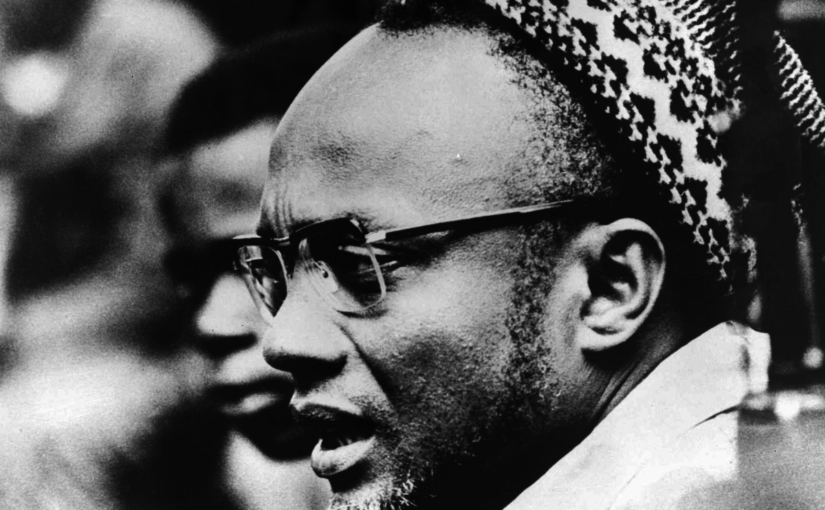

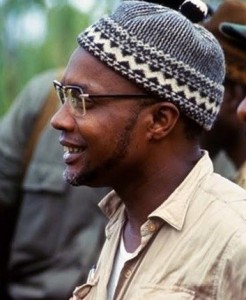

Amílcar Lopes da Costa Cabral, one of the greatest anti-colonial leaders of the twentieth century, was born on the 12th of September 1924 in Bafatá, a small town in central Guinea-Bissau. Today, ninety years later, let us take a moment to remember this brilliant revolutionary – the undisputed leader and architect of the struggle to liberate Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde from the yoke of Portuguese colonialism.

As a revolutionary theorist, as a guerrilla fighter, as an inspiring agitator, as an uncompromising internationalist, Cabral’s legacy continues to inform the global struggle against imperialism and for socialism.

From a base of almost nothing, he was able to lead the construction of the most successful guerrilla movement in Africa and a strong, disciplined political party: the Partido Africano da Independência da Guiné e Cabo Verde (PAIGC). Fidel Castro referred to him as “one of the most lucid and brilliant leaders in Africa, who instilled in us tremendous confidence in the future and the success of his struggle for liberation.”

Cabral built close links with the liberated African countries (in particular Guinea, Ghana, Tanzania, Algeria and Libya) as well as the liberation movements fighting colonialism in Mozambique, South Africa and Angola. Furthermore, he located the PAIGC’s struggle against colonialism within the global struggle against imperialism and for socialism, and on this basis forged close ties with the entire socialist camp, including the Soviet Union, China, the German Democratic Republic, Cuba and Vietnam. (The PAIGC was one of the few movements in the 60s and 70s to successfully navigate the Sino-Soviet split and maintain close relations with both the Soviet Union and China).

Cabral was surely a man of action, but he was also an important and innovative political thinker who made an outstanding contribution to anti-imperialist, socialist, pan-Africanist and revolutionary nationalist ideologies. Tetteh Kofi writes that Cabral “charted a new ideological path, extending the works of Marx and Lenin to suit African realities. Cabral was the leading political theorist of the Lusophone leaders, until his assassination in 1973” (cited in Reiland Rabaka ‘Concepts of Cabralism: Amilcar Cabral and Africana Critical Theory’).

Portugal’s racist policy – along with its own backwardness – meant that very few people in its colonies had access to higher education. In Guinea Bissau at the time, there was only a handful of university graduates in the whole country. However, Cabral displayed exceptional academic ability, and this enabled him to study at the University of Lisbon, where he met people like Agostinho Neto and Eduardo Mondlane (who would go on to lead the revolutionary movements in Angola and Mozambique respectively). In Portugal, his fellow African students introduced him to socialist ideology, and they spent much of their time studying, discussing and strategising: how to end colonial domination of their homelands? How to inspire the broad masses of the people to engage in struggle?

Cabral returned to Guinea Bissau in 1951 and worked for some years as an agronomist – which experience “provided him with ample opportunity to learn at first hand of the dire poverty and intense suffering of his people, especially in the countryside. His experiences made him more determined than ever to find ways and means of working for the freedom of his country and delivering his people from the yoke of colonial bondage.”

Living for a brief spell in Angola, he was a founder member of Angola’s preeminent liberation organisation, Movimento Popular Libertação de Angola (MPLA), along with his university friend Agostinho Neto. In the same year (1956), he and his comrades founded the African Party of Independence of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde Islands (PAIGC).

ANC and SACP stalwart Yusuf Dadoo writes: “Under his leadership the PAIGC mobilised the country’s patriots to struggle for the freedom of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde Islands, created the people’s army and led the national-liberation war against the Portuguese colonialists. Cabral knew and understood his enemy well, and every phase of the struggle was carefully planned and action meticulously organised. The cadres of the PAIGC were given political education as well as military training and he stressed always ‘that we are armed militants and not militarists.’”

