Jenny Clegg’s book China’s Global Strategy, published by Pluto Press in 2009, is an extremely useful examination of China’s economic and political outlook. It focuses on the country’s overriding strategy of developing a ‘multipolar world’, where no one country dominates and where the countries of Asia, Africa and Latin America – for centuries ground down by colonialism and neo-colonialism – have space to develop in peace.

China’s vision: survival and peaceful development in a hostile world

China’s strategy is derived from one simple overriding aim: the survival of People’s China. The need to maintain China’s sovereignty in the face of intense imperialist hostility gives rise to the main aspects of China’s economic and geopolitical strategy: integrating itself into the world economy; opposing US domination; promoting ‘balance’ – a larger (and increasing) number of influential powers; promoting South-South cooperation; utilising the rivalry between the different imperialist powers to push forward the development agenda; and promoting the general rise of the third world.

All these elements can be summed up as the drive towards a multipolar world; a world involving “a pattern of multiple centres of power, all with a certain capacity to influence world affairs, shaping a negotiated order“.

The theory of multipolarity is largely the product of the collapse of the USSR and the boost it gave to the hegemonic ambitions of the United States. Despite the long period of hostility between China and the USSR, the latter’s existence was a powerful force of balance in world politics. With the USSR gone, the US embarked with renewed energy on an orgy of neocolonial domination: extending the reach of NATO further and further eastwards; waging wars against Iraq, Afghanistan, Yugoslavia and Libya in the pursuit of natural resources and geopolitical advantage; imposing structural adjustment programmes on dozens of third-world countries; and deepening its military dominance through ‘missile defence’ and the like.

Clegg notes that “China … was left more exposed to US hegemonism by the collapse of the USSR and the eastern European communist states. The West had attempted to isolate China, imposing sanctions following the Tiananmen crackdown in 1989 …” (pp54-55)

“Capitalising on advantages in technical innovation, especially in hi-tech weaponry, as well as its cultural influence, the United States was re-establishing its power superiority. By reviving both NATO and its military alliance with Japan, the United States was able to reincorporate Europe and Japan as junior partners and rein in their growing assertiveness, and to contain Russia as well as China, so weakening the multipolar trend …

“For Chinese analysts [the war against Yugoslavia] marked a new phase of US neo-imperialist interventionism and expansionism – a bid to create a new empire – which presaged new rounds of aggression and which would be seriously damaging for the sovereignty and developmental interests of many countries. The United States was stepping up its global strategic deployment, preparing to ‘contain, besiege and even launch pre-emptive military strikes against any country which dares to defy its world hegemony’.” (p59; citation from Wang Jincun, ‘”Democracy” veils hegemony’)

Clegg cites [former Chinese President] Hu Jintao at a meeting of senior Communist Party leaders in 2003: “They [the US] have extended outposts and placed pressure points on us from the east, south and west. This makes a great change in our geopolitical environment.” (p34)

In this dangerous environment, faced with the unrelenting hostility of the world’s only remaining superpower, China developed the clever – albeit dangerous – strategy of integrating itself into the world economy and, in so doing, making itself indispensable to the US. It is clear that this policy has, so far, been successful in its main objective; although the US is desperate to slow China’s economic growth and restrict its political influence, it finds itself unable to launch the type of diplomatic (or indeed military) attack it would like to, for fear of Chinese economic retaliation.

As Clegg puts it: “China is using globalisation to make itself indispensable to the functioning of the world economy, promoting an interdependence which means it becomes increasingly difficult for the United States to impose a strategy of ‘isolation and encirclement’.“

Indeed, Clegg suggests that, “at its core, China’s is a Leninist strategy whose cautious implementation is infused with the principles of protracted people’s war: not overstepping the material limitations, but within those limits ‘striving for victory’; being prepared to relinquish ground when necessary and not making the holding of any one position the main objective, focusing instead on weakening the opposing force; advancing in a roundabout way; using ‘tit for tat’ and ‘engaging in no battle you are not sure of winning’ in order to ‘subdue the hostile elements without fighting’.” (p223)

Manoeuvring towards multipolarity

Twenty-one years after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the conditions are certainly right for a multipolar world, and this is beginning to take shape.

That the various major countries no longer unquestioningly accept US dominance is demonstrated by the bitterness over the Iraq war, which was opposed by France, Germany, Russia and India. More recently, Russia and China have used their position on the UN Security Council to prevent a full-scale military assault on Syria. Meanwhile, a strong anti-imperialist trend has been emerging in Latin America, with Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, Ecuador and Nicaragua leading the move away from US dominance. Southern Africa – not so long ago dominated by vicious apartheid regimes in South Africa, South West Africa (Namibia) and Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and by Portuguese colonialism in Angola and Mozambique – is now largely composed of progressive states.

The major ‘non-aligned’ powers such as Brazil, Russia, South Africa, India and Iran are all forging closer relations with China and are starting to take a leading role in developing a new type of world – a ‘fair globalisation’, as the Chinese put it.

