there is room in South Africa for all who live in it but only on the basis of absolute democracy … Committed revolutionaries are our brothers, regardless of the group to which they belong. There can be no second class participants in our Movement. It is for the enemy we reserve our assertiveness and our justified sense of grievance”. This policy proved very effective, as it frustrated the apartheid state’s never-ending attempts to cause tensions between blacks and Indians, between Xhosa and Zulu, between white progressives and African nationalists, and so on. Furthermore, it created a precedent of unity and respect that constitutes the basis for a new, post-apartheid national identity.

- Alignment of the South African national struggle with the global socialist forces. This led to the ANC receiving abundant practical support from the socialist countries, in particular the USSR and the German Democratic Republic. In addition to the provision of funds and diplomatic solidarity at all levels, military and political training was given to literally thousands of MK fighters.

- The working class and oppressed masses were seen as the major support base of the liberation struggle, and progress continues to be measured primarily in terms of how much it benefits those that suffered most under apartheid.

Mandela’s life story has been so thoroughly white-washed that his relationship with the SACP is rarely talked about. But Mandela himself never tried to play down the role of the SACP, nor would he succumb to the demands of the western powers and the apartheid state that the SACP be pushed out of the alliance tent.

The ANC made numerous necessary – if painful – compromises in order to attain the release of Mandela and his comrades; in order to begin meaningful negotiations towards the end of apartheid; in order to achieve the unbanning of the ANC and other banned organisations; in order to gain support at UN level for the ending of apartheid; in order to avoid civil war and anarchy; in order to avoid capital flight and economic collapse. And yet it has never submitted to intense pressure to break its alliance with the SACP. Responding to the apartheid government’s statement that it would not negotiate with the ANC while it was so closely associated with communists, Mandela wrote to then Prime Minister PW Botha in 1989:

“No dedicated ANC member will ever heed a call to break with the SACP. We regard such a demand as a purely divisive government strategy. It is in fact a call on us to commit suicide. Which man of honour will ever desert a lifelong friend at the instance of a common opponent and still retain a measure of credibility among his people? Which opponent will ever trust such a treacherous freedom fighter? Yet this is what the government is, in effect, asking us to do – to desert our faithful allies. We will not fall into that trap.”

Mandela continued to defend and promote the role of the SACP during his tenure as President (1994-99). In his report to the 50th National Conference of the ANC in December 1997, he remarked:

Over the decades, including the last three years, the SACP has proved itself to be our steadfast ally in the struggle to end white minority domination and its legacy, and to create a genuinely non-racial society. It is on the basis of this common commitment that we, the ANC, look forward to the further strengthening of our relations with the SACP to promote this common objective of the national democratic movement.

The ANC-SACP alliance remains strong up to the present day. There are four SACP members in the Cabinet, and many senior figures in the ANC are also SACP members (including Gwede Mantashe, the ANC’s secretary general). The SACP continues to be the largest and most influential communist party in the continent of Africa.

Nelson Mandela’s philosophy may have been reduced by certain of his latter-day admirers to a sort of harmless-old-man liberalism, but his actual words and deeds provide clear evidence of his militant commitment to the cause of the most oppressed. He identified with any ideology that promoted the interests of the ‘wretched of the earth’, no matter if that ideology was (and is) considered in the west as the epitome of evil. In his famous speech at the Rivonia Trial, he commented:

It is perhaps difficult for white South Africans, with an ingrained prejudice against communism, to understand why experienced African politicians so readily accept communists as their friends. But to us the reason is obvious… For many decades communists were the only political group in South Africa who were prepared to treat Africans as human beings and their equals; who were prepared to eat with us; talk with us, live with us, and work with us. They were the only political group which was prepared to work with the Africans for the attainment of political rights and a stake in society. Because of this, there are many Africans who, today, tend to equate freedom with communism.

The extended reflections in his autobiography on how he overcame his own prejudice against communism and how he came to value Marxist thought are so fascinating as to be worth quoting at length:

I had little knowledge of Marxism, and in political discussions with my communist friends I found myself handicapped by my ignorance of their philosophy. I decided to remedy this. I acquired the complete works of Marx and Engels, Lenin, Stalin, Mao Zedong and others, and probed the philosophy of dialectical and historical materialism. I had little time to study these works properly. While I was stimulated by the Communist Manifesto, I was exhausted by Das Kapital. But I found myself strongly drawn to the idea of a classless society which, to my mind, was similar to traditional African culture where life was shared and communal. I subscribed to Marx’s basic dictum, which has the simplicity and generosity of the Golden Rule: ‛From each according to his ability; to each according to his needs.’

Dialectical materialism seemed to offer both a searchlight illuminating the dark night of racial oppression and a tool that could be used to end it. It helped me to see the situation other than through the prism of black and white relations, for if our struggle was to succeed, we had to transcend black and white. I was attracted to the scientific underpinnings of dialectical materialism, for I am always inclined to trust what I can verify. Its materialistic analysis of economics rang true to me. The idea that the value of goods was based on the amount of labour that went into them seemed particularly appropriate for South Africa. The ruling class paid African labour a subsistence wage and then added value to the cost of the goods, which they retained for themselves.

