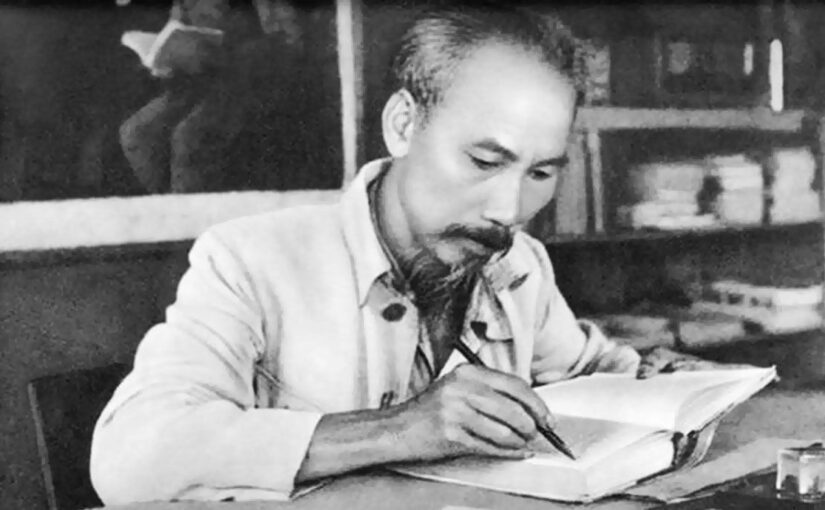

“They may bring in half a million, a million or even more troops to step up their war of aggression in South Vietnam. They may use thousands of aircraft for intensified attacks against North Vietnam. But never will they be able to break the iron will of the heroic Vietnamese people, their determination to fight against American aggression, for national salvation. The more truculent they grow, the more serious their crimes. They war may last five, ten, twenty or more years; Hanoi, Haiphong and other cities and enterprises may be destroyed; but the Vietnamese people will not be intimidated! Nothing is more precious than independence and freedom. Once victory is won, our people will rebuild their country and make it even more prosperous and beautiful.” (Ho Chi Minh, Appeal to compatriots and fighters throughout the country, July 17, 1966)

Forty years ago, on the 29th of April 1975, the joint forces of the North Vietnamese Army and the National Liberation Front entered the southern capital of Saigon, where they were greeted with the open joy of a population which had endured untold misery over the course of decades at the hands of foreign invaders and puppet governments. Just a day later, at around 10:45am, a North Vietnamese tank crashed through the gates of the presidential palace and raised the red flag. The head of the collapsing South Vietnamese regime, Duong Van Minh, reportedly told North Vietnamese colonel, Bùi Tín, “I have been waiting since early this morning to transfer power to you,” to which Bùi Tín replied: “There is no question of your transferring power. Your power has crumbled. You cannot give up what you do not have.”

Forty years ago, on the 29th of April 1975, the joint forces of the North Vietnamese Army and the National Liberation Front entered the southern capital of Saigon, where they were greeted with the open joy of a population which had endured untold misery over the course of decades at the hands of foreign invaders and puppet governments. Just a day later, at around 10:45am, a North Vietnamese tank crashed through the gates of the presidential palace and raised the red flag. The head of the collapsing South Vietnamese regime, Duong Van Minh, reportedly told North Vietnamese colonel, Bùi Tín, “I have been waiting since early this morning to transfer power to you,” to which Bùi Tín replied: “There is no question of your transferring power. Your power has crumbled. You cannot give up what you do not have.”

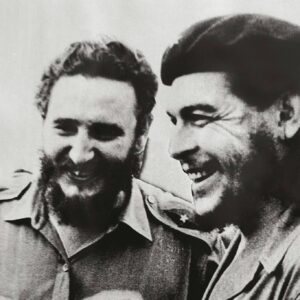

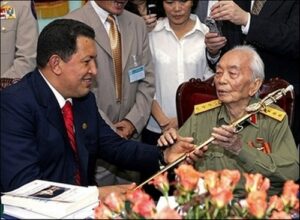

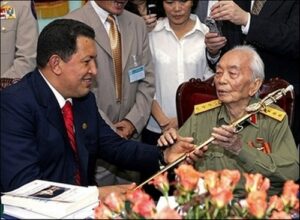

In the words of Fidel Castro, it was “one of the greatest events in modern history”.

Meanwhile, what was left of the US military and diplomatic staff in Saigon was hurriedly (ignominiously, you could say) airlifted out of the country, in what remains the biggest helicopter rescue operation of all time (7,000 people in two days).

In the course of just a few months, the revolutionary forces’ Spring Offensive had succeeded in occupying the whole of the country, finally bringing an end to the Vietnam War, and closing the 90-year chapter of colonial domination and division of their country. The Vietnamese became the first people in history to deal an outright defeat to the world’s biggest imperialist power: the United States of America. This incredible achievement was the culmination of decades of heroic and brilliant struggle.

“Our entire country resisted for thirty years, and those years trained us as people, trained our soldiers, and gave us much precious experience. The victory of the August Revolution established conditions for our victorious resistance against the French. The victorious resistance against France created conditions for us to build the North into a firm revolutionary base for the whole country to defeat the United States. When we chased the American troops out, it finally created conditions for us to topple the puppets.” (Van Tien Dung – Our Great Spring Victory)

This article will give a basic outline of the history of the war, as well as exploring some ideas as to how Vietnam – a small, poor, Southeast Asian country – came to defeat the most aggressive, most militarised imperialist power of all time.

The long struggle for independence and freedom

French colonialism

Western colonialism first came to Vietnam in the mid-19th century when, in 1858, a French naval squadron attacked the port city of Da Nang, on the central coast. This attack, the supposed purpose of which was to protect Christian missionaries operating in the area, quickly turned into a war of conquest. By 1887, France had political control of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos, which it ruled collectively as French Indochina. The name ‘Vietnam’ was declared extinct in 1883, and its territory was broken up into three separate entities: Tonkin (the northernmost province, incorporating Hanoi and bordering China), Annam (the long central strip, incorporating Da Nang and the old capital Hue), and Cochin China (the southernmost province, incorporating Saigon). Tonkin and Annam were French protectorates; Cochin China – the area blessed with the greatest natural wealth – was a full colony.

Like most colonial occupations, the French presence in the region was driven by economics – Indochina offered rice, rubber and cheap labour. In the world wars, Indochina was also forced to provide hundreds of thousands of military-age men as cannon-fodder.

In alliance with the local feudal class, the French colonialists succeeded in destroying the centuries-old land ownership system, thereby causing dire poverty and widespread famine. Ngo Vinh Long notes that: “As soon as the French occupied a certain area after fierce struggles with the local populace, they confiscated the land belonging to the locals and gave it to themselves and their Vietnamese collaborators. Tens of thousands of acres of peasants’ lands changed hands this way… Rice exporting was the biggest and most profitable way of making money for the French and the Vietnamese ruling class. By the 1920s and 1930s over half of the peasants in Tonkin and Annam were completely landless, and about 90 percent of those who owned any land owned next to nothing.” (‘Coming to Terms: Indochina, the United States, and the War’)

An inevitable side-effect of this mass theft was the creation of a rural working class: large numbers of peasants who, deprived of their land, had no choice but to work as agricultural labourers or sharecroppers, or to move to the cities in order to join the ranks of the industrial working class. It was these landless and propertyless Vietnamese who would come to form the mass base of a resistance movement that would successfully expel the French, and would later defeat the armed might of the United States of America.