In 1963, after several years of careful planning, study and strategising, the PAIGC launched its military campaign, which over the course of a few years was able to win the support and loyalty of the Guinean and Capeverdian masses and which managed to shake the rotting colonial entity to its foundations. The first liberated zones were set up in 1965, and these continued to expand unstoppably until independence in 1974, by which time practically the entire country was in the hands of the revolutionary forces.

Sadly, Cabral did not live to see the final victory of the national liberation struggle, and Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde were deprived of the insightful leadership that he would doubtless have provided in the post-colonial period. On 20 January 1973, he was kidnapped and shot by disgruntled PAIGC members working in collaboration with the Portuguese secret police.

Nonetheless, the heroic people of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde stepped up their fight, with Amílcar Cabral’s name on their lips.

Piero Gleijeses notes that, “a few weeks after Cabral’s death, the PAIGC was decisively strengthened by the delivery of surface-to-air missiles from the Soviet Union. Until then, the rebels had not had an effective defense against Portuguese air power, but in late 1972, Luis Cabral recounts, ‘we learned about a Soviet anti-aircraft weapon that was light and very efficient. Amilcar made a special trip to Moscow to explain our needs to the Soviet authorities and to urge them to give us that precious weapon.’ The mission, in December 1972, proved successful. In March 1973 the Portuguese prime minister wrote, ‘surface-to-air missiles unexpectedly appeared in the enemy’s hands in Guinea-Bissau and within a few days five of our planes had been shot down.’ This meant that ‘our unchallenged air superiority, which had been our trump card and the basis of our entire military policy … had suddenly evaporated.’” (Conflicting Missions)

By mid-1973, the PAIGC had extended its liberated territory to cover more than two-thirds of the country. On 24 September 1973, the Popular National Assembly proclaimed the independent state of Guinea-Bissau. Full independence was finally granted a year later, on 10 September 1974. Portugal had, in the course of 11 years’ severe warfare, been well and truly defeated.

Meanwhile, the revolutionary anti-colonial wars had played a major part in bringing about the economic and political crisis within Portugal itself, and had been an inspiration for the most progressive elements within the Portuguese left. The overthrow of fascism in Portugal owes much to the heroic struggle waged by the people of Guinea Bissau, Cape Verde, Angola and Mozambique.

Patrick Chabal, in ‘Revolutionary Leadership and People’s War’, sums up Cabral’s legacy succinctly:

In less than twenty years of active political life, Cabral led Guinea-Bissau’s nationalists to the most complete political and military success ever achieved by an African political movement against a colonial power. At the time of his death in 1973, months before Guinea-Bissau became independent, his influence extended well beyond the Lusophone world and Africa. Friends and foes alike admired his political acumen and skills and saw in him a potential leader of the non-aligned movement. His writings have shown him to be a sophisticated analyst of the social, economic and political factors which have affected and continue to affect the developing world.

We publish below a selection of valuable quotes by (and a few about) Amílcar Cabral, which are meant to serve as an introduction to his ideological legacy. The quotes are followed by some suggestions for further reading.

Theory and practice

As someone born in a country where a foreign colonial power pointedly refused to allow the vast majority of the population access to learning, Cabral had little time for anti-intellectual strands within the progressive movement. Indeed he strongly felt that the existing anti-imperialist movements were much in need of greater ideological grounding.

The ideological deficiency within the national liberation movements, not to say the total lack of ideology – reflecting as this does an ignorance of the historical reality which these movements claim to transform – makes for one of the greatest weaknesses in our struggle against imperialism, if not the greatest weakness of all. (source)

On the connection between theory and practice, he strikes a similar chord to Mao:

Every practice produces a theory, and though it is true that a revolution can fail even though it be based on perfectly conceived theories, nobody has yet made a successful revolution without a revolutionary theory. (ibid)

Very early on in their struggle, and with hardly any resources at their disposal, the PAIGC founders set up a political school in order to create cadres.

The fact that the Republic of Guinea was next to us enabled our Party to install there, temporarily, some of our leaders, and this enabled us to create a political school to prepare political activists. This was decisive for our struggle. In 1960 we created a political school in Conakry, under very poor conditions. Militants from the towns – party members – were the first to come to receive political instruction and to be trained in how to mobilise our people for the struggle. After comrades from the city came peasants and youths (some even bringing their entire families) who had been mobilised by Party members. Ten, twenty, twenty-five people would come for a period of one or two months. During that period they went through an intensive education programme; we spoke to them, and night would come and we couldn’t speak any more because we were completely hoarse. (source)

In his celebrated directive ‘Tell no lies, claim no easy victories’, he urges:

Educate ourselves, educate other people, the population in general, to fight fear and ignorance, to eliminate little by little the subjugation to nature and natural forces which our economy has not yet mastered. Convince little by little, in particular the militants of the Party, that we shall end by conquering the fear of nature, and that man is the strongest force in nature. Demand from responsible Party members that they dedicate themselves seriously to study, that they interest themselves in the things and problems of our daily life and struggle in their fundamental and essential aspect, and not simply in their appearance. Learn from life, learn from our people, learn from books, learn from the experience of others. Never stop learning. (source)

Socialism

Cabral’s major focus as a revolutionary was to create maximum national unity against Portuguese colonialism, and therefore much of his thought is framed in terms of revolutionary nationalism rather than specifically socialism. Nonetheless, he was very clear about what he thought post-colonial Africa should look like. Furthermore, he established very close links with the existing socialist camp, including the Soviet Union, Cuba, the German Democratic Republic, China and Cuba.