Marxism’s call to revolutionary action was music to the ears of a freedom fighter. The idea that history progresses through struggle and that change occurs in revolutionary jumps was similarly appealing. In my reading of Marxist works, I found a great deal of information that bore on the types of problems that face a practical politician. Marxists gave serious attention to national liberation movements, and the Soviet Union in particular supported the national struggles of many colonial peoples. This was another reason why I amended my view of communists and accepted the ANC position of welcoming Marxists into its ranks.

A friend once asked me how I could reconcile my creed of African nationalism with a belief in dialectical materialism. For me, there was no contradiction. I was first and foremost an African nationalist fighting for our emancipation from minority rule and the right to control our own destiny. But, at the same time, South Africa and the African continent were part of the larger world. Our problems, while distinctive and special, were not unique, and a philosophy that placed those problems in an international and historical context of the greater world and the course of history was valuable. I was prepared to use whatever means necessary to speed up the erasure of human prejudice and the end of chauvinistic and violent nationalism… I found that African nationalists and African communists generally had far more to unite them than to divide them.

This is a profound statement of the case for an alliance of communist and national liberation forces, and has application well beyond the boundaries of South Africa.

From armed struggle to negotiations

Having been so closely associated with the transition from nonviolence to armed struggle, there is poetry in the fact that Mandela is also closely associated with the suspension of the armed struggle in 1990 and the move towards a negotiated end to apartheid.

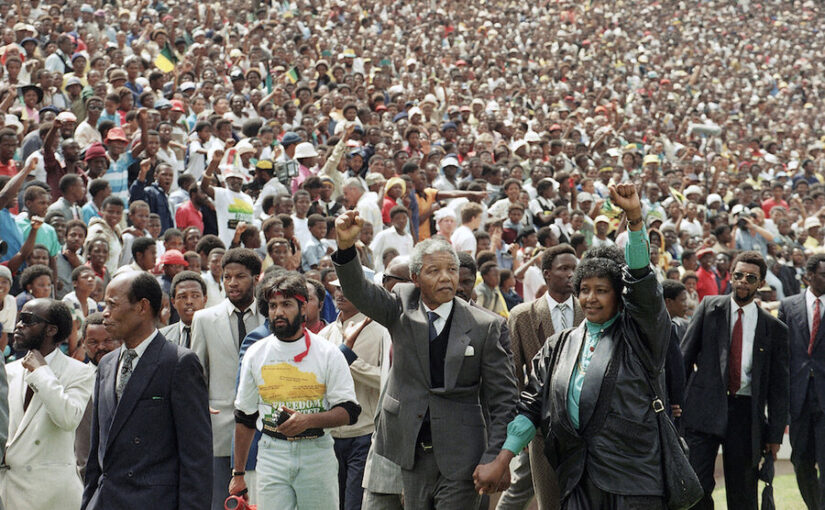

The National Party government had long insisted that the suspension of the armed struggle by the ANC/MK was a precondition for negotiations, and the ANC in turn had long insisted that there was no question of ending armed struggle whilst the government refused to negotiate and whilst its police and army were waging war against the black population. It is well known that Mandela could have won his release from prison many years earlier had he been willing to renounce the armed struggle. His principled and powerful response to these offers – read by his daughter Zindzi to a mass rally in Soweto in February 1985 – is now a classic document of the struggle:

I am not a violent man… It was only when all other forms of resistance were no longer open to us that we turned to armed struggle. Let Botha renounce violence. Let him say that he will dismantle apartheid. Let him unban the people’s organisation, the African National Congress. Let him free all who have been imprisoned, banished or exiled for their opposition to apartheid. Let him guarantee free political activity so that people may decide who will govern them.

I cherish my own freedom dearly, but I care even more for your freedom. Too many have died since I went to prison. Too many have suffered for the love of freedom. I owe it to their widows, to their orphans, to their mothers and to their fathers who have grieved and wept for them. Not only I have suffered during these long, lonely, wasted years. I am not less life-loving than you are. But I cannot sell my birthright, nor am I prepared to sell the birthright of the people to be free. I am in prison as the representative of the people and of your organisation, the African National Congress, which was banned.

Only free men can negotiate. Prisoners cannot enter into contracts… I cannot and will not give any undertaking at a time when I and you, the people, are not free. Your freedom and mine cannot be separated. I will return.

Given that the ANC leadership had stuck to its principled position on armed struggle for nearly three decades, many in the movement were surprised and dismayed when, in August 1990, the Pretoria Minute was signed, announcing that, “in the interest of moving as speedily as possible towards a negotiated peaceful political settlement … no further armed actions and related activities by the ANC and its military wing Umkhonto we Sizwe will take place.”

To some, this was betrayal. Indeed, there remain elements within the South African left (along with those comfortable middle-class radical intellectuals in the west who absolutely insist on third world liberation movements pursuing the most militant possible strategy) who still feel that the armed struggle should have continued to the bitter end.

