This wasn’t supposed to happen. When Jeremy Corbyn announced, a few months ago, that he was throwing his hat in the ring for the Labour leadership contest, many – myself included – were sceptical. The whole project seemed irrelevant and hopeless; even if he did get sufficient MP nominations to get on the ballot, everybody knew that his candidature would end in ignominious defeat. The episode was set to provide yet more proof (as if any were needed) that the entire ‘left Labour’ project was long past its sell-by date.

The bookmakers, whose predictions are generally far more reliable than those of the left commentariat, gave Corbyn odds of 200-1 against (thereby producing quite a windfall for a few startlingly over-optimistic British socialists).

Then something very strange and unprecedented happened; something that nobody could have predicted. Ordinary people around the country became interested in the campaign, excited at the possibility – no matter how remote – of having an old-fashioned leftist as leader of the opposition. Thousands of people joined the Labour Party. Tens of thousands signed up as registered supporters, specifically in order to vote for Corbyn. The unfaltering vitriol of the mainstream press – including much of its supposedly left-leaning branch – and the impassioned pleas of Blair, Brown and the rest of the Labour grandees proved totally ineffective in stemming the tide of popular support for the Corbyn campaign (in the case of Blair and Mandelson, their contributions only served to heighten Corbyn’s popularity!). Huge numbers of people signed up to help out, manning phone lines, distributing leaflets, building websites, spreading the word on social media.

Corbyn’s campaign meetings, nearly a hundred of them, were all packed. Many times he had to address overspill rooms – including, in London, speaking to a crowd outside from atop a fire engine provided by the Fire Brigades Union. The buzz surrounding the campaign was reminiscent of the excitement surrounding the Scottish independence referendum last year. For many young people in England, the Corbyn leadership campaign represented the first time in their lives that anything within the realm of mainstream politics had felt interesting, relevant and worthy of their participation. The result was a landslide victory for Corbyn, the election of the most left-wing leader in Labour’s history, and a reversal of many decades of near-universal conservatism in the general political narrative.

There are too many variables to predict what will happen in the coming months and years, but what we can say for sure is that the emergence of a socialist, anti-monarchist, anti-Nato, anti-nuclear, anti-war, anti-racist, anti-neoliberal, veteran campaigner as leader of the parliamentary opposition in Britain is a hugely significant moment. As Seumas Milne notes: “By any reckoning, Corbyn’s election and the movement that delivered it represent a political eruption of historic proportions. The political conformity entrenched during the years of unchallenged neoliberalism has been broken.”

Why did Corbyn win?

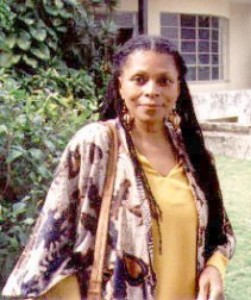

What has changed? How is it possible that veteran left-winger Jeremy Corbyn could win the Labour leadership in 2015 – by a landslide – when veteran left-winger Diane Abbott only received 7% of the votes in 2010, or when veteran left-winger John McDonnell couldn’t get sufficient nominations to stand against Gordon Brown in 2007, or when veteran left-winger Tony Benn was defeated by an embarrassing margin in 1983?

There are a few key aspects that need to be considered.

-

Vast swathes of people are feeling more and more alienated, and are struggling economically to an ever greater degree. People have increasingly had enough of the vindictive neoliberalism that has dominated British politics for so long. The policies of ‘austerity’ are starting to impact people’s livelihoods in a very real way. Those hit worst are the most vulnerable, oppressed and disenfranchised: the immigrants, ethnic minorities, low-paid workers, casual workers, unemployed, disabled. But there is also a significant layer of the middle class that is being ‘proletarianised’ – no longer can people expect free education and a range of decent employment opportunities to choose from after university; nor can they expect any sort of affordable housing. A clear majority now faces declining living standards and prospects for the future, and Corbyn’s plain-speaking anti-austerity platform speaks to the needs of that majority far more effectively than the Tories, Lib Dems or New Labourites.