The exploitation was ruthless and vindictive. Starvation in the countryside became the normal state of affairs. Vietnamese agronomist Nghiem Xuan Yem wrote in 1945: “All through the sixty years of French colonisation our people have always been hungry. They were not hungry to the degree that they had to starve in such manners that their corpses were thrown up in piles as they are now. But they have always been hungry, so hungry that their bodies were scrawny and stunted; so hungry that no sooner had they finished with one meal than they started worrying about the next; and so hungry that the whole population had not a moment of free time to think of anything besides the problem of survival.” (cited in Ngo Vinh Long, op cit)

Conditions in the cities were not much better. Vietnamese men, women and children laboured in factory conditions that make Britain’s famously brutal industrial revolution look like a picnic. “In the mines and rubber plantations workers were frequently severely punished for even the slightest ‘infractions’ and hence they called these places ‘hell on earth’. Few escaped from that hell. The usual punishment for workers who ran away was death by torture, hanging, stabbing, or some other means that made examples of the ‘criminals’. Because of this – and overwork, inadequate food, and terrible housing – the mortality rate was about 30 percent, according to the rubber companies’ own records.” (ibid) Furthermore, Vietnamese were denied the right to education – it was estimated that, in 1945, 90 percent of the population was illiterate. So much for France’s ‘mission civilisatrice’ (civilising mission).

National resistance

Oppression breeds resistance, and the Vietnamese people resisted the French occupation from the beginning. Marilyn Young, in her extremely useful book ‘The Vietnam Wars’, notes that, for the entire period of French occupation, “Vietnamese struggled against French rule in sporadic uprisings that sometimes achieved the intensity of full-scale guerrilla warfare.”

Oppression breeds resistance, and the Vietnamese people resisted the French occupation from the beginning. Marilyn Young, in her extremely useful book ‘The Vietnam Wars’, notes that, for the entire period of French occupation, “Vietnamese struggled against French rule in sporadic uprisings that sometimes achieved the intensity of full-scale guerrilla warfare.”

For the first few decades of French colonisation, the Vietnamese resistance was disunited and disparate; although heroic and on occasion spectacular, it failed to unite and engage the masses of the population, and was therefore relatively easy for the colonial authorities to suppress. However, with the victory of the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the establishment shortly after of the Communist International (a coalition of communist parties designed to give guidance and support for revolutionary movements around the world), new avenues opened up for many liberation movements in Asia and Africa.

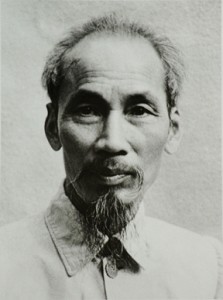

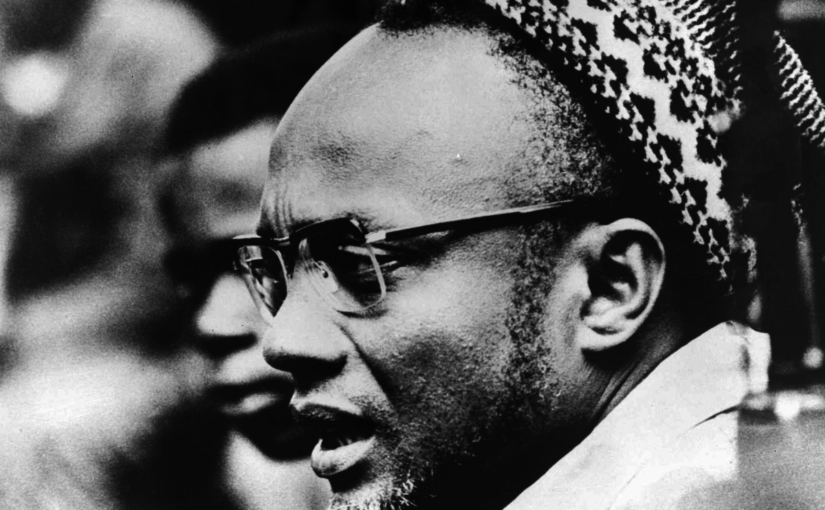

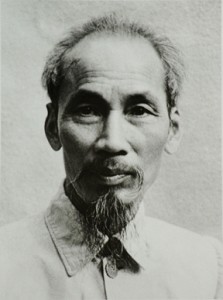

Global anti-imperialism was a key part of the young Soviet state’s ethos, and the extension of Marxist philosophy and political economy to the oppressed nations remains one of Lenin’s most important contributions to revolutionary science. Without so much as a hint of chauvinism, Lenin proved that, in the age of imperialism, the liberatory ideas expressed in the Communist Manifesto had become relevant not just to the working class of Europe but also to the oppressed and downtrodden people of the entire world. Ho Chi Minh was one of the first to recognise the full significance of this, writing, shortly after Lenin’s death:

“Lenin laid the basis for a new and truly revolutionary era in the colonies. He was the first to denounce resolutely all the prejudices which still persisted in the minds of many European and American revolutionaries… He was the first to realise and assess the full importance of drawing the colonial peoples into the revolutionary movement. He was the first to point out that, without the participation of the colonial peoples, the socialist revolution could not come about… Lenin’s strategy on this question has been applied by communist parties all over the world, and has won over the best and most active elements in the colonies to the communist movement.” (Lenin and the Colonial Peoples, 1925)

The establishment of a socialist base had a dramatic effect on the global struggle against colonialism. In increasingly large numbers, the representatives of these movements came to the Soviet Union to see the transformations taking place, to learn from the Soviets’ experience, and to get political education and military training. The Communist University of the Toilers of the East, set up by the Comintern in 1921, trained leading liberation fighters from Vietnam, China, Indonesia, Greece, South Africa, Iraq, Syria and elsewhere. Its alumni include Ho Chi Minh and other prominent Vietnamese radicals.

On 3 February 1930, at a meeting in Kowloon (China) convened by Nguyen Ai Quoc (the famous Vietnamese revolutionary later to be known as Ho Chi Minh), the Indochinese Communist Party was formed, uniting the three existing parties of the Vietnamese left. The meeting agreed a ten-point programme calling for the complete overthrow of French imperialism, an end to Vietnamese feudalism, the confiscation of land from the colonisers and big landowners and its distribution to poor peasants, an eight-hour working day, universal education, and equality between men and women.

As Naomi Cohen notes, “this was a revolutionary program to fundamentally change the property relations in society. It gave the Vietnamese people the political confidence, backed up by a strong, centralised organisation, to take up arms against the French and begin the long struggle for liberation.” The party’s programme and energetic activity quickly won the support of large numbers of Vietnamese, and it “soon emerged as the undisputed leader of the Vietnamese revolution,” organising “massive peasant demonstrations and workers’ strikes in most parts of the country” (Ngo Vinh Long, op cit).

Within a year, a series of insurrections led to the creation of the Nghe Tinh soviet in two provinces of central Vietnam, Nghe An and Ha Tinh. “For several months peasant associations and unions, often led by Communist cadres, abolished taxes, shortened the work day, distributed confiscated land, conducted literacy classes, administered justice — in short, they ruled themselves” (Young). The French military eventually brought this experiment to an end the best way they knew how: with brutal and excessive firepower. A local French newspaper commented: “Corporal punishment, tortures, brutal methods will teach the crowds cowardly enough to listen to the inciters of rebellion that we, too, are terrible in repression and that the last word will be ours.” (cited in Joseph Buttinger ‘Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled’).

The ICP continued to grow in experience and influence. “Thousands of party cells were formed all over the country, hundreds of organisations of all types were set up, and an average of five hundred demonstrations and strikes were staged every year. As a result, by the time World War II was about to begin, the revolutionary movement in Vietnam was already well prepared politically and organisationally, both in the towns and in the countryside.” (Ngo Vinh Long, op cit)

Meanwhile, the ripples of World War II were felt in Vietnam. In 1940, Japan occupied all of Indochina, which it then proceeded to rule in collaboration with the French Vichy administration – the stooge French government propped up by Nazi Germany. The Viet Minh (League for the Independence of Vietnam) was formed a year later by the ICP as an anti-imperialist front to unite all forces, communist and nationalist, in a single fighting organisation able to rid the country of the colonial occupiers from both east and west. By the end of World War II, the Viet Minh’s membership had grown to over half a million (out of a total population of less then 25 million).