However, this misses the point that circumstances had changed in several significant ways. Firstly, the ANC and other liberation organisations had been unbanned, political prisoners freed, political exiles returned, and serious negotiations towards democratic elections begun. With these victories – won through armed struggle, mass defiance, strikes, international pressure, and the changing military-political situation in southern Africa as a whole (thanks in no small part to the heroic intervention by Cuba at Cuito Cuanavale) – there was little justification or mandate for the continuation of the armed struggle. “While it had always accepted the human and material cost of protracted struggle, the ANC had, as a matter of abiding principle, sought a more humane resolution of the conflict without compromising the basic objectives of struggle” (source). Another decisive factor is that the USSR – by far the biggest backer of the MK – was by this time in a state of turmoil (it ceased to exist little over a year later), and its willingness and ability to support a guerrilla army were much reduced (the decline and fall of the USSR was deeply felt by socialist and national liberation movements across the world, from Ireland to Latin America to Southern Africa).

The suspension of the armed struggle removed a major roadblock to progress in the negotiations, and also served to focus attention on the most lunatic sections of the Afrikaner right-wing, who were armed to the teeth and perfectly willing to wage a war rather than accept transition to a non-racial democracy. That no such war took place is testament to the correctness – brilliance, even – of the ANC’s tactics at this point.

Although Chris Hani is sometimes put forward as a more courageous and militant politician who would have saved South Africa from the endlessly compromising Mandela, it is a matter of recorded fact that Hani unambiguously supported the ceasefire, for example writing in 1991: *”In the current political situation, the decision by our organisation to suspend armed action is correct and is an important contribution in maintaining the momentum of negotiations.”

Building a new South Africa

The first democratic elections of 1994, won by the ANC with a clear majority (63% to the National Party’s 20%), did not establish a socialist utopia. The vast inequality, the desperate poverty, the white privilege, the male domination, the corporate power, the white-owned press, the intense violence: the accumulated injustice of three and a half centuries of colonial white supremacy didn’t go away overnight. The aims set out in the Freedom Charter were not instantly achieved, and indeed some of them still seem far off, two decades later.

The first democratic elections of 1994, won by the ANC with a clear majority (63% to the National Party’s 20%), did not establish a socialist utopia. The vast inequality, the desperate poverty, the white privilege, the male domination, the corporate power, the white-owned press, the intense violence: the accumulated injustice of three and a half centuries of colonial white supremacy didn’t go away overnight. The aims set out in the Freedom Charter were not instantly achieved, and indeed some of them still seem far off, two decades later.

To some, this apparent failure is an indication of Mandela having “sold out”: the whites offered him ‘apartheid lite’ – a continuation of the semi-colonial status quo but with the addition of a few smiling black faces in the government – and he went for it. To others, any failings of post-apartheid South Africa can be traced to Mandela and his comrades being dazzled by neoliberal economics and therefore turning their back on the socialist-oriented economic path laid out in the Freedom Charter.

Both of these narratives tend to ignore the very important progress that the South African government has made over the last two decades. Both narratives also tend to downplay the fact that the ANC, in negotiating an end to apartheid and leading the first democratic government, faced economic, political and social problems of almost unimaginable dimensions. It inherited a society that was bitterly divided, characterised by fear, distrust, hatred and violence. Apart from the obvious threat from the Afrikaner far-right, there were also deep divisions within the black community (carefully nurtured by the apartheid state over the course of many decades). The threat of civil war – from a combination of white fascists, Inkatha Freedom Party tribalists and bantustan leaders – was all too real, and a serious structural collapse or civil war could easily have led to foreign intervention and the type of hell that Mozambique and Angola endured for nearly two decades after liberation.

On the economic front, there was a clear possibility of total collapse if the corporations decided to sabotage the economy. There was also a threat of a major ‘brain drain’ if the professional whites felt they didn’t belong in an ANC-led South Africa (tempting as it must have been to say “just let them leave”, the fact is that any modern state requires educated people, and the whites had preserved for themselves a near-monopoly on education). Plus of course, the sudden disappearance of the liberation movement’s major state-level backers (the USSR and the socialist countries of Eastern Europe) meant that the new South Africa had no real choice but to look to the west for development investment – a situation that has thankfully now changed with the rise of China and the BRICS bloc. Some of the complexities of the negotiation process are described in the following passage:

During negotiations, representatives of the previous order sought an outcome that would leave many elements of the apartheid system intact. On the other hand, the liberation movement sued for democratic majority rule as understood throughout the world. The transitional measures were seen by the liberation movement as necessary compromises to ensure the broadest possible legitimacy of the new order and to use the advances made as a beach-head to a truly united, non-racial, non-sexist, democratic and prosperous society. At the point of change of government in 1994, the state was manned at all senior levels by apartheid functionaries; the economy was almost totally in the hands of whites; many of the parties sought constitutional outcomes that would guarantee white privilege; and networks of apartheid and extreme right-wing destabilisation remained burrowed, or had multiple links, within the state. These and other realities impacted on the manner in which the programmes of change were introduced.