-

The last general election was a wake-up call. The resounding failure of Ed Miliband’s half-hearted, apologetically centre-left stance made it all too clear that people are not interested in a political process where, as Craig Murray puts it, “if the range of possible political programmes were placed on a linear scale from 1 to 100, the Labour and Conservative parties offer you the choice between 81 and 84.” The result of Labour’s pathetic platform is that we’ve ended up with “one of the most uncaring, uncompromising and out of touch governments that the UK has seen since Thatcher”. Furthermore, the Scottish independence referendum and the SNP’s extraordinary performance north of the border in the general election amply demonstrated that there is an appetite for anti-austerity, anti-war, left-of-Labour politics; that to adopt progressive stances is not to be unelectable.

-

There is emerging, belatedly, an understanding of the profoundly elitist and anti-popular nature of neoliberalism – the ‘free market’ capitalism that promotes economic growth via unrestrained exploitation. Twenty years ago, with the Soviet Union and its East European allies out of the way, and with a globalised ‘end of history’ declared, international capital no longer felt the need to pander even to the relatively tame social democracy offered by the likes of the Labour left. This was shoved aside in favour of a Thatcherite neoliberalism that, in the words of Stuart Hall, “evolved a broad hegemonic basis for its authority, deep philosophical foundations, as well as an effective popular strategy; that was… grounded in a radical remodelling of state and economy and a new neo-liberal common sense.” The workers and oppressed were deemed irrelevant. Mainstream politics was converted into the undisguised (as opposed to somewhat disguised) representation of the finance capitalist elite.

More recently, in response to a massive global recession for which the poor have been made to pay (while the banks are bailed out to the tune of trillions of dollars), a global fightback against neoliberalism has finally started to grow. This movement has been spearheaded by the wave of progressive governments in Latin America, but is also expressed in different ways by, for example, the rise of the Occupy movement; the coming to power of the Syriza government in Greece; the increasing popularity of Sinn Fein, SNP, Podemos, Die Linke, the Portuguese Communist Party, Portugal’s Left Bloc and other forces. This is the global context in which Corbyn’s victory should be understood.

On top of all that, the people around Corbyn have waged a highly effective and energetic campaign that has tapped into popular sentiment, building a momentum that has proven incredibly resilient in the face of the slander campaign being waged by the mainstream press.

It certainly helps that, in a political world that has become synonymous with corruption, dishonesty, spin, inhumanity and cynical self-interest, Corbyn stands out among mainstream politicians as being consistently principled, genuine, compassionate and honest. He’s a life-long activist against the worst injustices of capitalism, against racism, and against war. He has campaigned for policies that most reasonable people agree with: against wars, against austerity, against the bedroom tax, against privatisation, for taxing the rich, for a living wage, for the NHS, for welcoming refugees. As an MP over three decades, he has an admirable record of standing up for the poor and marginalised.

What does Corbyn stand for?

Corbyn’s election victory and the hype surrounding his campaign are more a reflection of Corbyn as an individual than of the Labour Party as such. The term ‘Corbynmania’ expresses this fairly clearly; after all, what other Labour leader can you imagine inspiring such a level of ‘mania’? Labour’s deeply uninspiring election platform was roundly rejected by the voters in May, handing David Cameron a majority government. ‘Corbynmania’ has arisen in spite of, rather than because of, the Labour Party’s record, and indeed it wouldn’t have been possible were it not for Corbyn’s record of voting against the party whip.

So to the extent that people are inspired by Jeremy Corbyn, what sort of political consciousness does this represent? What is the political framework associated with Corbyn?

The policies Corbyn is best known for are: opposing austerity; supporting the poor; supporting immigrants; opposing racism; protecting welfare; opposing war; opposing nuclear weapons; promoting re-nationalisation of key areas of the economy; protecting trade union rights; building social housing; ending homelessness; supporting public education and healthcare; exiting NATO; working for a united Ireland; supporting Palestine and progressive Latin America.