It was around this time that Ho Chi Minh returned to Vietnam after three decades of exile, in order to take direct leadership of the liberation struggle – a fight for which he had been the principal strategist since the mid-1920s. The Viet Minh leadership based itself in the mountainous areas near the Chinese border, where they could relatively easily elude the colonial authorities, and make trips to China when necessary to coordinate with their comrades in the Chinese Communist Party. William Duiker, in his detailed biography of Ho Chi Minh, describes something of the hardships they faced: “To survive they were often forced to forage for food, such as corn, rice, or wild banana flowers. Despite the concerns of his colleagues, Nguyen Ai Quoc [Ho Chi Minh] insisted on sharing the deprivations with the rest. When spirits flagged or enthusiasm grew to excess, he counselled them: ‘Patience, calmness, and vigilance, those are the things that a revolutionary must never forget.’”

In spite of brutal repression, not to mention a policy of forced rice collection by the French authorities that caused an unprecedented famine (it led to two million deaths in Tonkin – a full quarter of the population), the Viet Minh continued to expand its activities, including the establishment of hundreds of guerrilla bases and raids on French and Japanese rice stores.

August Revolution

In March 1945, Japan unilaterally ended French rule in Indochina and established a nominally independent Vietnam under Emperor Bao Dai, who had until then been king of the Annam (central Vietnam) protectorate. With the axis collapsing, the Potsdam Conference of soon-to-be victors in World War II agreed that Vietnam would be temporarily separated, with the Chinese Nationalists (Kuomintang) taking control of the northern part and Britain taking control of the south.

Needless to say, the Viet Minh had different ideas, rapidly expanding its base in the far north and setting up a large liberated zone in the rural areas. In this territory, “entirely new local governments were established, self-defence forces recruited, taxes abolished, rents reduced and, in some places, land that had belonged to French landlords was seized and redistributed. Above all, the Viet Minh acted to alleviate the famine then raging, by opening local granaries and distributing the rice.” (Young).

With the Japanese surrender on 15 August, the revolutionary forces moved quickly to fill the power vacuum, launching what came to be known as the August Revolution. “As soon as the order for general insurrection was issued, people’s organisations and guerrilla and self-defence units everywhere moved into action. From 14 to 18 August the administration centres of almost every village, district and province of 27 provinces were attacked and taken over, and revolutionary power was established in many of them almost immediately. The administrations of the three major cities of Hanoi, Hue and Saigon held out a few days longer, but the victory of the Viet Minh was swift and bloodless… For the first time in the long history of Vietnam, the administration of the entire country was in the hands of the people.” (Ngo Vinh Long)

On 2 September, Ho Chi Minh read out the Declaration of Independence in the Ba Dinh square in Hanoi, to a crowd of over half a million ecstatic Vietnamese.

The French have fled, the Japanese have capitulated, Emperor Bao Dai has abdicated. Our people have broken the chains which for nearly a century have fettered them and have won independence for the Fatherland. Our people at the same time have overthrown the monarchic regime that has reigned supreme for dozens of centuries. In its place has been established the present Democratic Republic… The whole Vietnamese people, animated by a common purpose, are determined to fight to the bitter end against any attempt by the French colonialists to reconquer their country.

They didn’t have to wait too long for such an attempt by the French colonialists. The US, desperate to prevent Vietnam falling into the Soviet sphere and anxious to strengthen the capitalist forces in France itself, was adamant that Vietnam should remain in French hands. In late September, the French – using US-supplied weapons and backed by British troops – launched their war of reconquest.

With their massive superiority of firepower, the French were able to re-establish basic surface-level political power throughout the country. However, the Viet Minh retreated to the countryside, launching a guerrilla struggle that would allow the French no peace until the end of the war. “Resistance villages were built everywhere. French storage depots, strategic and economic centres, and communication lines were under constant attack. The war was even brought to the hearts of big cities such as Hanoi, Saigon, Hue and Haiphong, where the French had thought they were secure. Hand in hand with the guerrilla force, during the 1949-50 period the People’s Army launched a series of campaigns over the entire country, destroying more than 200 fortified positions, killing more than 10,000 colonial troops, and liberating large territories.” (Ngo Vinh Long)

Defeat for France

The victory of the Chinese Revolution in October 1949 provided a tremendous boost to the Vietnamese Revolution. Ho Chi Minh travelled to Beijing the next month to congratulate Mao Zedong and Ho’s old friends Zhou Enlai and Liu Shaoqi. A few weeks later, Beijing issued a declaration that China and Vietnam were together “on the front lines in the vanguard of the struggle against imperialism” (cited in Duiker). Shortly after, both China and the Soviet Union recognised the Democratic Republic of Vietnam – the government led by the Viet Minh – as the sole legitimate representative of the Vietnamese people. What’s more, the Viet Minh secured a steady supply of weaponry, and the assistance of dozens of battle-hardened Chinese military advisers (ironically, many of the weapons they received were North American: “Mao Zedong’s victory in China gave the Vietnamese not merely an ally but, for the first time, direct material aid. In addition to formal recognition, the Chinese shipped across the border a rich supply of American arms captured from Chinese Nationalist troops during the Chinese Civil War.” (Young))

The French were on their last legs. In March 1954, in a last-ditch attempt to reverse the tide of the war, they initiated an operation to insert a large number of soldiers at Dien Bien Phu, in the north-west of the country. The purpose of the operation was to cut off Viet Minh supply lines and draw the Viet Minh out of its guerrilla warfare comfort zone and into a major confrontation in which the French troops could make use of their superior military technology. They soon found out that they had badly underestimated the bravery and military brilliance of the Vietnamese.

Marilyn Young writes: “Through terrain the French had considered impassable, 200,000 peasants hacked trails and moved supplies as far as 500 miles to the battlefront. They laid hundreds of miles of roads. All through the North, women and men mobilised to transport dismantled howitzers and mortars (American in the main, captured by the Chinese in Korea), tons of ammunition, and rice by bicycle and shoulder pole. Troops and equipment, doubly camouflaged by jungle foliage which they attached to themselves and through which they moved, scattered whenever they heard the engines of the French planes searching for them. The combat troops, four divisions strong (49,000 men), carried their own weapons and food supply… Daily the column of porters and soldiers was strafed, bombed, napalmed; and daily they advanced.”

With everything in place, General Vo Nguyen Giap commenced the attack on 13 March. A few weeks later, on 7 May, the French surrendered. The Viet Minh had won its war against French colonialism – “the first time in history a small colony had defeated a big colonial power” (Ho Chi Minh). A BBC report acknowledges that, “in the history of decolonisation, [The Battle of Dien Bien Phu] was the only time a professional European army was decisively defeated in a pitched battle.”

Analysing the historic Dien Bien Phu victory some years later, Giap wrote:

“We established a great historic truth: a colonised and weak people, once it has risen up and is united in the struggle and determined to fight for its independence and peace, has the full power to defeat the strong aggressive army of an imperialist country. Thus, Dien Bien Phu was a victory not only for our people, but also for all weak peoples who are struggling to throw off the yoke of the colonialists and imperialists.” (Vo Nguyen Giap, People’s War People’s Army)

US imperialism takes over from French colonialism

Within days of the Vietnamese victory at Dien Bien Phu, the Geneva Conference (convened by the big powers to resolve outstanding issues related to Korea and Indochina) agreed a programme to formally end the conflict. The Geneva Accords mandated that France withdraw and that Vietnam be temporarily partitioned into the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (the north, ruled by the Viet Minh) and the State of Vietnam (the south, ruled by Bao Dai). Nationwide general elections would be held by July 1956, and these would result in the creation of a unified Vietnamese state.