In our present historical situation — elimination of imperialism which uses every means to perpetuate its domination over our peoples, and consolidation of socialism throughout a large part of the world — there are only two possible paths for an independent nation: to return to imperialist domination (neo-colonialism, capitalism, state capitalism), or to take the way of socialism. (source)

Further:

The essential characteristic of our times is the general struggle of the peoples against imperialism and the existence of a socialist camp, which is the greatest bulwark against imperialism. (source)

In response to the question of to what extent Marxism and Leninism as an ideology had been relevant to the national liberation struggle of Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde, Cabral stated:

Moving from the realities of one’s own country towards the creation of an ideology for one’s struggle doesn’t imply that one has pretensions to be a Marx or a Lenin or any other great ideologist, but is simply a necessary part of the struggle. I confess that we didn’t know these great theorists terribly well when we began. We didn’t know them half as well as we do now. We needed to know them, as I’ve said in order to judge in what measure we could borrow from their experience to help our situation – but not necessarily to apply the ideology blindly just because it’s very good. This is where we stand on this. (source)

Cabral’s writings on the class structure of Guinea-Bissaun and Capeverdian society are fascinating and deserve to be studied in detail. Here is a particularly interesting passage on the problem of trying to create a working class mentality in a country that only had a tiny working class:

We were faced with another difficult problem: we realised that we needed to have people with a mentality which could transcend the context of the national liberation struggle, and so we prepared a number of cadres from the group I have just mentioned, some from the people employed in commerce and other wage-earners, and even some peasants, so that they could acquire what you might call a working class mentality. You may think this is absurd – in any case it is very difficult; in order for there to be a working class mentality the material conditions of the working class should exist, a working class should exist. In fact we managed to inculcate these ideas into a large number of people – the kind of ideas which there would be if there were a working class. We trained about 1,000 cadres at our party school in Conakry, in fact for about two years this was about all we did outside the country. When these cadres returned to the rural areas they inculcated a certain mentality into the peasants and it is among these cadres that we have chosen the people who are now leading the struggle.” (source)

Speaking at a seminar on ‘Lenin and National Liberation’, held at Alma Ata, capital of Soviet Socialist Republic of Kazakhstan, in 1970, Cabral made the crucial connection between Lenin’s ideas and the national liberation struggles being waged across Africa:

“How is it that we, a people deprived of everything, living in dire straits, manage to wage our struggle and win successes? Our answer is: this is because Lenin existed, because he fulfilled his duty as a man, a revolutionary and a patriot. Lenin was and continues to be, the greatest champion of the national liberation of the peoples.” (source)

Yusuf Dadoo’s obituary of Cabral notes that “he had very close association with the Soviet Union which he visited on many occasions and made a major contribution to the promotion and strengthening of friendship and cooperation between the peoples of Guinea-Bissau and the Soviet Union, between the PAIGC and the CPSU.”

The socialist countries and the liberated African states were the major suppliers of weapons, training and finance to the PAIGC (as indeed they were to the MPLA in Angola, Frelimo in Mozambique, SWAPO in Namibia, ZANU and ZAPU in Zimbabwe, and the ANC and SACP in South Africa).

A socialist camp has arisen in the world. This has radically changed the balance of power, and this socialist camp is today showing itself fully conscious of its duties, international and historic, but not moral, since the peoples of the socialist countries have never exploited the colonised peoples. They are showing themselves conscious of their duty, and this is why I have the honour of telling you openly here that we are receiving substantial and effective aid from these countries, which is reinforcing the aid which we receive from our African brothers. If there are people who don’t like to hear this, let them come and help us in our struggle too. (source)

Further:

We want to mention the special aid given to us by the peoples of the socialist countries. We believe that this aid is a historic obligation, because we consider that our struggle also constitutes a defence of the socialist countries. And we want to say particularly that the Soviet Union, first of all, and China, Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, and other socialist countries continue to aid us, which we consider very useful for the development of our armed struggle. We also want to lay special emphasis on the untiring efforts – sacrifices that we deeply appreciate – that the people of Cuba – a small country without great resources, one that is struggling against the blockade by the US and other imperialists – are making to give effective aid to our struggle. For us, this is a constant source of encouragement, and it also contributes to cementing more and more the solidarity between our Party and the Cuban Party, between our people and the Cuban people, a people that we consider African. And it is enough to see the historical, political, and blood ties that unite us to be able to say this. Therefore, we are very happy with the aid that the Cuban people give us, and we are sure that they will continue increasing their aid to our national liberation struggle in spite of all difficulties. (source)