Corbyn isn’t proposing the overthrow of capitalism (more’s the pity!). His economic programme is not based on putting an end to the system of exploitation of man by man; rather, it expresses an anti-neoliberal vision that shifts the burden of crisis from the oppressed to the oppressors and which puts an end to savage cuts. His manifesto calls – in somewhat fluffy style – for “a fairer, kinder Britain based on innovation, decent jobs and decent public services.” Cuts should be reversed, important industries should be (re-)nationalised, the rich should pay their taxes, and cash should be printed in order to fund infrastructure spending.

Hardly extreme. As economist Michael Burke points out: “Jeremy Corbyn is the only candidate who is NOT proposing extremist economics. His policy aims to promote growth through increased public investment, funded by progressive reform of the current taxation system, and attacking the abuses of the £93 billion in annual payments for ‘corporate welfare’ in subsidies, bribes and incentives to the private sector. At the same time he opposes any attempt to make workers and the poor pay for the crisis and rightly argues that the deficit would close naturally with stronger growth”.

Corbyn’s appointment of Thomas Piketty, Ann Pettifor and Joseph Stigiltz to his economic advisory team indicates that his agenda is about building a credible consensus – within the framework of capitalist economics – for Keynesianism and against austerity. While this is by no means a Marxist programme, it represents a significant break with anything put forward by the political mainstream, and is clearly unacceptable to bulk of the British ruling class, which has worked feverishly to establish neoliberalism as an ideological norm, and which is irretrievably hostile to redistributive economics of any sort.

Foreign policy is another area where Corbyn’s platform resonates with a huge number of British people who oppose Britain’s wars of domination. His leadership election pledge on foreign policy reads:

No more illegal wars; a foreign policy that prioritises justice and assistance. Replacing Trident not with a new generation of nuclear weapons but jobs that retain the communities’ skills.

Corbyn is strongly opposed to any British military involvement in Syria, which the Cameron government is pushing strongly for. He correctly notes that a western bombing campaign actually feeds into the growth of Isis (“I don’t think going on a bombing campaign in Syria is going to bring about their defeat. I think it would make them stronger.”). He has also said that Labour should apologise for the destruction of Iraq, and suggested that Tony Blair could be convicted of war crimes. He opposes Britain’s membership of Nato and the west’s increasingly hostile position vis-a-vis Russia, noting that Nato has been “the major driver for the remilitarisation of central Europe”. He believes that “Britain’s role in international affairs needs to change to the promotion of conflict resolution and co-operation rather than using UK forces to achieve regime change”.

Being ‘tough on immigration’ is considered essential for anyone hoping to be elected to a position of power in England. Pandering to a racist, xenophobic, scape-goating agenda is par for the course – as exemplified by Labour’s notorious anti-immigration mug that appeared in the run-up to the last general election. In that context, Jeremy’s pro-immigration and pro-refugee stance is a breath of fresh air and is something that has won him support. Pointing to the racism and hypocrisy implicit in the mainstream narrative on immigration, Corbyn asks in a recent interview: “Are we actually going to see sort of armed guards all around Europe keeping out the poor and the desperate? Some of whom are victims of impoverishment which is a product of a whole lot of economic circumstances. Some are victims of wars which we have been involved with such as Iraq and the bombing of Libya… At the end of the Second World War there was a coming together of all of the wealthy nations to accept very large numbers of refugees because they saw that as a humanitarian crisis. Is it different because so many of these people come from Africa as opposed to Europe?”

The class enemy goes berserk

Predictably, the mainstream media machine has gone into overdrive in its attempts to bury the movement building around Corbyn. Britain’s newspaper columns have, since the very beginning of the Labour leadership campaign, been given over to an army of Corbyn detractors, from the right-wing fruitcakes of the Daily Mail to the (bulk of the) supposedly left-liberal luvvies of the Guardian. In an almost touching display of unity, the defenders of the imperialist status quo have got together to publicly fret about the possibility of Corbyn’s election ushering in an era of “class hatred, the indulgence of unionised labour, and the Soviet-style handing out of favours to party loyalists on the council payrolls.”