At this point, the US started to seriously ramp up its involvement. A congressional study at the time made it only too clear what was at stake: “The area of Indochina is immensely wealthy in rice, rubber, coal and iron ore. Its position makes it a strategic key to the rest of Southeast Asia. If Indochina should fall, Thailand and Burma would be in extreme danger; Malaya, Singapore and even Indonesia would become more vulnerable to the communist drive… The communists must be prevented from achieving their objectives in Indochina.”

In the south, the US installed its puppet Ngo Dinh Diem as president, with clear instructions to do everything possible to prevent the scheduled elections and reunification from taking place. All parties, including the US government, were perfectly aware that the Viet Minh would win the national elections by a landslide and that this would quickly bring an unambiguous end to imperialist domination of the region. President Eisenhower acknowledged in his memoirs: “I have never talked or corresponded with a person knowledgeable in Indochinese affairs who did not agree that, had elections been held as of the time of the fighting, possibly 80 percent of the population would have voted for the Communist Ho Chi Minh” (cited in William Blum, ‘Killing Hope’). So it goes without saying that the US – the self-proclaimed global standard-bearer of democracy – would have to stop the elections from taking place at all costs.

Repression in the south, socialism in the north

While the north was preparing for reunification, the Diem government focused on organising large-scale repression and pacification. “The Diem regime moved, publicly as well as covertly, to eliminate or stifle all opposition. Despite the Geneva Agreements’ prohibition against political reprisal, it quickly targeted the most visible of large numbers of Viet Minh sympathisers in the South.” (George Kahin, ‘Intervention’)

Under Law 10/59, promulgated in May 1959, anyone found to be committing “crimes of sabotage, or infringing upon the security of the state”, or even indeed belonging “to an organisation designed to help or perpetrate these crimes” was to be given the death sentence. That most terrible of crimes, “spreading by any means unauthorised news about prices”, was also punishable by death. By 1963, “not a day passes without the US-Diemists terrorizing, mopping up, and killing people, burning down villages, spraying poisonous chemicals, destroying crops, forcing people into concentration camps, those hells on earth which they call ‘strategic hamlets’” (Ho Chi Minh, Address to the National Assembly, 8 May 1963).

Diem’s repression failed to eliminate the widespread popular demand for reunification. Much of the South Vietnamese countryside had been liberated territory during the war against the French, and the peasants had enjoyed the benefits of land reform and direct democracy. Added to this was the example of the north: while in the south Diem was busily handing land back to big landlords and murdering Viet Minh supporters, in the north the population was moving forward and building socialism.

Having secured its state in 1954, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was making remarkable progress. Agricultural production was significantly increased, as was industrialisation. Legal equality between men and women was established. Famine was defeated, and education was opened up to the masses for the first time. Ho Chi Minh reported in 1964 that ”95 per cent of the population have become literate while under French rule 95 per cent were illiterate… Alphabets have been designed for the languages of some minority peoples, and many young people from minority nationalities have graduated from our universities. Health work has recorded many achievements, many epidemics and old social diseases have been checked, the people’s health has been improved… Over the past ten years, the North has made big strides forward without precedent in our national history” (Report at the Special Political Conference, March 27, 1964).

Having secured its state in 1954, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was making remarkable progress. Agricultural production was significantly increased, as was industrialisation. Legal equality between men and women was established. Famine was defeated, and education was opened up to the masses for the first time. Ho Chi Minh reported in 1964 that ”95 per cent of the population have become literate while under French rule 95 per cent were illiterate… Alphabets have been designed for the languages of some minority peoples, and many young people from minority nationalities have graduated from our universities. Health work has recorded many achievements, many epidemics and old social diseases have been checked, the people’s health has been improved… Over the past ten years, the North has made big strides forward without precedent in our national history” (Report at the Special Political Conference, March 27, 1964).

The way that socialism manifested itself at the basic everyday level is described by a villager from a Central Highlands tribe: ”The living conditions of the people were getting better and better every day. The people were well off. They had enough to eat. They were able to attend school. They were free with no oppression from anyone. There were no imperialist foreigners in the North. They had land to work and buffaloes to help them plow the land. There were no more cruel landlords to lord it over them” (cited in Young).

A fascinating account by Noam Chomsky of his trip to North Vietnam in 1970 gives a vivid impression of what life was like. Visiting a village school, he writes: “We sat in a mathematics class (seventh grade, children of twelve to fourteen) for some time. There were forty-five children studying geometry. I looked through some of the children’s notebooks, which contained neatly done, quite advanced algebra problems. The lesson was lively. Children tried to work out proofs of theorems as the teacher sketched their proposals on the blackboard. The level was remarkably high, easily as advanced as anything I know of in the United States. It was particularly striking to find such work in a remote village, barely a generation removed from illiteracy.” He continues: “There is no doubt that the spirit of national independence and dignity is high, and that the Vietnamese are proceeding to lay the basis for a modern society.”

Chomsky quotes British journalist Richard Gott, who had also recently travelled to North Vietnam, summing up Vietnamese socialism: “By getting rid of the rich, and avoiding extremes of poverty, Vietnam gives the impression of a prospering, cohesive society, unique in the under-developed world.”

Birth of the National Liberation Front

The people of Vietnam, north and south of the 17th parallel, had assumed that they would win reunification and independence through the elections promised by the Geneva Accords. When it became clear that the US and its puppet Diem would never allow the elections to take place, and that Diem was stifling all opposition in order to create a permanent neocolonial state in South Vietnam, the resistance in the south was forced to formulate a new strategy. On 20 December 1959, several political and religious groups joined together into the National Liberation Front with a view to overthrowing Diem, establishing a coalition government, and setting Vietnam back on the road to reunification.

The people of Vietnam, north and south of the 17th parallel, had assumed that they would win reunification and independence through the elections promised by the Geneva Accords. When it became clear that the US and its puppet Diem would never allow the elections to take place, and that Diem was stifling all opposition in order to create a permanent neocolonial state in South Vietnam, the resistance in the south was forced to formulate a new strategy. On 20 December 1959, several political and religious groups joined together into the National Liberation Front with a view to overthrowing Diem, establishing a coalition government, and setting Vietnam back on the road to reunification.

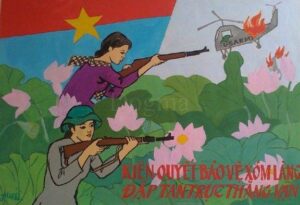

The NLF, along with the People’s Liberation Army it established a few months later, quickly took root among the masses of the people, establishing liberated territory across much of the countryside. Diem’s programme of repression became increasingly ineffective against this tried-and-tested resistance movement (largely led by veterans of the war against the French, and supplied by Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) forces). Realising the hopelessness of his government’s situation, Diem secretly established contact with the NLF and the DRV government with a view to negotiating a peaceful solution. This proved to be his undoing. His US backers, totally unsympathetic to the idea of negotiating away their dream of permanent domination of the region, had him overthrown and killed. “The deeply shaken Saigon regime and army were plunged into an endless crisis: within 20 months since the fall of Diem, thirteen coups, nine cabinets and four charters followed one after another.” (Ngo Vinh Long)

Meanwhile, the US military escalation in the early 1960s had not had the desired effect. ”There were 800 American military personnel in South Vietnam when Kennedy took office [January 1961] and 16,700 when he died in November 1963. The National Liberation Front controlled the majority of villages in the South when Kennedy took office; they continued to do so in the year of his death, and basic American policy was also unchanged” (Young). With the NLF controlling at least 75% of the country, the US understood that it was only a matter of time before the South Vietnam government and army were defeated outright. In that context the US would have been well advised to accept the situation and to negotiate for a united Vietnam that was neutralist and not overtly hostile to the US – the NLF and DRV regularly stated their willingness to negotiate on such a basis (in the famous words of Ho Chi Minh, “If the Americans want to make war for twenty years then we shall make war for twenty years. If they want to make peace, we shall make peace and invite them to afternoon tea.”). Sadly, President Johnson and his advisors chose the other option: death and destruction on an unprecedented scale.