Anti-imperialist unity

Amílcar Cabral was a consummate internationalist, who understood anti-imperialist unity not simply in abstract intellectual terms but as a matter of life and death for his movement. After all, the enemy has shown itself to be very capable of developing unity when it needs to:

The Portuguese government has managed to guarantee for as long as necessary the assistance which it receives from the Western powers and from its racist allies in Southern Africa. It is our duty to stress the international character of the Portuguese colonial war against Africa and the important and even decisive role played by the USA and Federal Germany in pursuing this war. If the Portuguese government is still holding out on the three fronts of the war which it is fighting in Africa, it is because it can count on the overt or covert support of the USA, freely use NATO weapons, buy B26 aircraft for the genocide of our people (including from ‘private parties’), and obtain whenever it wishes money. jet aircraft and weapons of every sort from Federal Germany where, furthermore, certain war-wounded from the Portuguese colonial army are hospitalised and treated. (source)

In a fiery opening address at the conference of the Conference of Nationalist Organizations of the Portuguese Colonies (CONCP) held in Dar Es-Salaam in 1965, we see the breadth and depth of his internationalism:

Our hearts beat in unison with the hearts of our brothers in Vietnam who are giving us a shining example by facing the most shameful and unjustifiable aggression of the US imperialists against the peaceful people of Vietnam. Our hearts are equally with our brothers in the Congo who, in the bush of that vast and rich African country are seeking to resolve their problems in the face of imperialist aggression and of the manoeuvres of imperialism through their puppets. That is why we of the CONCP proclaim loud and clear that we are against Tshombe, against all the Tshombes of Africa. Our hearts are also with our brothers in Cuba, who have shown that even when surrounded by the sea, a people is capable of taking up arms and successfully defending its fundamental interests and of deciding its own destiny. We are with the Blacks of North America, we are with them in the streets of Los Angeles, and when they are deprived of all possibility of life, we suffer with them.

We are with the refugees, the martyrised refugees of Palestine, who have been tricked and driven from their own homeland by the manoeuvres of imperialism. We are on the side of the Palestinian refugees and we support wholeheartedly all that the sons of Palestine are doing to liberate their country, and we fully support the Arab and African countries in general in helping the Palestinian people to recover their dignity, their independence and their right to life. We are also with the peoples of Southern Arabia, of so-called ‘French’ Somaliland, of so-called ‘Spanish’ Guinea, and we are also most seriously and painfully with our brothers in South Africa who are facing the most barbarous racial discrimination. We are absolutely certain that the development of the struggle in the Portuguese colonies, and the victory we are winning each day over Portuguese colonialism is an effective contribution to the elimination of the vile, shameful regime of racial discrimination, of apartheid in South Africa. And we are also certain that peoples like that of Angola, that of Mozambique and ourselves in Guinea and Cabo Verde, far from South Africa, will soon, very soon we hope, be able to play a very important role in the final elimination of that last bastion of imperialism and racism in Africa, South Africa. (source)

On Palestine:

We have as a basic principle the defence of just causes. We are in favour of justice, human progress, the freedom of the people. On this basis we believe that the creation of Israel, carried out by the imperialist states to maintain their domination in the Middle East, was artificial and aimed at the creation of problems in that very important region of the world. This is our position: the Jewish people have lived in different countries of the world. We lament profoundly what the Nazis did to the Jewish people, that Hitler and his lackeys destroyed almost six million during the last World War. But we do not accept that this gives them the right to occupy a part of the Arab nation. We believe that the people of Palestine have a right to their homeland. We therefore think that all the measures taken by the Arab peoples, by the Arab nation, to recover the Palestinian Arab homeland are justified. (source)

On Vietnam:

For us, the struggle in Vietnam is our own struggle. We consider that in Vietnam not only the fate of our own people but also that of all the peoples struggling for their national independence and sovereignty is at stake. We are in solidarity with the people of Vietnam, and we immensely admire their heroic struggle against US aggression and against the aggression of the reactionaries of the southern part of Vietnam, who are no more than the puppets of US imperialism. (ibid)

Visiting the US, Cabral met with representatives from a number of black liberation groups, and demonstrated a solid understanding of, and solidarity with, their struggle.

You can be sure that we realize the difficulties you face, the problems you have and your feelings, your revolts, and also your hopes. We think that our fighting for Africa against colonialism and imperialism is a proof of understanding of your problem and also a contribution for the solution of your problems in this continent. Naturally the inverse is also true. All the achievements towards the solution of your problems here are real contributions to our own struggle. And we are very encouraged in our struggle by the fact that each day more of the African people born in America become conscious of their responsibilities to the struggle in Africa.