Who better than Boris Johnson to state the case against Corbyn?

“Can this be happening? Are they really proposing that Her Majesty’s Opposition should be led by Jeremy Corbyn? He believes in higher taxes and a bigger deficit, and kowtowing to the unions, and abandoning all attempts to introduce competition or academic rigour in schools – let alone reforming welfare. He is a Sinn Fein-loving, monarchy-baiting, Israel-bashing believer in unilateral nuclear disarmament.”

The press have had a field day denouncing Corbyn over his long-standing relations with Sinn Fein; his support for revolutionary Venezuela; his involvement in the Stop the War Coalition, Cuba Solidarity Campaign and Palestine Solidarity Campaign; his stated belief that Hezbollah and Hamas are a necessary part of any valid Middle East peace process. The mad zionists of the Jewish Chronicle lost no time in slinging slanderous accusations of anti-semitism. But of course all this was nothing in comparison to the quantity of mud hurled when he appeared at a Battle of Britain commemoration and failed to sing along with God Save the Queen!

The press have had a field day denouncing Corbyn over his long-standing relations with Sinn Fein; his support for revolutionary Venezuela; his involvement in the Stop the War Coalition, Cuba Solidarity Campaign and Palestine Solidarity Campaign; his stated belief that Hezbollah and Hamas are a necessary part of any valid Middle East peace process. The mad zionists of the Jewish Chronicle lost no time in slinging slanderous accusations of anti-semitism. But of course all this was nothing in comparison to the quantity of mud hurled when he appeared at a Battle of Britain commemoration and failed to sing along with God Save the Queen!

David Cameron apparently worries that, “by leaving Nato, as Jeremy Corbyn suggests, or by comparing American soldiers to Isil … it will make Britain less secure.” Chancellor George Osborne believes that Corbyn’s election will create “an unholy alliance of Labour’s leftwing insurgents and the Scottish nationalists” that would pose a threat to Britain’s national security. It seems this is such a serious concern that there have even been rumblings of a military coup in the event that a Labour government was elected under Corbyn’s leadership.

The level of class hatred directed at Corbyn by the capitalist elite and their media tells us how much of a threat they seem him as.

Possibilities for the working class and oppressed

That the most left-wing, avowedly socialist member of parliament should be elected leader of the numerically largest political party in the country reflects a certain rising level of consciousness of the masses. In world-historic terms, this is still a long way from being a revolutionary consciousness, but ‘you can only start from where you are’. Every step forward is valuable and presents an opportunity for further advance. The sudden appearance of a leftist agenda at the very least creates space in which socialist and anti-imperialist voices can be heard, and in which radical ideas can flourish. For those who have lived through very tough decades of rightward drift in Britain and elsewhere, such space is clearly full of possibility. A recent statement by the US-based Party for Socialism and Liberation puts it well:

“Along with the dramatic rise of new mass movements against austerity throughout Europe, as well as progressive movements in the US, Latin America and elsewhere, it has become clear that the long period of reaction that began in the late 1970s and greatly accelerated under Margaret Thatcher in Britain and Ronald Reagan in the United States is drawing to a close. A new period of resistance to monopoly capitalism/imperialism is opening up, potentially leading to a revival of not only the trade unions but the revolutionary workers’ movement throughout the world. That this initial revival of anti-capitalism and socialism is being frequently, although not exclusively, expressed through the vehicle of electoral politics is to be expected in the first stage.”

What is perhaps most surprising is that such a progressive sentiment has attached itself to a Labour Party leadership contest. Arguably, this is to a certain degree coincidental. In different circumstances, a rising movement against neoliberalism and war might have attached itself to a process outside the Labour Party (as indeed it has done in Scotland), or it might not have found expression at all within mainstream politics. But the fact is that the left in England has not thus far been able to build a viable organisation to the left of Labour with the capacity to attract and mobilise large numbers of people; with the ability to tap into a spontaneously developing movement. Jeremy’s campaign arrived in the right place at the right time to provide a vehicle for a movement which, while ideologically diverse and lacking coherence, cohesion, strategy and leadership, is united by its opposition to neoliberalism, to austerity, to racism, to xenophobia and to war.