On 2 March 1965, ‘Operation Rolling Thunder’ – the bombing of the north – began. A week later, the first few thousand US ground troops landed in the south.

Unparalleled destruction

The US war against Vietnam was, and remains, “the most atrocious colonial war in human history” – a case of brutal, uneven violence of holocaust proportions. Nick Turse, in his meticulously-researched book ‘Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam’, describes vividly the obscene ‘technowar’ perpetrated by the US:

They shook the earth with howitzers and mortars. In a country of pedestrians and bicycles, they rolled over the landscape in heavy tanks, light tanks, and flame-thrower tanks. They had armoured personnel carriers for the roads and fields, swift boats for rivers, and battleships and aircraft carriers off shore. The Americans unleashed millions of gallons of chemical defoliants, millions of pounds of chemical gases, and endless canisters of napalm; cluster bombs, high-explosive shells, and daisy-cutter bombs that obliterated everything within a ten-football-field diameter; antipersonnel rockets, high-explosive rockets, incendiary rockets, grenades by the millions, and myriad different kinds of mines. Their advanced weapons included M-16 rifles, M-60 machine guns, M-79 grenade launchers, and even futuristic technologies that would only later enter widespread use, like electronic sensors and unmanned drones. In other words, in Vietnam the American military amassed an arsenal unlike any seen before. As it faced off against guerrillas armed with old rifles and homemade grenades fashioned out of soda cans—or North Vietnamese troops with AK-47 assault rifles and rocket-propelled grenade launchers—the United States had at its disposal more killing power, destructive force, and advanced technology than any military in the history of the world.

Reliable academic studies put the total death toll at just under 4 million people, the overwhelming majority of them Vietnamese peasants. The total munitions unleashed by the US in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia “added up to the equivalent of 640 Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs” (ibid). Highly toxic defoliants such as Agent Orange were sprayed far and wide, directly affecting up to 5 million Vietnamese. “Immediate reactions to exposure included nausea, cramps, and diarrhoea. In the longer term, the defoliants have been associated with higher incidence of stillbirths as well as a variety of illnesses, including cancers and birth defects such as anencephaly and spina bifida. Children born decades after the war still suffer the aftereffects.”

US military scientists, keen to build on their chemical weapons innovations from the Korean War, developed new variants of napalm and white phosphorus. “An estimated 400,000 tons of it were dropped in Southeast Asia, killing most of those unfortunate enough to be splashed with it.”

Thanks to the landmark reporting by Seymour Hersh and the bravery of the whistleblower, Ron Ridenhour, the March 1968 massacre at My Lai crept into the international media and became one of the defining moments of the war. Nick Turse describes the unmitigated horror unleashed on the people of My Lai by Charlie Company of the 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment: “The Americans entering My Lai encountered only civilians: women, children, and old men. Many were still cooking their breakfast rice… Soldiers of Charlie Company killed. They killed everything. They killed everything that moved. Advancing in small squads, the men of the unit shot chickens as they scurried about, pigs as they bolted, and cows and water buffalo lowing among the thatch-roofed houses. They gunned down old men sitting in their homes and children as they ran for cover. They tossed grenades into homes without even bothering to look inside. An officer grabbed a woman by the hair and shot her point-blank with a pistol. A woman who came out of her home with a baby in her arms was shot down on the spot. As the tiny child hit the ground, another GI opened up on the infant with his M-16 automatic rifle. Over four hours, members of Charlie Company methodically slaughtered more than five hundred unarmed victims, killing some in ones and twos, others in small groups, and collecting many more in a drainage ditch that would become an infamous killing ground. They faced no opposition. They even took a quiet break to eat lunch in the midst of the carnage. Along the way, they also raped women and young girls, mutilated the dead, systematically burned homes, and fouled the area’s drinking water.” (ibid)

Perhaps the most shocking thing about the My Lai massacre is that it was by no means out of the ordinary. The only really unusual thing about it was that it made the news in the west. In truth, numerous massacres on a similar scale took place. “Murder, torture, rape, abuse, forced displacement, home burnings, specious arrests, imprisonment without due process—such occurrences were virtually a daily fact of life throughout the years of the American presence in Vietnam… They were no aberration. Rather, they were the inevitable outcome of deliberate policies, dictated at the highest levels of the military.”

Turse notes that US soldiers in Vietnam were brainwashed with an intense racist hatred of the Vietnamese people. He cites an army veteran, Wayne Smith: “The drill instructors never ever called the Vietnamese, ‘Vietnamese.’ They called them dinks, gooks, slopes, slants, rice-eaters, everything that would take away humanity … That they were less than human was clearly the message.” The message of Vietnamese inferiority came right from the top: “To President Johnson, Vietnam was ‘a piddling piss-ant little country.’ To McNamara, a ‘backward nation.’ President Nixon’s national security adviser Henry Kissinger called North Vietnam a ‘little fourth-rate power,’ later downgrading it to ‘fifth-rate’ status. Such feelings permeated the chain of command, and they found even more colourful voice among those in the field, who regarded Vietnam as ‘the outhouse of Asia,’ ‘the garbage dump of civilisation,’ ‘the asshole of the world.’” (ibid)

While the people of the south were being subjected to the systematic terror of the US ground war, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was victim to the most intense bombing campaign in history. International law was flouted again and again, as the US air forces bombed water supplies, fuel depots, bridges and transportation systems, essentially in a bid to starve North Vietnam into submission. Turse notes that, “on average, between 1965 and 1968, thirty-two tons of bombs per hour were dropped on the North.”

When President Johnson was forced to call an end to the bombardment of the north in 1968, he simply diverted his B-52s to Laos in order to attack the Pathet Lao resistance movement and to bomb the Ho Chi Minh Trail – the covert supply route from north to south Vietnam, much of which ran through Laos. In the Plain of Jars region in northeastern Laos, “nothing was left standing… In the last phase, bombings were aimed at the systematic destruction of the material basis of civilian society” (George Chapelier, UN advisor in Laos, cited in Young). Similarly, Cambodia was carpet-bombed from 1969 to 1973, resulting in an estimated 150,000 deaths and a refugee crisis affecting two million people (over quarter of the population). The Ho Chi Minh Trail, meanwhile, stayed open. According to the US National Security Agency’s official history of the war, it was “one of the great achievements of military engineering of the 20th century.”

The stark inhumanity and painful futility of the US war is brilliantly captured by poet Bryan Alec Floyd:

This is what the war ended up being about:

We would find a V.C. village,

and if we could not capture it

or clear it of Cong,

we called for jets.

The jets would come in, low and terrible,

sweeping down, and screaming,

in the first pass over the village.

Then they would return, dropping their first bombs

that flattened the huts to rubble and debris.

And then the jets would sweep back again

and drop more bombs

that blew the rubble and debris

to dust and ashes.

And then the jets would come back once again,

in a last pass, this time to drop napalm

that burned the dust and ashes to just nothing.

Then the village

that was not a village any more

was our village.

Victory to Vietnam

“B-52s and computers can’t compete with a just cause and human intelligence” – Pham Van Dong (Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, 1970).

