This article first appeared in the Morning Star on 23 August 2018.

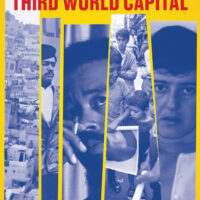

ALGIERS, Third World Capital is a fascinating, vibrant, endearing and engaging memoir, providing fresh insight into some important episodes of the second half of the 20th century.

Elaine Mokhtefi, a white North American woman of Jewish heritage, became involved in politics at university, becoming an activist in the World Assembly of Youth (WAY), an organisation committed to global government and world peace. Moving to Paris in the 1950s, she was introduced to the Algerian liberation struggle via the emigre Algerian population in that city.

An interpreter and organiser for WAY and later the Algerian government in exile, she worked with and befriended some of the giants of the anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggles, including Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere, Martinique-born Algerian revolutionary Frantz Fanon, African-American revolutionary Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), ANC president Oliver Tambo and Swapo leader Sam Nujoma.

Deeply involved in the Algerian solidarity movement and committed to the project of building a new, socialist-oriented society on the ashes of the French colonial project, Mokhtefi went to live in Algiers soon after independence in 1962. Algeria in that period was a tremendously exciting place, a new state defined by its heroic and extraordinary struggle against a vicious French occupation.

The countries that had supported the war of resistance — Yugoslavia, Cuba, China, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, the Soviet Union and others — were now Algeria’s main allies and sent advisers and experts to work with the new government. The liberation movements from Angola, Mozambique, South Africa, Vietnam and Palestine were welcomed with open arms. Today, Algeria’s diplomacy is more nuanced, but, in the early years after liberation from French colonialism, it was the centre of gravity of the anti-imperialist world.

One little-known manifestation of Algeria’s status as “Third World capital” is its support for progressive movements within the “First World,” most notably the black liberation struggle in the US.

Mokhtefi writes that “Algeria adopted an open-door policy of aid to the oppressed, an invitation to liberation and opposition movements and personalities from around the world.” Providing resources and recognition to the Black Panther Party, then at the zenith of its fame and activity, “flowed naturally from [Algeria’s] position as a Third World leader.”

Mokhtefi was closely involved in the establishment of the International Section of the Black Panther Party. Assigned to assist and interpret for Eldridge Cleaver from the moment of his arrival, she was for several years in almost daily contact with Cleaver, his then wife Kathleen, Don Cox and other leading activists.

As such, she is uniquely well-positioned to tell the little-known story of the Black Panthers in Algeria — how they operated, interacted with Algerian society and the government and particularly how they were affected by the 1971 split in the Black Panther Party.

The split remains a highly controversial topic. Cleaver’s version of events hasn’t been helped over the years by his fondness for self-serving exaggeration and deception, not to mention his political descent into Republican conservatism, and Mokhtefi isn’t under any illusions about him.

However, she gives a convincing description of what the split looked like from the Algiers Panthers’ point of view.

The story as it is usually told has Eldridge as an ultra-left militant, pushing for an escalation of the underground armed struggle, whereas party leader Huey Newton favoured a programme based on community activism.

In Mokhtefi’s telling, however, the split was based primarily on Newton’s increasingly erratic, violent and obsessive behaviour, with the FBI merrily adding fuel to the fire. Her version of events may anger some Panther veterans, but it’s a valid contribution to the historical record.

Mokhtefi also discusses some of the challenges that faced post-colonial Algeria, a country in which between 300,000 and 500,000, out of a population of nine million, had been killed during the war of liberation and where departing French soldiers and settlers burned villages and books. The adult literacy rate was under 10 per cent and there were not more than 500 university graduates.

The victorious National Liberation Front had to perform miracles in order to reverse the effects of colonialism, war and imposed underdevelopment.

The near-impossible nature of the problems at hand inevitably led to a certain amount of despondency and infighting, the most prominent example of which is the coup that brought Houari Boumediene to power and sent first president Ahmed Ben Bella to prison. Considering the effect on her own life — Mokhtefi ended up being deported as a result of her friendship with Ben Bella’s wife — she discusses the coup in surprisingly balanced and dispassionate terms, contextualising it within the intensely difficult and fraught situation Algeria was subjected to.

This exciting memoir is an important story and it’s told with skill, humour and humility.