To what extent meaningful change can be brought about via the Labour Party is a difficult and highly controversial topic. The Labour Party has a long history of treachery and imperialism; of doing the bidding of the capitalists under a ‘left’ cloak. It’s perfectly clear that Labour isn’t a vehicle for socialism. However, an important point to consider is that Labour is in a process of change, and, for the first time in many decades, it is moving to the left rather than to the right.

Tens of thousands of new members have joined, the vast majority of them with a view to supporting Corbyn’s platform (it’s estimated that membership has doubled since May’s general election). Corbyn has stated his intention to democratise the party, reducing the decision-making power of the Parliamentary Labour Party and empowering the conference and the constituency branches. He has also said that he’d like to see membership to increase to around half a million (it’s currently around 360,000 and rising fast). At what point does quantity turn into quality? At what point can we say that Labour has become a fundamentally different organisation to the New Labour of Blair and Brown?

Corbyn is in such an unusual position – elected with a huge majority but in a tiny minority of progressive MPs within the Parliamentary Labour Party – that he really has no choice but to grow and strengthen the grassroots membership in order to consolidate his position. Hence the Labour Party has become a crucial arena of class struggle; a place where a political battle is taking place between a pro-neoliberal, pro-imperialist right which has grown accustomed to tightly holding the reins, and a small but growing socialist-oriented left that’s been able to capture the party leadership. This will be one of the key political struggles of our era.

If Corbyn and his team can succeed in fighting off the party bureaucracy and sinister manoevrings of the Blairites, it’s possible we could see a Labour government elected in 2020 with a clear popular mandate to end austerity, stop British participation in imperialist wars, fight against racism and xenophobia, and defend the welfare state. This would be of obvious benefit to the poor of this country; it would also benefit those countries that suffer as a result of British imperialist policy; and it would also provide a boon for other anti-austerity, left-oriented governments and movements in Europe and further afield. Such a development, particularly in a major imperialist centre like Britain, would significantly affect the global balance of forces in a way that is favourable to our side.

Meanwhile, in the years leading up to the next general election, with Corbyn as the leader of the opposition, some room opens up for opposing imperialist and neoliberal policy in a practical way. Although there is a natural tension between a Corbyn-led Labour and the SNP – with Corbyn attempting to win back support in Scotland, and the SNP concerned at his ability to do just that – there is the chance of building a large parliamentary opposition that could disrupt the government’s viciously anti-poor agenda and put obstacles in the way of its military adventures. As Mhairi Black said in her maiden speech to the House of Commons:

“No matter how much I may wish it, the SNP is not the sole opposition to this Government, but nor is the Labour party. It is together with all the parties on these benches that we must form an opposition, and in order to be effective we must oppose not abstain. Let us come together, let us be that opposition, let us be that signpost of a better society. Ultimately people are needing a voice, people are needing help, let’s give them it.”

Is such an opposition worth having? You can answer the question by looking at how much the political establishment doesn’t want it to happen.