The fact is the local and international conditions did not exist for a quick transfer to socialism. Joe Slovo commented as early as 1987 – three years before the unbanning of the ANC – that “it is not possible to transform South Africa into a socialist country overnight”.

This [the projected post-apartheid society] is, of course, not a socialist society. It rather is a society that starts correcting the historic injustices and discrimination against blacks, thus creating the foundation and further conditions for a socialist South Africa. Therefore we are of the opinion that the shortest way to socialism in South Africa is that of non-racist democracy in which the people really have a say. However, this will still be a long way. No matter what vision one has of South Africa, the first thing that must be done is to destroy racism. Therefore, we must not tolerate attempts that take discussions about the details of a post apartheid society as an excuse to avoid or distort this basic issue.

This remains a realistic analysis of the national democratic revolution: a more or less fragile class alliance of all forces opposed to apartheid – the economic, political, social and cultural legacy of which is still in the process of being dismantled. Twenty years later, the ANC’s updated Strategy and Tactics document resulting from the 2007 National Conference reiterated this path:

The main content of the National Democratic Revolution is the liberation of Africans in particular and Blacks in general from political and socio-economic bondage. It means uplifting the quality of life of all South Africans, especially the poor, the majority of whom are African and female. At the same time it has the effect of liberating the white community from the false ideology of racial superiority and the insecurity attached to oppressing others. The hierarchy of disadvantage suffered under apartheid will naturally inform the magnitude of impact of the programmes of change and the attention paid particularly to those who occupied the lowest rungs on the apartheid social ladder.

To successfully pursue any kind of progressive agenda in the circumstances required an extremely subtle and complex strategy, and a large dose of tactical compromise. Whilst acknowledging that there’s still a long way to go, it’s important to recognise the significant steps that have been taken along the road to justice.

Wiping out legal apartheid

Apartheid as an institutionalised system of white supremacy has been dismantled. Gone are the days when “a black man with a BA was expected to scrape before a white man with a primary school education” (Long Walk to Freedom). Where there were pass laws, now there is freedom for all to come and go as they please. Where there was legally enforced segregation, now people are free to associate with whomever they choose. Where there were bantustans, now there is a vision for a united national identity of all tribes and races. Where the state was set up to serve the interests of the white minority alone, now it is oriented towards creating a better life for the African masses. Where education was largely denied to the black population, now it is available for all. Where there was deep repression of all political activity deemed to be ‘subversive’ (i.e. favouring equality), now people have full democratic rights. Where the working class had very limited labour rights, now workers’ unions are part of the government. As comrade Mandela said: “the principal result of our revolution, the displacement of the apartheid political order by a democratic system, has become an established fact of South African society”.

This wiping out of legal/political apartheid is no small accomplishment. When people assert that the modern South Africa is “worse than apartheid“, they downplay a particularly evil form of oppression, and they trivialise the historic achievements made in overturning minority rule. The continuing denial of basic human rights and national self-determination to the Palestinian people should remind us that there was nothing inevitable about the end of apartheid. To break minority rule; to defeat the whites’ demands for a permanent parliamentary veto; to avoid civil war, military intervention, balkanisation, power vacuum and economic anarchy – these were all remarkable achievements.

Orienting the state toward the needs of the oppressed

It has become popular among parts of the left (especially in the west) to describe the ANC as having capitulated to neoliberalism. The ANC, on the other hand, considers itself as a “disciplined force of the left, organised to conduct consistent struggle in pursuit of a caring society in which the well-being of the poor receives focussed and consistent attention. In terms of current political discourse, what it seeks to put in place approximates, in many respects, a combination of the best elements of a developmental state and social democracy. In this regard, the ANC contrasts its own positions with those of: national liberation struggles which stalled at the stage of formal political independence and achieved little in terms of changing colonial production relations and social conditions of the poor; neoliberalism which worships the market above all else and advocates rampant unregulated capitalism and a minimalist approach to the role of the state and the public sphere in general; and ultra-leftism which advocates voluntaristic adventures including dangerous leaps towards a classless society ignoring the objective tasks in a national democratic revolution.”

Which view is more accurate? It’s certainly true that multinational corporations have a major stake in the South African economy, and that the government has been keen to present the country as being ‘investor-friendly’. Furthermore, the figures for unemployment and inequality are intimidatingly high. As President Zuma himself points out, “our country still faces the triple challenge of poverty, inequality and unemployment, which we continue to grapple with”.

However, as prominent South African economist Haroon Bhorat notes, “these numbers belie the efforts of a benevolent state, which has used substantial fiscal revenue to expand social assistance. Currently, over a quarter of all South Africans receive government welfare checks, constituting 3 percent of the country’s gross domestic product… The share of South Africans with access to formal housing (77 percent), electricity (84 percent) and running water (72 percent) has increased drastically since 1994.”