We think that all you can do here to develop your own conditions in the sense of progress, in the sense of history and in the sense of the total realization of your aspirations as human beings is a contribution for us. It is also a contribution for you to never forget that you are Africans. (source)

He also makes an important point about the politics of non-alignment, specifying that this doesn’t mean “neither east nor west”, or “neither capitalism nor socialism”, but rather retaining independence of decision making:

Non-alignment for us means not aligning ourselves with blocs, not aligning ourselves with the decisions of others. We reserve the right to make our own decisions, and if by chance our choices and decisions coincide with those of others, that is not our fault. We are for the policy of non-alignment, but we consider ourselves to be deeply committed to our people and committed to every just cause in the world. We see ourselves as part of a vast front of struggle for the good of humanity. (source)

Cuba

In his incredible book ‘Conflicting Missions’, Piero Gleijeses writes in some detail about the relationship between Cuba and Guinea Bissau:

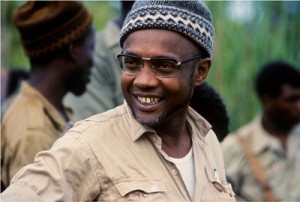

In January 1966, Cabral made his first trip to Cuba when he led the PAIGC delegation to the Tricontinental Conference in Havana. He was ‘the most impressive African in attendance,’ U.S. intelligence reported, and he made a powerful impression on his Cuban hosts. ‘His address to the Tricontinental was brilliant,’ Risquet remembered. ‘Everyone was struck by his great intelligence and personality. Fidel was very impressed by him’…

Amilcar Cabral had decided that Cuba alone should send its fighters to Guinea-Bissau. He chose Cuba in part because he felt some cultural and ethnic affinity with the Cubans and, above all, because he respected the Cuban revolution. ‘I remember that when I was in Cuba, Fidel told me that Cuba is also Africa,’ he told a group of Cubans in August 1966. ‘I don’t believe there is life after death, but if there is, we can be sure that the souls of our forefathers who were taken away to America to be slaves are rejoicing today to see their children reunited and working together to help us be independent and free.’ Thirty years later, other PAIGC leaders echoed his words. ‘We greatly admired the struggle of the Cuban people. The Cubans were a special case because we knew that they, more than anyone else, were the champions of internationalism,’ one recalled. ‘Cuba made no demands, it gave us unconditional aid,’ said another.

It was the Soviet bloc whose help was decisive. It provided arms, educational opportunities, and other material and political support. The Soviet Union was, by far, the major source of weapons. Cuba, too, gave material help, in the form of supplies, military training in Cuba, and scholarships. This was a considerable and generous effort for a poor country. But Cuba did much more, and its role was unique. Only Cubans fought in Guinea Bissau alongside the guerrilla fighters of the PAIGC…

Luis Cabral (Amilcar’s brother) later stated: ‘We were able to fight and triumph because other countries and people helped us … with weapons, with medicine, with supplies… But there is one nation that in addition to material, political, and diplomatic support, even sent its children to fight by our side, to shed their blood in our land alongside that of the best children of our country. This great people, this heroic people, we all know that is the heroic people of Cuba; the Cuba of Fidel Castro; the Cuba of the Sierra Maestra, the Cuba of Moncada… Cuba sent its best sons here to help us in the technical aspects of our war, to help us wage this great struggle against Portuguese colonialism.’

Visiting Cuba in 1966, Cabral stated:

If any of us came to Cuba with doubts in our mind about the solidity, strength, maturity and vitality of the Cuban Revolution, these doubts have been removed by what we have been able to see. Our hearts are now warmed by an unshakeable certainty which gives us courage in the difficult but glorious struggle against the common enemy: no power in the world will be able to destroy this Cuban Revolution, which is creating in the countryside and in the towns not only a new life but also — and even more important — a New Man, fully conscious of his national, continental and international rights and duties…

We guarantee that we, the peoples of the countries of Africa, still completely dominated by Portuguese colonialism, are prepared to send to Cuba as many men and women as may be needed to compensate for the departure of those who for reasons of class or of inability to adapt have interests or attitudes which are incompatible with the interests of the Cuban people. Taking once again the formerly hard and tragic path of our ancestors (mainly from Guinea and Angola) who were taken to Cuba as slaves, we would come now as free men, as willing workers and Cuban patriots, to fulfill a productive function in this new, just and multi-racial society, and to help and defend with our own lives the victories of the Cuban people. Thus we would strengthen both all the bonds of history, blood and culture which unite our peoples with the Cuban people, and the spontaneous giving of oneself, the deep joy and infectious rhythm which make the construction of socialism in Cuba a new phenomenon for the world, a unique and, for many, unaccustomed event. (source)

Solidarity with the working class movement in the ‘first world’

Cabral never tired of highlighting the need for global solidarity and unity against imperialism – a unity that should include the oppressed classes within imperialist society itself. However, he understood from direct experience that the creation of a ‘labour aristocracy’ had the effect of vastly reducing the anti-imperialist sentiment of the working class in western Europe and North America. Frankly, he understood this phenomenon better than 90% of western leftists.

I should just like to make one last point about solidarity between the international working class movement and our national liberation struggle. There are two alternatives: either we admit that there really is a struggle against imperialism which interests everybody, or we deny it. If, as would seem from all the evidence, imperialism exists and is trying simultaneously to dominate the working class in all the advanced countries and smother the national liberation movements in all the underdeveloped countries, then there is only one enemy against whom we are fighting. If we are fighting together, then I think the main aspect of our solidarity is extremely simple: it is to fight…

We are struggling in Guinea with guns in our hands, you must struggle in your countries as well – I don’t say with guns in your hands, I’m not going to tell you how to struggle, that’s your business; but you must find the best means and the best forms of fighting against our common enemy: this is the best form of solidarity. There are, of course, other secondary forms of solidarity: publishing material, sending medicine, etc; I can guarantee you that if tomorrow we make a breakthrough and you are engaged in an armed struggle against imperialism in Europe we will send you some medicine too. (source)

Interestingly, Cabral saw imperialism as being a greater threat to the European working class than to the masses of the oppressed nations – while revolutionising the latter, it had pacified the former, ”encouraging the development of a privileged proletariat and thus lowering the revolutionary level of the working classes.”