“Be loyal to the country and devoted to the people, fulfil all tasks, overcome all difficulties, defeat all enemies.” – Ho Chi Minh

For all the sophisticated military technology and the obscene brutality; in spite of the billions of dollars spent, the millions of lives destroyed, the endless strategic shifts and the best efforts of numerous US presidents (Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, Nixon, Ford); the US simply could not win in Vietnam. From north to south, the ordinary Vietnamese people refused to be defeated. As Ho Chi Minh correctly predicted: “We, a small nation, will have earned the signal honour of defeating, through heroic struggle, two big imperialisms – the French and the American – and of making a worthy contribution to the world national liberation movement.”

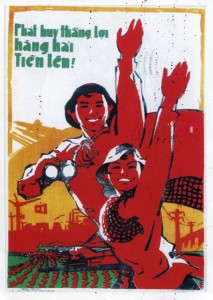

The US escalation reached its highest point in 1968, at which point there were over half a million US troops, along with over a million mercenary troops from the South Vietnamese puppet army, and a few thousand from South Korea, Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Thailand and Taiwan. Totally confident that victory was just around the corner, and failing to understand the extent of popular support for the NLF, the US refused to negotiate with the NLF or DRV at any point during the first three years of full-scale war. Yet the US and Saigon forces couldn’t make any headway in defeating their enemy. In early 1967, a US Senate Armed Forces Committee report stated that “the Viet Cong [pejorative name for the NLF] still control 80 percent of South Vietnam territory” (cited in Ngo Vinh Long). Attacked ferociously with napalm and helicopter gunships, and sustaining tens of thousands of casualties, the NLF nevertheless continued to grow in number and influence, using guerrilla warfare “not to wage large-scale battles and win big victories, but to nibble at the enemy, harass him in such a way that he can neither eat nor sleep in peace, to give him no respite, to wear him out physically and mentally, and finally to annihilate him.” (Ho Chi Minh)

Naomi Cohen writes: “The NLF was fighting a people’s war… Having won the vast majority of the people over to the resistance, the NLF was in fact indistinguishable from the people. Thus the US and its puppet regime in Saigon engaged in one tactic after another to isolate the NLF from the general population. When it became clear that the rural population was feeding and sheltering the resistance fighters, the US tried to herd the people into ‘strategic hamlets’, which were nothing but concentration camps, to try to cut off support to the NLF fighters. The Pentagon used chemical warfare, dropping Agent Orange to defoliate jungle hideouts and destroy crops. When these tactics didn’t work, relentless bombing of so-called ‘free-fire zones’ followed.”

None of the US’ strategies worked. Since the US would not voluntarily sit down and negotiate, the Vietnamese revolutionaries had to force the issue. They did so with dazzling effectiveness. The Tet Offensive, widely considered to be the major turning point of the war, was launched during the Tet (Lunar New Year) celebrations in January 1968. This coordinated attack by NLF forces took place in 140 cities and towns simultaneously, to the complete shock and surprise of the US and its quislings in South Vietnam.

“The NLF forces, without any modern means of transportation or communications attacked almost every major military and administrative installation in South Vietnam in complete secrecy under the noses of the most sophisticated military machine that has ever taken the field… Among the objectives attacked were all four zonal headquarters of the Saigon Army, eight out of 11 divisional headquarters, and two American army field headquarters. Among the 18 major targets attacked in Saigon itself were the US embassy, the ‘Presidential Palace,’ the joint US-Saigon armed forces headquarters, and the South Vietnam naval headquarters.” (Wilfred Burchett, ‘Vietnam Will Win’)

The Tet Offensive proved to the world that the Vietnamese could not be defeated; that the US would have no choice but to negotiate; that all the saturation bombing and state terrorism were only strengthening the resolve of the NLF and DRV. It caused a major re-think in Washington and led to Lyndon Johnson’s refusal to stand for a second term as president (in itself a clear admission that the Vietnam War was unwinnable). It also inspired Richard Nixon’s policy of ‘Vietnamization’: getting the South Vietnamese puppet army to fight the ground war, with the US gradually withdrawing its ground troops and focusing on the genocidal aerial bombing of Cambodia, Laos and North Vietnam.

Tet also had a big impact on the willingness of ordinary US soldiers to fight the war, and on the anti-war movement in the US itself, which grew to become an important source of pressure on the government.

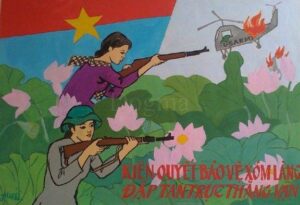

Meanwhile, the US air war against the north was going far from smoothly. In the course of the war, the US lost approximately 10,000 aircraft and helicopters to surface-to-air missiles, anti-aircraft artillery and Soviet MiG fighter planes. Thousands of small air raid shelters were built across the north in order to protect the population. Vietnamese doctor Ton That Tung put it bluntly: “The Americans thought that the more bombs they dropped, the quicker we would fall to our knees and surrender. But the bombs heightened rather than dampened our spirit.”

Meanwhile, the US air war against the north was going far from smoothly. In the course of the war, the US lost approximately 10,000 aircraft and helicopters to surface-to-air missiles, anti-aircraft artillery and Soviet MiG fighter planes. Thousands of small air raid shelters were built across the north in order to protect the population. Vietnamese doctor Ton That Tung put it bluntly: “The Americans thought that the more bombs they dropped, the quicker we would fall to our knees and surrender. But the bombs heightened rather than dampened our spirit.”

With an army in crisis (AWOLs and desertion were rampant, morale was the lowest it had ever been, and drug addiction was becoming an epidemic among GIs), an increasingly effective anti-war movement at home, and no prospect of wiping out Vietnamese resistance in South Vietnam, Nixon turned his attention to Cambodia, where the Central Office for South Vietnam (COSVN, the DRV’s political headquarters in charge of running its war effort) was rumoured to be located. “In May 1970, over 50,000 US and Saigon troops invaded Cambodia to ‘clean up the sanctuaries’ and dismantle the ‘Vietcong Pentagon’. This invasion was preceded by the most massive air bombardments since the start of the Vietnam war, including for the first time B-52 bomber raids against towns, wiping out half a dozen frontier towns in as many minutes.” (Ngo Vinh Long)

One unintended effect of the Cambodia invasion is the breathing space it gave to the NLF inside South Vietnam, which by the end of 1971 had fully recovered from the post-Tet counter-offensive.

On 30 March 1972, the DRV People’s Army tanks “rolled across the demilitarised zone in the first of a three-pronged offensive whose force and power should have been, but were not, expected… In the mountains where the Laos, Cambodian, and Vietnamese borders meet, American advisers on advanced fire bases could hear the bulldozers of the North Vietnamese engineer corps widening old roads and building new ones. Using tanks and heavy artillery, a combined force totalling 200,000 North Vietnamese and NLF troops swept aside ARVN defences, challenging the premise as well as the substance of Vietnamization. For Hanoi, this was the main point of the entire effort: to demonstrate to Nixon that Vietnamization would not work, that his administration would have to sit down to serious negotiations or look forward to an endless war in Vietnam.” (Young)

On 30 March 1972, the DRV People’s Army tanks “rolled across the demilitarised zone in the first of a three-pronged offensive whose force and power should have been, but were not, expected… In the mountains where the Laos, Cambodian, and Vietnamese borders meet, American advisers on advanced fire bases could hear the bulldozers of the North Vietnamese engineer corps widening old roads and building new ones. Using tanks and heavy artillery, a combined force totalling 200,000 North Vietnamese and NLF troops swept aside ARVN defences, challenging the premise as well as the substance of Vietnamization. For Hanoi, this was the main point of the entire effort: to demonstrate to Nixon that Vietnamization would not work, that his administration would have to sit down to serious negotiations or look forward to an endless war in Vietnam.” (Young)

The US leadership could see the writing on the wall. On 17 January 1973, the Paris Peace Agreements were signed. The accords called for an immediate ceasefire, the full withdrawal of US troops, and negotiations between Saigon and the NLF towards inclusive elections and reunification. That is to say: the US went to Indochina, killed millions of people, devastated the environment and infrastructure, and agreed to a peace deal on pretty much the same terms as it had rejected 19 years earlier (the Geneva Accords).