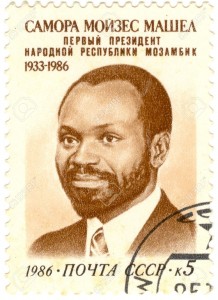

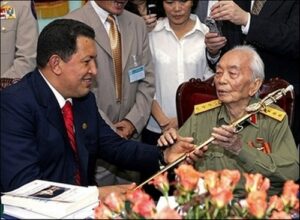

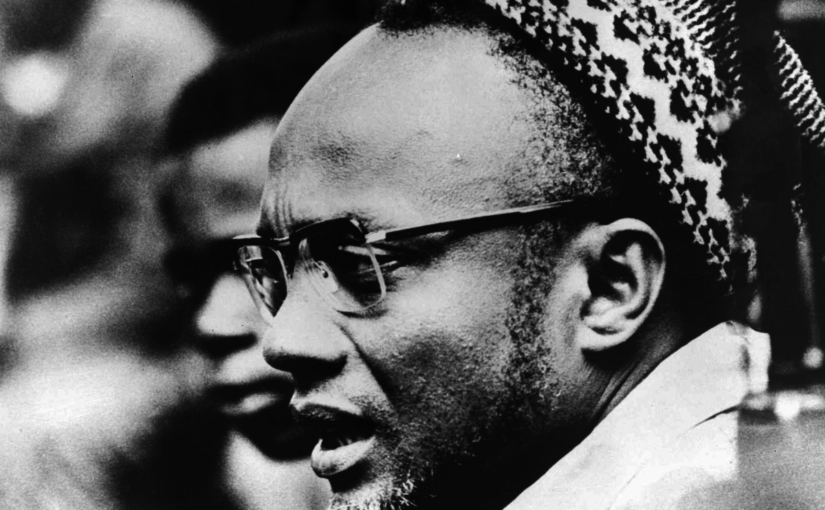

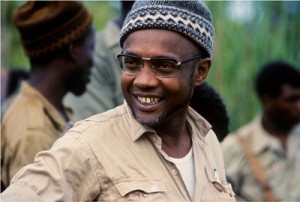

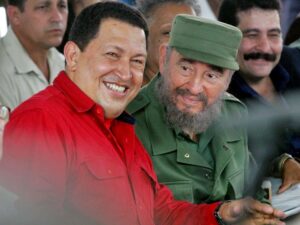

Discussing the potential role of the European working class movement, Samora Machel – pre-eminent leader of the Mozambican Revolution – said: “Progress by the representative movements of the European labouring masses, development in the trends that strive for unity of the progressive forces within capitalist society, are tending to weaken imperialism and so contribute to our common success.” This is a good example of revolutionary pragmatism from someone that doesn’t have the luxury of indulging in consequence-free ultra-left posturing. Socialist and progressive states of the so-called third world understand the value of having relatively progressive people and organisations in positions of power in the imperialist countries. Any brake applied to the most vicious and militaristic imperialism constitutes a tangible boost to the global struggle against imperialism. In the words of Argentina’s ambassador to the UK (and close confidant of Hugo Chávez) Alicia Castro: “Chávez rooted us in the basis of the widest possible unity – unity with anyone with the slightest chance of joining forces against imperialism“.

Discussing the potential role of the European working class movement, Samora Machel – pre-eminent leader of the Mozambican Revolution – said: “Progress by the representative movements of the European labouring masses, development in the trends that strive for unity of the progressive forces within capitalist society, are tending to weaken imperialism and so contribute to our common success.” This is a good example of revolutionary pragmatism from someone that doesn’t have the luxury of indulging in consequence-free ultra-left posturing. Socialist and progressive states of the so-called third world understand the value of having relatively progressive people and organisations in positions of power in the imperialist countries. Any brake applied to the most vicious and militaristic imperialism constitutes a tangible boost to the global struggle against imperialism. In the words of Argentina’s ambassador to the UK (and close confidant of Hugo Chávez) Alicia Castro: “Chávez rooted us in the basis of the widest possible unity – unity with anyone with the slightest chance of joining forces against imperialism“.

It makes sense, then, that Corbyn’s victory in the leadership contest has been greeted with pleasant surprise by such diverse organisations and individuals as the President of Argentina, the Russian ambassador to the UK, Syriza, Sinn Féin, and Podemos leader Pablo Iglesias; or that news outlets such as Telesur, RT, Press TV and Prensa Latina have been largely positive in their coverage. Limitations notwithstanding, the movement around Corbyn presents significant possibilities that we can’t afford to ignore.