As we see it, neocolonialism (which we may call rationalised imperialism) is more a defeat for the international working class than for the colonised peoples. Neocolonialism is at work on two fronts – in Europe as well as in the underdeveloped countries. Its current framework in the underdeveloped countries is the policy of aid, and one of the essential aims of this policy is to create a false bourgeoisie to put a brake on the revolution and to enlarge the possibilities of the petty bourgeoisie as a neutraliser of the revolution; at the same time it invests capital in France, Italy, Belgium, England and so on. In our opinion the aim of this is to stimulate the growth of a workers’ aristocracy, to enlarge the field of action of the petty bourgeoisie so as to block the revolution. (ibid)

In his overview of class society in Guinea Bissau, he notes that the settlers of working class origin are often the most reactionary. This is another manifestation of the success of the western ruling classes in brainwashing workers.

The European settlers are, in general, hostile to the idea of national liberation; they are the human instruments of the colonial state in our country and they therefore reject a priori any idea of national liberation there. It has to be said that the Europeans most bitterly opposed to the idea of national liberation are the workers, while we have sometimes found considerable sympathy for our struggle among certain members of the European petty bourgeoisie. (ibid)

Talking with a degree of frustration about the endless criticism meted out to the liberation struggles by left sects in Europe, he says:

The criticism reminds me of a story about some lions: there is a group of lions who are shown a picture of a lion lying on the ground and a man holding a gun with his foot on the lion (as everybody knows the lion is proud of being king of the jungle); one of the lions looks at the picture and says, “if only we lions could paint”. If only one of the leaders of one of the new African countries could take time off from the terrible problems in his own country and become a critic of the European left and say all he had to say about the retreat of the revolution in Europe, of a certain apathy in some European countries and of the false hopes which we have all had in certain European groups… (ibid)

Against dogmatism

Amílcar Cabral is famous for his insistence on a concrete approach to concrete problems, rather than the dogmatic application of formulas. He was by no means against ideology, but he was adamant that no set of revolutionary principles could simply be transplanted wholesale from one situation to another. English historian, Africanist and the major chronicler of the Guinea-Bissau revolution Basil Davidson wrote that “if one had to define a single influential aspect of Cabral’s approach, perhaps it would be his insistence on the study of reality. ‘Do not confuse the reality you live in with the ideas you have in your head’, was a favourite theme in his seminars for party militants. Your ideas may be good, even excellent, but they will be useless ideas unless they spring from and interweave with the reality you live in. What is necessary is to see into and beyond appearances: to free yourself from the sticky grasp of ‘received opinions’, whether academic or otherwise. Only through a principled study of reality, of the strictly here and now, can a theory of revolutionary change be integrated with its practice to the point where the two become inseparable. This is what he taught.” (source)

After all, there were definitely no ready-made formulas ready for use in the context of Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde. These highly complex African societies, whose history had been diverted by centuries of oppression by a colonial power that was itself very backward and dependent, were hardly the revolutionary centres that Marx and Engels had in mind when they produced the Manifesto of the Communist Party in 1848. Mao Zedong’s groundbreaking application of Marxism to the conditions of semi-fuedal China provided a much closer analogy to the conditions prevailing in Guinea Bissau, but even then there were important differences that required concrete analysis.

Naturally, there are certain general or universal laws, even scientific laws for any condition, but the liberation struggle has to be developed according to the specific conditions of each country. This is fundamental. The specific conditions to be considered include economic, cultural, social, political and even geographic conditions. The guerrilla manuals once told us that without mountains you cannot make guerrilla war. But in my country there are no mountains, only the people. In the economic field we committed an error. We began training our people to commit sabotage on the railroads. When they returned from their training we remembered that there were no railroads in our country. The Portuguese built them in Mozambique and Angola but not in our country. (source)

The PAIGC made an extensive study of production relations in the countryside, which led them to a campaign of mobilising the peasantry that was decidedly different to what had taken place in other African and Asian countries.

It so happens that in our country the Portuguese colonialists did not expropriate the land; they allowed us to cultivate the land. They did not create agricultural companies of the European type as they did, for instance, in Angola, displacing masses of Africans in order to settle Europeans. We maintained a basic structure under colonialism – the land as co-operative property of the village, of the community. This is a very important characteristic of our peasantry, which was not directly exploited by the colonisers but was exploited through trade, through the differences between the prices and the real value of products. This is where the exploitation occurs, not in work, as happens in Angola with the hired workers and company employees. This created a special difficulty in our struggle – that of showing the peasant that he was being exploited in his own country.