In a recent interview, Blade Nzimande sums up the achievements of recent years, contrasting them with the picture of doom and gloom promoted by the (still predominantly white-owned) media:

They present South Africa as if it is falling apart. But over the last five years alone we have seen enormous gains for ordinary South Africans. Life expectancy has risen by four years, now averaging at 61. We’ve completely turned around the Aids denialism that was such a problem only recently. Improvements in education have been very impressive. Last year 78.2 per cent of school-leavers passed their final exams. It was less than 60 per cent in 1994. Sixty per cent of university students are now black or women. The government is also investing in a new health insurance scheme that will ensure everyone in the country gets coverage, and we’ve cleaned up the water supply, so over 80 per cent now have clean drinking water. We’re investing in our children. Of 12 million schoolchildren in South Africa, nine million receive a free school meal each day. The country is absolutely loyal to the ideals of the anti-apartheid movement.”

The increase in life expectancy – due largely to the “industrial scale distribution of antiretroviral drugs by the public health sector” – has been described by Professor Salim Abdool Karim, president of the South African Medical Research Council, as being “of the order usually only seen after a major societal shift, such as the abolition of slavery”. Mother-baby HIV transmission rate has decreased from 8.5% in 2008 to 2.7% in 2011.

The youth literacy rate is now around 98%, and the overall literacy rate is 87% – up from 70.1% in 2001, and the third highest in Africa. The number of black South Africans graduating from the country’s universities has increased more than fourfold in the past 20 years. The number of new teacher graduates doubled from 6,000 in 2009 to 13,000 in 2012.

Even the New York Times admits that, “since the end of apartheid, the government has built well over two million homes, brought electricity to millions of households and vastly increased the number of poor people with access to potable water. The average annual incomes of black-led households almost tripled from 2001 to 2011, according to census figures released late last year, and a growing percentage of the adult black population has gone to high school, with an increasing sliver going to college.”

South African author Jonny Steinberg notes that “84% South Africans now have electric lighting compared to 58% in 1996, while 85% of five and six year olds were attending school, compared to 35% 15 years ago. The poorest have benefited the most. All the extra things they are receiving now come directly from government. The ANC has built 1.8 million houses and given them away for free – it has literally changed the spaces in which they live. This is unprecedented anywhere in world.”

Efforts to diversify and industrialise are starting to yield results. For example, the government has promised that within the next five years, it will be able to procure at least 75% of its goods and services from South African producers. In spite of the global recession, South Africa’s economy has grown at a fairly steady 3.2% from 1994, and has experienced negative growth in only three out of 73 quarters.

Unemployment remains a massive problem – one inherited from an apartheid economy that didn’t even attempt to incorporate skilled black labour. The issue is compounded by the changes in the global economy towards digitalisation, and by the economic crisis. While the government is working to create jobs via its massive infrastructure programmes, it has put an extensive social welfare system in place. The number of South Africans receiving social grants has risen from 2.4 million to 16.1 million.

South Africa is unquestionably a better place to live than it was in 1994, but its achievements do not constitute long-term economic justice. The SACP is correct to point out that the “major socio-economic gains have been made ‘against the flow’ of the dominant growth trajectory; they are the result of government-led efforts and (to a lesser extent) of popular struggles. They have been largely based on efforts of reform and redistribution at the margins – a redistributive politics of ‘delivery’ out of surplus without fundamentally transforming the productive economy itself.”

In short, capitalism remains in place – not because the government favours capitalism but because to completely alienate capitalist class interests at the present moment would be to put the national democratic revolution at serious risk. Such a situation of a mainly capitalist economy administered by a progressive, socialist-oriented government is similar to the prevailing political economy in Brazil, Ecuador, Argentina and elsewhere. It certainly has its limitations, but it has been proven to be capable of delivering tangible benefit to the poorest sections of society. By no reasonable definition can it be considered ‘neoliberalism’.

The progressive family of nations

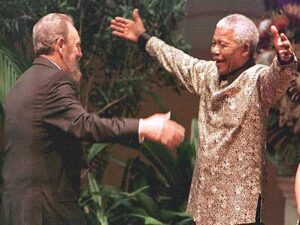

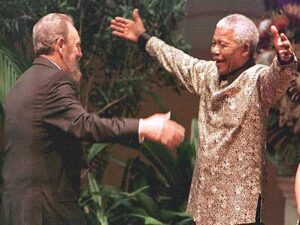

The west was hopeful that post-apartheid South Africa would exist within NATO’s sphere of influence and would be a dependable regional ally to imperialism, as it was under apartheid. These hopes were quickly frustrated. In spite of tremendous pressure to break his links with ‘undemocratic’ states and ‘terrorist’ groups, Mandela resolutely refused to turn his back on those who had rendered profound support to the South African liberation movement. During a trip to the US just a few months after his release from prison, Mandela was asked by Kenneth Adelman, former director of the US Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, why he was on such good terms with “supporters of international terrorism” such as Yasser Arafat, Fidel Castro and Muammar Gaddafi. Mandela replied without hesitation:

The west was hopeful that post-apartheid South Africa would exist within NATO’s sphere of influence and would be a dependable regional ally to imperialism, as it was under apartheid. These hopes were quickly frustrated. In spite of tremendous pressure to break his links with ‘undemocratic’ states and ‘terrorist’ groups, Mandela resolutely refused to turn his back on those who had rendered profound support to the South African liberation movement. During a trip to the US just a few months after his release from prison, Mandela was asked by Kenneth Adelman, former director of the US Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, why he was on such good terms with “supporters of international terrorism” such as Yasser Arafat, Fidel Castro and Muammar Gaddafi. Mandela replied without hesitation:

Yasser Arafat, Colonel Gaddafi, Fidel Castro support our struggle to the hilt. There is no reason whatsoever why we should have any hesitation about their commitment to human rights in South Africa. They are placing resources at our disposal to win the struggle.

Mandela’s attitude on this question did not change once in power. In 1997, presenting Gaddafi with South Africa’s prestigious Order of Good Hope, Mandela declared: “Those who feel we should have no relations with Gaddafi have no morals… Those who feel irritated by our friendship with President Gaddafi can go jump in the pool.”

Socialist Cuba remained a major inspiration for Mandela, and the South African government maintains excellent relations with Cuba to this day. South Africa remains a strong supporter of the Palestinian struggle for self-determination, and the boycott of Israel is official ANC policy.

Even well into old age, Mandela remained unquestionably on the right side of the global barricades – “a friend to those engaged in the struggle for justice across the globe”, to use the words of Gerry Adams, another great freedom fighter and part of the guard of honour at Mandela’s funeral. Speaking at the International Women’s Forum in Johannesburg in February 2003, Mandela delivered a scathing attack on the west’s plans for war against Iraq:

“Both Bush as well as Tony Blair are undermining an idea [of UN multilateralism] that was sponsored by their predecessors. They do not care. Is it because this Secretary General of the United Nations is now a black man [Kofi Annan]? They never did that when secretary generals were white… If there is a country that has committed unspeakable atrocities in the world, it is the United States of America… What I’m condemning is that one power with a president who has no foresight, who cannot think properly, is now wanting to plunge the world into a holocaust. All that he wants is Iraqi oil.

South Africa’s political/military role in the region – and further afield – has been completely transformed. The apartheid state was a bulwark of reaction, creating havoc in Angola and Mozambique, colonising Namibia (then South West Africa) and propping up the racist Ian Smith regime in Zimbabwe (then Southern Rhodesia). It was a reliable friend of Israel, and was only happy to do the dirty work of the CIA in southern Africa.

Modern South Africa on the other hand plays a positive role as part of the Southern African Development Community, engaging usefully in the Central African Republic, Mozambique and the Democratic Republic of Congo. It has refused to allow itself to be used as a battering ram against Zimbabwe, and has given protection and asylum to Haiti’s exiled anti-imperialist president, Jean-Bertrand Aristide.

As Abayomi Azikiwe writes in his excellent tribute to Mandela: “Under Mandela, South Africa would serve as an example to all oppressed and struggling peoples throughout the world. The country continues today to be in solidarity with the liberation movement of the Palestinians and the people of the Western Sahara, and maintains positions in support of African unity and economic integration.”

Although it made a bad error in voting for the no-fly zone against Libya, the Zuma administration went on to lead African Union efforts to negotiate a ceasefire (efforts which sadly failed due to the intransigence of the criminal NATO invaders).

China is now South Africa’s biggest trading partner by far, and South Africa joining the BRIC group of Brazil, Russia, India and China placed it firmly within the leadership of an emerging Global South, based on multipolarity and south-south cooperation. This network – “the progressive family of nations” – is starting to slowly break US global hegemony and is opening up a space in which countries can develop freely in a supportive global context.

Maintain unity in the struggle to build a new South Africa and defeat internal and external enemies

“Unity is fundamental for us, particularly to the achievement of the goals of the Freedom Charter. Divisions are a luxury we cannot afford. They do not belong to us and will not serve our people, but the enemy and his agents.” (source)

As outlined above, impressive progress has been made towards a just, prosperous, united South Africa. Nonetheless, vast problems remain, and many people are frustrated with the rate of progress. Unemployment is unacceptably high. The power of the multinationals has not been broken, and the redistribution of wealth is still in its very early stages (“the reality is that colonial relations in some centres of power, especially the economy, remain largely unchanged”). Enormous inequality persists, and this is still closely correlated with the race question (as Zuma points out: “All reports point to the fact that white males are still in control of the means of the production”). The land reform process has barely begun. The streets are still violent, and corruption is a major issue (although it seems progress is being made on this score).

In short, the national democratic revolution is still incomplete. This fact is clearly recognised by the ANC itself:

Steadily, the dark night of white minority political domination is receding into a distant memory. Yet we are only at the beginning of a long journey to a truly united, democratic and prosperous South Africa in which the value of all citizens is measured by their humanity, without regard to race, gender and social status.