Limitations of Corbyn and left Labour

None of this is to say that Corbyn and the movement around him are devoid of weaknesses and limitations; nothing could be further from the truth. Corbyn is not Lenin, or Chávez, or Allende, or indeed Lula. His socialism is old-Labour clause-four socialism, which is not really socialism in any scientific sense of the word, but rather a Keynesian capitalism which seeks to reduce class conflict by somewhat improving the conditions of the oppressed. Historically, this type of ‘socialism’ has, in the imperialist countries, generally been connected with social chauvinism: support for ruling class foreign policy, on the basis that the profits derived from colonialism and neocolonialism provide the economic basis for improved living conditions at home. That is to say: social democracy has a deep-rooted historical connection with imperialist bribery.

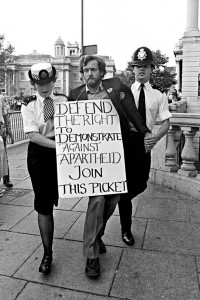

So what to make of Corbyn’s anti-imperialism? It’s good and bad. He has always been a strong supporter of a united Ireland – a key issue for the British left, and something that many get wrong. He is a solid supporter of Palestine, and an admirer of the Cuban and Venezuelan revolutions. He was very active in the campaigns against South African apartheid and the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (a close personal friend of Margaret Thatcher) in Chile.

So what to make of Corbyn’s anti-imperialism? It’s good and bad. He has always been a strong supporter of a united Ireland – a key issue for the British left, and something that many get wrong. He is a solid supporter of Palestine, and an admirer of the Cuban and Venezuelan revolutions. He was very active in the campaigns against South African apartheid and the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (a close personal friend of Margaret Thatcher) in Chile.

On other key issues, his anti-imperialism is overshadowed by a human rights-oriented left liberalism. In a world where China and Russia constitute the undisputed economic and military leadership of the fightback against Nato hegemony, and where all progressive states – from Venezuela to South Africa – are to a greater or lesser extent rallying round that leadership, it’s a shame that Corbyn has nothing positive to say in relation to either China or Russia. Indeed, he is a supporter of the CIA-linked ‘Free Tibet’ campaign – arguably the central plank of the west’s anti-China propaganda strategy.

However, there’s no need to over-emphasise these concerns in relation to Russia and China. On the most important question regarding Russia, Corbyn is actually ahead of much of the left, in terms of understanding the quasi-fascist nature of the Ukrainian regime (“The far-right is now sitting in government in Ukraine. The origins of the Ukrainian far-right go back to those who welcomed the nazi invasion in 1941 and acted as allies of the invaders”) and the predatory imperialist nature of Nato’s eastward expansion. Meanwhile, if nothing else, simple economic pragmatism should help to improve Corbyn’s position on China.

Corbyn opposes Scottish independence. I, like Craig Murray, “am quite sure his opposition is not of the Britnat imperialist variety”, given his lifelong support of Irish republicanism. The simple fact is that it would be political suicide for Corbyn to sign up to Scottish independence at a time when he is pushing Labour in the direction of policies that are supported by a far higher percentage of the Scottish population than the English population. That said, he has stated that Scottish Labour MPs should have a free vote on independence. The key thing for the moment is to build an oppositional consensus against austerity, xenophobia and war, as discussed above.

Of course, if Corbyn is far from fantastic on matters anti-imperialist, it goes without saying that his political party as a whole is a lot worse. Labour is an imperialist party with a horrific record of participation in British colonialism and neocolonialism. It doesn’t stop being imperialist overnight just because its membership have managed to elect a decent human being to the leadership. In playing down the imperialist history of his party, Corbyn creates illusions in that party, focussing on building consensus against austerity rather than around broader anti-imperialism.

But such is the challenge for those that understand the world at a deeper-than-surface level: to find ways to educate and agitate such that a rising progressive sentiment is channelled towards a real, lasting, effective socialist and anti-imperialist movement. The point is to appreciate the value and significance of Corbyn without deifying him or looking to him to provide a grand strategy for overthrowing capitalism and imperialism.