The last American ground troops left Vietnam on March 29, 1973. With the US forces largely out of the picture, it was a foregone conclusion that the puppet government in Saigon would collapse soon enough. Two hundred thousand men deserted the South Vietnamese army in 1974 alone.

At the end of 1974, the DRV generals made the decision to push for final victory, with the hope of liberating Saigon in 1976 or 1977. In fact, victory came far quicker as the South Vietnamese forces, demoralised and disintegrating, gave very little resistance. Sweeping down from the north, the joint forces of the North Vietnamese People’s Army and the National Liberation Front quickly liberated Hue and Da Nang. Much of the central strip was liberated without a fight.

With the revolutionary army approaching Saigon, US Ambassador Martin asked the South Vietnamese president, Thieu, to resign, in the hope that the NLF would be willing to reach an accommodation with his successor, Duong Van Minh, who had a reputation for being more favourable to a peaceful resolution to the conflict. However, Saigon was already encircled. “On the morning of April 30, Minh ordered a general cease-fire. ‘In a final extraordinary irony,’ James Harrison writes, ‘the man who transmitted Minh’s cease-fire order, a one-star general named Nguyen Huu Hanh, was a longtime Communist agent.’” (Young)

The revolutionary forces had won control of the entire country. It was a profoundly significant and emotional moment, one that should be remembered and treasured by all who long for freedom and who oppose imperialism.

“At the front headquarters, we turned on our radios to listen. The voice of the quisling president called on his troops to put down their weapons and surrender unconditionally to our troops. Saigon was completely liberated! Total victory! We were completely victorious! All of us at headquarters jumped up and shouted, embraced and carried each other around on our shoulders. The sound of applause, laughter, and happy, noisy, chattering speech was as festive as if spring had just burst upon us. It was an indescribably joyous scene. Le Duc Tho and Pham Hung embraced me and all the cadres and fighters present. We were all so happy we were choked with emotion… This historic and sacred, intoxicating and completely satisfying moment was one that comes once in a generation, once in many generations. Our generation had known many victorious mornings, but there had been no morning so fresh and beautiful, so radiant, so clear and cool, so sweet-scented as this morning of total victory, a morning which made babes older than their years and made old men young again.” (Van Tien Dung, ‘Our Great Spring Victory’)

A legacy that will never lose its relevance

History is meaningless if it’s just a bunch of interesting stories from the past. History is rendered meaningful through the lessons it offers, the tools it gives us to help solve the problems we have today. The people of Vietnam – a relatively small, underdeveloped, oppressed country – were able to comprehensively defeat French and then US imperialism. Given that imperialism still exists in the world; given that the number one task for the liberation (and indeed survival) of humanity is to end imperialism at a global level; it’s clear that we need to understand how the Vietnamese achieved what they did.

The role of ideology

As discussed above in relation to the birth of the Indochinese Communist Party and the Viet Minh, Marxist-Leninist ideology played a decisive role in defining the tasks of the Vietnamese Revolution (which can be considered to have started in the 1920s and which is ongoing) and creating a lasting alliance of workers, peasants and intellectuals. Truong Chinh, in his pamphlet ‘Forward Along the Path Charted by Karl Marx’, writes: “During nearly a century under French colonialist rule, finding life impossible under the oppressive regime of the colonialists and the feudalists, our people had risen up to struggle courageously for the independence and freedom of the fatherland. For one who fell, others rushed forward. But all national-liberation movements before the birth of our party had failed. One of the causes for this failure lies in the inability of those revolutionaries to develop the scientific world outlook of the working class, the most revolutionary class of our time, hence to work out an adequate programme capable of leading the Vietnamese revolution to victory.”

Marxism for the first time places the masses at the centre stage in history. The oppressed, the exploited, the sufferers, the people who slave and toil, for the first time become the active element, the force driving society forward. Le Duan, leader of reunified Vietnam until his death in 1986, writes: “It was not until the birth of Marxism that the masses were recognised as makers of history… Workers, peasants, urban and rural toilers, and revolutionary intellectuals, all belong to the family of the toiling masses. Only by paying attention to their aspirations and interests, can we rouse their determination and enthusiasm, and develop their inexhaustible creativeness to overcome all difficulties and speed up the revolution.”

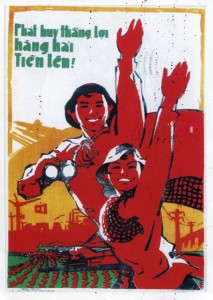

Combined with Leninism, which extends Marxism from its European birthplace and applies it to the conditions of an imperialist-dominated world, this ideology enabled Ho Chi Minh and his comrades to define the social classes that could be brought into the struggle; to build a vast revolutionary mass movement capable of fighting and winning; to make revolutionary science comprehensible to ordinary workers and peasants; and to develop the level of unity needed to defeat the strongest enemies (“Without this unity we would be like an orchestra in which the drums play one way and the horns another; it would not be possible for us to lead the masses and make revolution” – Ho Chi Minh). Furthermore scientific socialism, with its emphasis on equality and social progress, helped the Vietnamese resistance to draw women into political activity on an equal basis with men. The unprecedented role of female guerrilla fighters in the Vietnam wars attests to this.

It was the communists who had the understanding, the strategy and the vision that was needed to bring about liberation – as was the case in China. Naomi Cohen puts it simply: “The Vietnamese people, who began their war of liberation with only bows and arrows, were organised by communist revolutionaries into the most determined and experienced anti-imperialist fighting force ever seen. This is how they defeated the most powerful military on earth.”

Global solidarity

On the frontline of the global struggle against imperialism, Vietnam had the support of progressive people worldwide. The support of the socialist camp was certainly a crucial factor in the continued successes of the Vietnamese Revolution.

Red China provided a rear base, along with hundreds of thousands of troops, large quantities of weapons and other supplies, and valuable military experience gained in the struggle for national liberation (not to mention the experience of the millions of People’s Volunteers who fought alongside North Korea between 1950 and 1953).

The Soviet Union provided decisive support in the form of advanced weaponry, including surface-to-air missiles and fighter jets, as well as medical supplies, tanks, helicopters, and several thousand troops. Soviet military schools and academies also provided training for thousands of Vietnamese soldiers.

A North Korean air force regiment helped to defend North Vietnam against air attacks (providing a counterpart to the thousands of South Korean ground troops sent to fight in Vietnam on the side of the US by the stooge dictatorship of Park Chung-hee). Kim Il-sung encouraged the North Korean pilots to “fight in the war as if the Vietnamese sky were their own.” Even Cuba, thousands of miles away, sent military advisers.

As Ho Chi Minh put it: “All achievements of our Party and people are inseparable from the fraternal support of the Soviet Union, People’s China and the other socialist countries, the international communist and workers’ movement and the national-liberation movement and the peace movement in the world. If we have been able to surmount all difficulties and lead our working class and people to the present glorious victories this is because the Party has coordinated the revolutionary movement in our country with the revolutionary movement of the world working class and the oppressed peoples.”