Land reform, job creation, increased industrialisation and wealth redistribution are the key tasks of the coming period, along with continuing the work at a regional and global level to create more favourable circumstances for socialist development. It is time for a “radical socio-economic transformation to meaningfully address poverty, unemployment and inequality”. What political organisation is fit to take the lead in these tasks?

Many loud voices on the left are arguing that the ANC is past its sell-by date. Combined with the voices on the right – that have never stopped denigrating the ANC – we’re left with a loud chorus singing its anti-ANC hymn. With a ‘free’ press that is dominated by big (white) capital, this hymn gets broadcast to the masses constantly via newspaper, internet and TV. Although the chorus is louder than before, it is by no means a new phenomenon. Mandela identified it back in 1997:

The prophets of doom have reemerged in our country. In 1994, these predicted that the transition to democracy would be attended by a lot of bloodshed. Disappointed in their expectations by what actually happened, they nevertheless never abandoned their resolve to spread despair. The pivot of their offensive is that the history of Africa is a history of failure and disaster. Accordingly, they adhere to the openly racist position that a South Africa led by the African National Congress and no longer under white minority rule, will, inevitably sink into failure and disaster. And so they go about their business to highlight and elevate anything that is negative. Neither do they hesitate to tell lies or to invent stories so long as this advances their purposes… They advance this agenda of gloom and doom on which the enemies of real progress and social transformation rely to create the conditions for the defeat of the ANC, so that they are better able to ensure that no progress and no transformation occur…

They [the white opposition] believe that their fortunes lie not so much in policies they can propagate, but in their success in projecting themselves as tireless fighters for the defeat of the ANC. Their task is to spread messages about an impending economic collapse, escalating corruption in the public service, rampant and uncontrollable crime, a massive loss of skills through white emigration and mass demoralisation among the people either because they are white and therefore threatened by the ANC and its policies which favour black people, or because they are black and consequently forgotten because the ANC is too busy protecting white privilege.

Is this not reminiscent of the current media onslaught against the ANC and SACP – a campaign which is enthusiastically taken up by the mainstream press in the imperialist countries? Although the ANC has ‘played ball’ to an extent, it is by no means the preferred choice of international capital. Its liberation struggle roots; its social base in the oppressed; its membership of BRICS; its strong relations with ‘pariah’ states such as Cuba, Zimbabwe and the DPRK; its leadership role within Africa: all these things and more make the west decidedly uncomfortable. There are very few things the US and European ruling classes would like more than to see the ‘Democratic Alliance’ apartheid-nostalgia-brigade come to power in South Africa, and the barrage of left-sounding critiques of Mandela being printed in the mainstream press (such as that by Slavoj Žižek) is in support of that aim.

In such a context, and in the complete absence of any serious contender for leadership of the South African masses, unity is absolutely critical to prevent the forces of reaction from regaining the upper hand. The lessons of history are there to be learned. As Mandela warned: “Besides the advanced productive forces at the disposal of the colonial powers, one of the central reasons for the defeat of indigenous communities was division and conflict among these communities themselves”

The defenders of apartheid privilege continue to sustain a conviction that an opportunity will emerge in future, when they can activate this counter-insurgency machinery, to impose an agenda on South African society which would limit the possibilities of the democratic order to such an extent that it would not be able to create a society of equality, that would be rid of the legacy of apartheid. Accordingly, various elements of the former ruling group have been working to establish a network which would launch or intensify a campaign of destablisation, some of whose features would be: the weakening of the ANC and its allies; the use of crime to render the country ungovernable; the subversion of the economy; and the erosion of the confidence of both our people and the rest of the world in our capacity both to govern and to achieve our goals of reconstruction and development. This counter-revolutionary network, which is already active and bases itself on those in the public administration and others in other sectors of our society who have not accepted the reality of majority rule, is capable of carrying out very disruptive actions. It measures its own success by the extent to which it manages to weaken the democratic order.

Numerous alternatives to the ANC have been – and are being – set up. But can they play a progressive role when the only unity they promote is an unprincipled unity with tribalist conservative demagogues against the mainstream of the liberation movement as represented by the ANC, Cosatu (the Congress of South African Trade Unions) and the SACP?

None of this is said in order to deny, or make light of, the problems, contradictions and differences within the ANC. The issues of cronyism, corruption, bureaucracy are real and understood (such problems are of course not unique to South Africa, and can be found in progressive and reactionary states alike). And the ANC continues to comprise a broad range of class interests, which exist in a sometimes uneasy coexistence. These problems are perfectly well understood within the organisation: “Patronage, arrogance of power, bureaucratic indifference, corruption and other ills arise, undermining the lofty core values of the organisation: to serve the people! How the ANC negotiates this minefield will determine its future survival as a principled leader of the process of fundamental change, an organisation respected and cherished by the mass of the people for what it represents and how it conducts itself in actual practice.”