Telling the people that “the land belongs to those who work on it” was not enough to mobilise them, because we have more than enough land, there is all the land we need. We had to find appropriate formulae for mobilising our peasants, instead of using terms that our people could not yet understand. We could never mobilise our people simply on the basis of the struggle against colonialism-that has no effect. To speak of the fight against imperialism is not convincing enough. Instead we use a direct language that all can understand:

“Why are you going to fight? What are you? What is your father? What has happened to your father up to now? What is the situation? Did you pay taxes? Did your father pay taxes? What have you seen from those taxes? How much do you get for your groundnuts? Have you thought about how much you will earn with your groundnuts? How much sweat has it cost your family? Which of you have been imprisoned? You are going to work on road-building: who gives you the tools? You bring the tools. Who provides your meals? You provide your meals. But who walks on the road? Who has a car? And your daughter who was raped-are you happy about that?” (source)

Class suicide

Given the near-absence of an industrial working class, and the prevalence of petty bourgeois (or middle class) elements in the leadership of the national liberation movement, Cabral talked of the need for the petty bourgeoisie to commit ‘class suicide’ in order that the gains of the revolution not be reversed.

To retain the power which national liberation puts in its hands, the petty bourgeoisie has only one path: to give free rein to its natural tendencies to become more bourgeois, to permit the development of a bureaucratic and intermediary bourgeoisie in the commercial cycle, in order to transform itself into a national pseudo-bourgeoisie, that is to say in order to negate the revolution and necessarily ally. In order not to betray these objectives the petty bourgeoisie has only one choice: to strengthen its revolutionary consciousness, to reject the temptations of becoming more bourgeois and the natural concerns of its class mentality, to identify itself with the working classes and not to oppose the normal development of the process of revolution. This means that in order to truly fulfill the role in the national liberation struggle, the revolutionary petty bourgeoisie must be capable of committing suicide as a class in order to be reborn as revolutionary workers, completely identified with the deepest aspirations of the people to which they belong. (source)

Armed struggle

The people of Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde fought for the independence – successfully – with guns in hand (and, thanks primarily to the Soviet Union, with sophisticated military technology). However, Cabral never romanticised the armed struggle and the loss of human life.

The past and present experiences of various peoples, the present situation of national liberation struggles in the world (especially in Vietnam, the Congo and Zimbabwe) as well as the situation of permanent violence, or at least of contradictions and upheavals, in certain countries which have gained their independence by the so-called peaceful way, show us not only that compromises with imperialism do not work, but also that the normal way of national liberation, imposed on peoples by imperialist repression, is armed struggle.

I am not a great defender of the armed fight. I am myself very conscious of the sacrifices demanded by the armed fight. It is a violence against even our own people. But it is not our invention – it is not our cool decision; it is the requirement of history. This is not the first fight in our country, and it is not Cabral who invented the struggle. We are following the example of our grandfathers who fought against Portuguese domination 50 years ago. Today’s fight is a continuation of the fight to defend our dignity, our right to have an identity – our own identity.

If it were possible to solve this problem without the armed fight – why not?! But while the armed fight demands sacrifices, it also has advantages. Like everything else in the world, it has two faces – one positive and the other negative – the problem is in the balance. For us now, it (the armed fight) is a good thing in our opinion, and our condition is a good thing because this armed fight helped us to accelerate the revolution of our people, to create a new situation that will facilitate our progress. (ibid)

African history and culture

The colonists usually say that it was they who brought us into history: today we show that this is not so. They made us leave history, our history, to follow them, right at the back, to follow the progress of their history. Today, in taking up arms to liberate ourselves, in following the example of other peoples who have taken up arms to liberate themselves, we want to return to our history, on our own feet, by our own means and through our own sacrifices. (ibid)

In his speech at the first Tricontintal Conference in Havana, 1966, Cabral questions the idea put forward in the Communist Manifesto that “all history is the history of class struggle”, noting that this cuts pre-class society out of history.

Does history begin only with the development of the phenomenon of ‘class’, and consequently of class struggle? To reply in the affirmative would be to place outside history the whole period of life of human groups from the discovery of hunting, and later of nomadic and sedentary agriculture, to the organization of herds and the private appropriation of land. It would also be to consider — and this we refuse to accept — that various human groups in Africa, Asia, and Latin America were living without history, or outside history, at the time when they were subjected to the yoke of imperialism. It would be to consider that the peoples of our countries, such as the Balantes of Guinea, the Coaniamas of Angola and the Macondes of Mozambique, are still living today — if we abstract the slight influence of colonialism to which they have been subjected — outside history, or that they have no history. (source)

In place of class struggle as the driving force of all history, Cabral proposes instead the development of the means of production:

If class struggle is the motive force of history, it is so only in a specific historical period. This means that before the class struggle — and necessarily after it, since in this world there is no before without an after — one or several factors was and will be the motive force of history. It is not difficult to see that this factor in the history of each human group is the mode of production — the level of productive forces and the pattern of ownership — characteristic of that group. Furthermore, as we have seen, classes themselves, class struggle and their subsequent definition, are the result of the development of the productive forces in conjunction with the pattern of ownership of the means of production. It therefore seems correct to conclude that the level of productive forces, the essential determining element in the content and form of class struggle, is the true and permanent motive force of history…

Eternity is not of this world, but man will outlive classes and will continue to produce and make history, since he can never free himself from the burden of his needs, both of mind and of body, which are the basis of the development of the forces of production.