With his obsessive focus on unity, Ho Chi Minh was able to skilfully navigate the Sino-Soviet split (which he correctly regarded as a disaster), maintaining close relations with both sides right up to his death in 1969. (It is telling that one of the key paragraphs in his testament addresses the split: “Being a man who has devoted his whole life to the revolution, the more proud I am of the growth of the international communist and workers’ movement, the more pained I am by the current discord among the fraternal Parties. I hope that our Party will do its best to contribute effectively to the restoration of unity among the fraternal Parties on the basis of Marxism-Leninism and proletarian internationalism, in a way which conforms to both reason and sentiment. I am firmly confident that the fraternal Parties and countries will have to unite again.”)

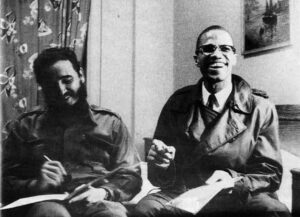

The anti-war movement in the US also had an important impact. Although the role of this movement is sometimes overstated by those who want to negate the role of the Vietnamese masses in freeing themselves, there’s no question that this movement struggled bravely and creatively, and as a result was able to pull a large portion of the US public towards an anti-war position. This in turn served to somewhat restrain the US government, and may well have influenced the decisions to withdraw troops and to end congressional funding to the South Vietnamese army. The role of civil rights and black liberation movement leaders in the anti-war movement made a historically important link between the struggle against imperialism abroad and the struggle against imperialism and racism at home; a link that needs to be emphasised today, when the same imperialist ruling classes are fuelling civil war in Syria, seeking the overthrow of the government in Venezuela, and killing unarmed black people on the streets of Baltimore, New York and Ferguson.

The anti-war movement in the US also had an important impact. Although the role of this movement is sometimes overstated by those who want to negate the role of the Vietnamese masses in freeing themselves, there’s no question that this movement struggled bravely and creatively, and as a result was able to pull a large portion of the US public towards an anti-war position. This in turn served to somewhat restrain the US government, and may well have influenced the decisions to withdraw troops and to end congressional funding to the South Vietnamese army. The role of civil rights and black liberation movement leaders in the anti-war movement made a historically important link between the struggle against imperialism abroad and the struggle against imperialism and racism at home; a link that needs to be emphasised today, when the same imperialist ruling classes are fuelling civil war in Syria, seeking the overthrow of the government in Venezuela, and killing unarmed black people on the streets of Baltimore, New York and Ferguson.

In many ways, Vietnam was a victory not just for the revolutionary forces of Vietnam but for the progressive forces of the world, and a lesson as to what we can accomplish if we’re united.

Building socialism and solidarity, against all odds

Our rivers, our mountains, our people will always be; The American aggressors defeated, we will build a country ten times more beautiful.

With invaders and puppet armies finally defeated, the Vietnamese Revolution moved immediately on to a new phase: reunifying the country, rebuilding it, coming to terms with the extent of the destruction, dealing with the abundance of social, economic and political problems that the war left behind, and trying to move forward to socialism. Van Tien Dung writes movingly of his thoughts in the hours and days following victory: “We thought of the welter of jobs ahead. Were the electricity and water in Saigon still working? Saigon’s army of nearly 1 million had disbanded on the spot. How should we deal with them? What could we do to help the hungry and find ways for the millions of unemployed to make a living? Should we ask the centre to send in supplies right away to keep the factories in Saigon alive? How could we quickly build up a revolutionary administration at the grassroots level? What policy should we take toward the bourgeoisie? And how could we carry the South on to socialism along with the whole country? The conclusion of this struggle was the opening of another, no less complex and filled with hardship. The difficulties would be many, but the advantages were not few. Saigon and the South, which had gone out first and returned last, deserved a life of peace, plenty and happiness.”

The Vietnamese leadership had hundreds of very real problems to deal with; new problems needing creative solutions. In the south, the new government inherited, according to its own estimates, “twenty million bomb craters, ten million refugees, 362,000 war invalids, one million widows, 880,000 orphans, 250,000 drug addicts, 300,000 prostitutes and three million unemployed; two-thirds of the villages were destroyed.”

The population of Saigon had multiplied during the course of the war, with millions seeking refuge from the war in the countryside; by 1975, it was far and away the most densely populated city in the world. The war had caused immense environmental destruction throughout the country, creating significant health and economic problems. Much of the industrial infrastructure of the north had been damaged and needed rebuilding.

If there was ever a country in need of development aid, it was Vietnam. And yet very little was forthcoming. Everybody’s favourite ‘liberal’ US president, Jimmy Carter, refused to normalise relations with Vietnam or to provide any aid whatsoever, stating that “the destruction was mutual”. (As Chomsky said, “if words have meaning, this must stand among the most astonishing statements in diplomatic history”). Meanwhile, the growing hostility between Vietnam and China (related to the Sino-Soviet split and to the ongoing war in Cambodia) led to China cutting off aid to Vietnam in the late 70s. Vietnam was left very much dependent on a Soviet Union that, by the mid-80s, was in a state of terminal decline.

Those who walk the road know it is hard.

Scale one mountain and another appears.

But once you mount the highest peak,

10,000 miles appear before your eyes.

(Ho Chi Minh, prison diary)

In spite of everything, the Vietnamese people and government have re-built their country; have constructed a modern, viable, strong, independent, socialist state. It has been, and remains, a complex and difficult path to a brighter future, with many unexpected twists and turns, but one thing we can say for certain is that the Vietnamese people are in a position thousands of times better than what they endured under French and US colonialism.

When the Soviet Union and the eastern European people’s democracies fell in the late 80s and early 90s, economic hard times quickly fell on Vietnam. It had to change tactics, but it didn’t change its road. Along with Cuba, China, North Korea and Laos, Vietnam forms part of a small group of heroic countries that “did not abandon the principles of Marxism-Leninism, or of popular democratic government, or of the leadership of the Communist Party” and that are “persisting in socialism – in spite of the enormous difficulties resulting from us being left almost alone – using our intelligence, using our hearts, using our creative spirit, … capable of introducing innovations which will not only save socialism, but will improve it, and one day will bring it to a definitive triumph.” (Fidel Castro speech in Ho Chi Minh City, 1996)

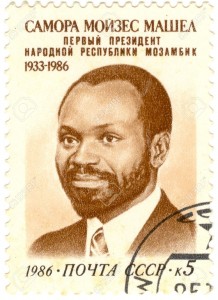

The unity, bravery, heroism, creativity, discipline, endurance and selflessness of the Vietnamese people is a profound lesson to all those struggling for freedom, independence and socialism. In the 60s, 70s and 80s, Vietnam gave great inspiration to the masses of Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Angola, Namibia, Guinea Bissau and South Africa. Today, it is our duty to study and understand how the history of the Vietnamese freedom struggle informs our modern-day anti-imperialist struggle, be it in Ukraine, Syria, Libya, Congo, Yemen, or in the streets of London, Paris and Baltimore.

The unity, bravery, heroism, creativity, discipline, endurance and selflessness of the Vietnamese people is a profound lesson to all those struggling for freedom, independence and socialism. In the 60s, 70s and 80s, Vietnam gave great inspiration to the masses of Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Angola, Namibia, Guinea Bissau and South Africa. Today, it is our duty to study and understand how the history of the Vietnamese freedom struggle informs our modern-day anti-imperialist struggle, be it in Ukraine, Syria, Libya, Congo, Yemen, or in the streets of London, Paris and Baltimore.

Suggested further reading

- Ho Chi Minh – Selected Works

- Marilyn Young – The Vietnam Wars 1945-1990

- Nick Turse – Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam

- Ngo Vinh Long – Coming to Terms: Indochina, the United States, and the War

- Van Tien Dung – Our Great Spring Victory

- William Duiker – Ho Chi Minh: A Life

- Nguyen Thi Dinh – No Other Road to Take

- Vo Nguyen Giap – Selected Works

- Truong Chinh – Forward Along the Path Charted by Karl Marx