But breaking up the leadership of a national democratic revolution that has been in place for over a hundred years is not something to take lightly. Certainly there’s no indication that Mandela would ever have advocated a break with the ANC. Apart from anything else, he left the organisation a significant portion of his estate! Mandela was a party man. Stepping down as party leader at the ANC conference in December 1998, he said: “A name becomes the symbol of an era. As we hand over the baton it is appropriate that I should thank the ANC for shaping me as a symbol of what it stands for. I know that the love and respect that I have enjoyed is love and respect for the ANC and its ideals.” Attempts to justify splits and spin-off organisations on the basis of “upholding Madiba’s legacy” are utterly disingenuous.

The only realistic path for those wishing to push South Africa in a more progressive direction is to work within the mainstream of the liberation movement to do just that. This is precisely what Cosatu and the SACP do, and it parallels the work of communists within the Brazilian government, or Marxists within Sinn Féin. If the left abandons the mainstream of the struggle, it means “surrendering the leadership of the national struggle to the upper and middle strata.” Who does that help? Not the South African masses, but international capital.

Chris Hani, a few weeks before his untimely death, predicted this new phase with eerie precision.

Chris Hani, a few weeks before his untimely death, predicted this new phase with eerie precision.

I think finally the ANC will have to fight a new enemy. That enemy would be another struggle to make freedom and democracy worthwhile to ordinary South Africans. Our biggest enemy would be what we do in the field of socio-economic restructuring. Creation of jobs; building houses, schools, medical facilities; overhauling our education; eliminating illiteracy, building a society which cares, and fighting corruption and moving into the gravy train of using power, government position to enrich individuals. We must build a different culture in this country… and that culture should be one of service to the people.

Celebrating the legacy of Nelson Mandela and Chris Hani means to protect the unity they worked so hard to create; to complete the revolution that they did so much to further; to build and improve the organisations they served so selflessly; to serve the people of South Africa; to finish the work of building a new society and undoing the damage of three and a half centuries of ruthless, racist oppression.

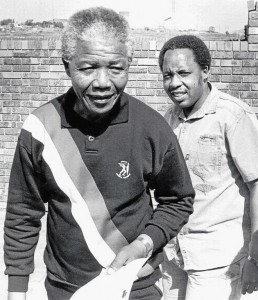

In April 1990, Hani was able to return to South Africa on a provisional amnesty order from the white government, as it inched towards a negotiated settlement. He immediately began working tirelessly, travelling the country to educate people about the political process taking place and also to raise their socialist consciousness. He was everywhere received with undisguised joy, perhaps second only to Nelson Mandela in popularity.

In April 1990, Hani was able to return to South Africa on a provisional amnesty order from the white government, as it inched towards a negotiated settlement. He immediately began working tirelessly, travelling the country to educate people about the political process taking place and also to raise their socialist consciousness. He was everywhere received with undisguised joy, perhaps second only to Nelson Mandela in popularity. One important – and controversial – issue related to the life of Chris Hani is the relationship between the struggle for socialism and the struggle for national liberation; and more specifically, between the ANC and the SACP. This relationship has been under almost constant attack from the 1930s onwards. The apartheid regime and its western imperialist backers used the relationship to ‘prove’ that the anti-apartheid struggle was simply part of an evil Soviet plot against western-style freedom and democracy. Meanwhile, there were plenty of people within the anti-apartheid camp who opposed the relationship on the basis that the SACP was allegedly white-dominated and that Marxism was an imported ideology that was not relevant for Africans.

One important – and controversial – issue related to the life of Chris Hani is the relationship between the struggle for socialism and the struggle for national liberation; and more specifically, between the ANC and the SACP. This relationship has been under almost constant attack from the 1930s onwards. The apartheid regime and its western imperialist backers used the relationship to ‘prove’ that the anti-apartheid struggle was simply part of an evil Soviet plot against western-style freedom and democracy. Meanwhile, there were plenty of people within the anti-apartheid camp who opposed the relationship on the basis that the SACP was allegedly white-dominated and that Marxism was an imported ideology that was not relevant for Africans. Chris Hani was murdered on 10 April 1993 in Johannesburg by a fascist gunman by the name of Janusz Waluś, who was working with a senior Conservative Party MP on a plot to assassinate a number of prominent liberation fighters and thereby spark a civil war along race lines, derailing the negotiations to end apartheid. Their plot was unsuccessful, as the massive wave of shock and grief at Hani’s death was channelled towards a new momentum in the peace process. South Africa’s first democratic election – one of the most historic events of the twentieth century – took place a year later, on 27 April 1994.

Chris Hani was murdered on 10 April 1993 in Johannesburg by a fascist gunman by the name of Janusz Waluś, who was working with a senior Conservative Party MP on a plot to assassinate a number of prominent liberation fighters and thereby spark a civil war along race lines, derailing the negotiations to end apartheid. Their plot was unsuccessful, as the massive wave of shock and grief at Hani’s death was channelled towards a new momentum in the peace process. South Africa’s first democratic election – one of the most historic events of the twentieth century – took place a year later, on 27 April 1994.