To defend or denounce

“The whole task of the communists is to be able to convince the backward elements, to work among them, and not to fence themselves off from them by artificial and childishly ‘left’ slogans.” (Lenin)

The left in Britain finds itself in a new and entirely unexpected situation; a situation that calls not for dogmatic sloganeering but for a creative application of revolutionary understanding, and an updating of strategies and tactics to take new developments into account.

In Corbyn, we have a decent sort of person who strongly identifies with the oppressed, and whose basic policy base is progressive and worthy of support, even if his party won’t let him implement much of it. What’s more, the people – hundreds of thousands of them – attracted by Corbyn’s policies are exactly the type of people that should be won over to better, more consistent socialist and anti-imperialist politics.

To what extent is it possible to influence, mobilise and educate this constituency? Certainly not all the people inspired by Corbyn are salt-of-the-earth workers or disenfranchised immigrant youth; probably a majority would be considered ‘middle class’, and would in the past have stuck with safe, middle-of-the-road liberal politics. However, as described above, modern capitalism is ‘proletarianising’ vast numbers of people. The impoverishment and concomitant radicalisation of the middle class is not a new phenomenon; indeed it is one of the processes on which the possibility of winning socialism in the imperialist countries is predicated.

Corbyn’s campaign has created a huge wave of enthusiasm among hundreds of thousands of people for whom ‘socialism’ and ‘anti-imperialism’ are not dirty words; who want to defend migrants’ rights; who want to defend free education, healthcare, disability allowances; who do not support British participation in imperialist wars; who hate ‘austerity’ economics; who are willing to fight racism; who want to put preservation of the planet before the creation of profit; who have seen the SNP campaigning on a platform significantly to the left of Labour and who want something similar in England. That all these thousands of people getting on board with the Corbyn campaign haven’t been put off by the media’s hate propaganda indicates that they can’t simply be dismissed as weak-kneed liberals.

Therefore it should be obvious enough that, rather than pouring contempt on these people for their inevitable weaknesses, the thing to do is to understand those weaknesses and seek to overcome them through education and shared experience in class struggle. As the PSL statement quoted above notes: “The British and US rulers are supremely class conscious, and are all too aware that the deep assault against the living standards of the working classes could dynamically awaken a new generation to mass struggle. They are keenly aware that a fire of fightback and resistance once lit can spread outside of their control and be the basis for a revival of revolutionary socialism far outside the limits of social democracy.”

The choice for those to the left of Corbyn is clear: join in with the class enemy in denouncing Corbyn and pouring cold water on the movement building around him; or defend Corbyn, engage with his constituency, and attempt to develop this movement into something of lasting value.

After all, what are the alternatives available in terms of attempting to build a socialist movement in Britain? As it stands, there is no mass movement to the left of Corbyn. There are dozens of small revolutionary organisations, but these are all but invisible to the vast majority of the population. In the painfully backward situation we’re in, with socialist, communist and anti-imperialist forces in disarray, there isn’t anything commendable about leaving parliamentary politics to the Blairs, Camerons and Farages so that they can carry on running their for-us-by-us millionaire governments with impunity.

Does Jeremy Corbyn create illusions in the Labour Party? Well, yes. But this is hardly the most pressing political problem for the left at this moment. And support for Corbyn does not preclude, or get in the way of, or diminish the need for, building a revolutionary alternative. Do we need to re-build an anti-imperialist, socialist, communist movement? Without a doubt! But we can hardly blame Corbyn for the fact that we haven’t managed it thus far.

The ruling class attack on Corbyn and on the ‘left Labour’ project he leads will be vindictive and persistent. The blows will come from all angles – not least from the inevitably ‘inclusive’ shadow cabinet and the right-wing-dominated Parliamentary Labour Party. Corbyn, John McDonnell, Diane Abbott and others are being, and will continue to be, subjected to the wrath and ridicule of the press. The class enemy will not rest until Labour is back in ‘safe hands’ and the movement against neoliberalism and war fizzles out.

It is critical that we disrupt this agenda; that we defend Corbyn, his limitations notwithstanding; that we explore ways to push forward this growing movement and political consciousness. Time to defend what has been gained, and work out how to build on it.