Through this logic, Cabral seeks to break the inferiority complex that is pushed onto the masses of the oppressed nations by colonial ideology, and reassert Africa’s place in history. He also uses this theory to situate the national liberation struggle within the movement of history toward socialism: colonial domination has actually retarded the development of the productive forces (this is especially the case for Portugal’s colonies) and is a block on progress.

Both in colonialism and in neo-colonialism the essential characteristic of imperialist domination remains the same: the negation of the historical process of the dominated people by means of violent usurpation of the freedom of development of the national productive forces.

The colonies must remove this block and, in the interests of rapid development, align themselves with the socialist states:

Whatever its level of productive forces and present social structure, a society can pass rapidly through the defined stages appropriate to the concrete local realities (both historical and human) and reach a higher stage of existence. This progress depends on the concrete possibilities of development of the society’s productive forces and is governed mainly by the nature of the political power ruling the society… A more detailed analysis would show that the possibility of such a jump in the historical process arises mainly, in the economic field, from the power of the means available to man at the time for dominating nature, and, in the political field, from the new event which has radically changed the face of the world and the development of history, the creation of socialist states.

He also notes the process of intense human development that takes place within the national liberation struggle itself:

Our national liberation struggle has a great significance both for Africa and for the world. We are in the process of proving that peoples such as ours – economically backward, living sometimes almost naked in the bush, not knowing how to read or write, not having even the most elementary knowledge of modern technology – are capable, by means of their sacrifices and efforts, of beating an enemy who is not only more advanced from a technological point of view but also supported by the powerful forces of world imperialism. Thus before the world and before Africa we ask: were the Portuguese right when they claimed that we were uncivilised peoples, peoples without culture? We ask: what is the most striking manifestation of civilisation and culture if not that shown by a people which takes up arms to defend its right to life, to progress, to work and to happiness? (source)

Cabral was also strongly focused on the role of cultural imperialism in suppressing the peoples of the oppressed nations, and the importance of culture as an element of resistance to imperialism:

A people who free themselves from foreign domination will be free culturally only if, without complexes and without underestimating the importance of positive accretions from the oppressor and other cultures, they return to the upward paths of their own culture, which is nourished by the living reality of its environment, and which negates both harmful influences and any kind of subjection to foreign culture. Thus, it may be seen that if imperialist domination has the vital need to practice cultural oppression, national liberation is necessarily an act of culture”

The value of culture as an element of resistance to foreign domination lies in the fact that culture is the vigorous manifestation on the ideological or idealist plane of the physical and historical reality of the society that is dominated or to be dominated. Culture is simultaneously the fruit of a people’s history and a determinant of history, by the positive or negative influence which it exerts on the evolution of relationships between man and his environment, among men or groups of men within a society, as well as among different societies. (source)

Although he stressed the importance of African culture and identity, Cabral always made clear that this was not based on any type of discrimination or feelings of superiority.

We are not racists. We are fundamentally and deeply against any kind of racism. Even when people are subjected to racism we are against racism from those who have been oppressed by it. In our opinion – not from dreaming but from a deep analysis of the real condition of the existence of mankind and the division of societies – racism is a result of certain circumstances. It is not eternal in any latitude in the world. It is the result of historical and economic conditions. And we cannot answer racism with racism. It is not possible. In our country, despite some racist manifestations by the Portuguese, we are not fighting against the Portuguese people or whites. We are fighting for the freedom of our people – to free our people and to allow them to be able to love any kind of human being. You cannot love when you are a slave… In combating racism we don’t make progress if we combat the people themselves. We have to combat the causes of racism. If a bandit comes into my house and I have a gun I cannot shoot the shadow of this bandit. I have to shoot the bandit. Many people lose energy and effort, and make sacrifices combating shadows. (source)

Further reading

Needless to say, a selection of quotes can only serve as an outline of, and introduction to, the political, cultural and philosophical thought of Amílcar Cabral. Some other material that you may find useful:

- Speech: The Weapon of Theory

- Article: Tell no lies, Claim no easy victories

- Speech: The Nationalist Movements of the Portuguese Colonies

- Speech: Brief Analysis of the Social Structure in Guinea

- Speech: Connecting the struggles: An informal chat with black Americans

- Obituary by Yusuf Dadoo: Amilcar Cabral – Outstanding Leader Of African Liberation Movement

- Article by Ama Biney: Cabral at 90: Unity and struggle continue in Africa

- Selected quotes (blog): Return to the Source

- Article by Danny Shaw: Amilcar Cabral and the national liberation movement of Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde

- Book: Unity and Struggle (Speeches and Writings of Amilcar Cabral)

- Book: Return to the Source (Selected Speeches of Amilcar Cabral)

- Book: Basil Davidson – No Fist is Big Enough to Hide the Sky

- Book: Reiland Rabaka – Concepts of Cabralism: Amilcar Cabral and Africana Critical Theory

- Book: Patrick Chabal – Amílcar Cabral: Revolutionary leadership and people’s war

- Book: Piero Gleijeses – Conflicting Missions