China has focused strongly on building international alliances at every level. It initiated the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), which was constituted in 2001 in order to cooperate with regional allies on issues such as energy strategy, poverty alleviation and combating US-sponsored separatism. The SCO was built around the Sino-Russian strategic partnership, but includes a number of former Soviet republics in Central Asia as full members, while a number of key Asian powers, such as Iran, India and Pakistan, presently have observer status and may become full members in the future.

China is one of the driving forces behind BRICS – the international alliance of the five major emerging economies: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. BRICS is firmly focused on promoting South-South cooperation, and the BRICS development bank (which could be launched within two years) will be provide crucial investment for development projects in Africa, Asia, South America and the Caribbean.

China is also starting to lead east Asian economic cooperation, proposing and implementing the China-ASEAN Free Trade Agreement (ACFTA), under which the weaker east Asian economies are given priority access to China’s markets, while China also benefits from the technical and other advantages of the more developed economies of the region.

“Far from cutting the ground beneath the export-oriented countries of East Asia, the development of manufacturing in China has been the engine of regional economic growth. After 2001, with the United States in recession and the Japanese economy still stagnating, China’s growth was key to reflating the regional economy still shaky after the 1997 crisis.” (p116)

Through its policies of regional security and economic cooperation, as well as its complex relationship with the various imperialist powers, China is frustrating US expansionism. “The US aim to encircle China though networking the hub-and-spokes pattern of its bilateral military alliances into an Asian NATO based on the conditions of its own absolute security, is therefore being thwarted as China, region by region, seeks to foster an alternative model of cooperative security.” (p121)

But hasn’t China capitulated to the US?

Clegg notes, and treats seriously, the left critique of China: that it is going down the path towards capitalism; that it is following the path of Gorbachev and the Soviet Union.

She writes: “Across a wide spectrum of view among the western Left, China’s gradual path of economic reform since the later 1970s has been regarded as a ‘creeping privatisation’ undermining self-reliance bit by bit with foreign investment steadily encroaching on the country’s economic sovereignty. Its 2001 WTO accession is thus seen as the outcome of a gradual process of capitalist restoration – a final step in sweeping away the last obstacle in the way of China’s transition from socialism.“

Clegg argues that, on the contrary, China’s “’embrace of globalisation’ is in fact a rather audacious move to strengthen its own national security … The goal is not to transform the entire system into a capitalist one but to improve and strengthen the socialist system and develop the Chinese economy as quickly as possible within the framework of socialism.” (p124)

This is the basis on which China joined the WTO – in order to able to “insert itself into the global production chains linking East Asia to the US and other markets, thus making itself indispensable as a production base for the world economy. This would make it far more difficult for the United States to impose a new Cold War isolation.“

Further, China’s integration in the world economy has allowed it to be a part of “the unprecedented global technological revolution, offering a short cut for the country to accelerate its industrial transformation and upgrade its economic structure. By using new information technologies to propel industrialisation, incorporating IT into the restructuring of SOEs [state-owned enterprises], China would be able to make a leap in development, at the same time using new technologies to increase the state’s capacity to control the economy.” (pp128-9)

Clegg quotes Rong Ying’s explanation of the economic drivers behind China’s strategy: “Developing countries could make full use of international markets, technologies, capital and management experience of developed countries to cut the cost of learning and leap forward by transcending the limits of their domestic markets and primitive accumulation.” (p84; Rong Ying is a foreign affairs expert at the China Institute of International Studies)

In the author’s view, China is not abandoning Leninism by seeking to engage with the US; rather, it is following the creative and pragmatic spirit of Leninism, making difficult compromises in a novel and extremely tough situation. Moreover, in dealing with second-rate imperialist powers, such as France and Germany, for example, Chinese strategists have taken to heart Lenin’s advice to take “advantage of every, even the smallest, opportunity of gaining an … ally, even though this ally be temporary, vacillating, unreliable and conditional“. (Cited on p99)

Despite the apparent similarities between China’s ‘reform and opening up’ and the revisionist era in the Soviet Union, there are also some important differences.

First, of course, the prevailing economic and political circumstances: China in 1980 was significantly less developed than the USSR in 1960; the peasant population was (and is) still much larger than the working class; the average standard of living was far behind the major capitalist countries, as was the level of technical development.

Second, the imperialist countries had made huge advances in military technology, which China had to catch up with if it wanted security. Therefore, the Chinese invocation of Lenin’s New Economic Policy (the economic policy introduced in the Soviet Union in 1921 that introduced market elements in order to kick-start the economy after the war of intervention) has a lot more substance than Gorbachev’s.

Naturally, having seen what happened in the USSR, people get anxious when they see market reforms in China. However, if the “proof of the pudding is in the eating”, then it should be noted that, whereas the USSR stagnated through the 1980s, China has witnessed the most impressive programme of poverty alleviation in human history .

Whereas, in the last years of the USSR’s existence, the needs of its population were increasingly ignored, in China, the needs of the people are very much at the top of the agenda. Whereas, in the USSR, technical development fell way behind the imperialist countries in the 80s, in China, it is rising to the level of the imperialist countries. Indeed, the centre of gravity of the scientific world is slowly but surely shifting east. And China is playing a valuable role in sharing technology, for example by launching satellites for Venezuela, Ecuador, Nicaragua and Bolivia.

Whereas, in the USSR, the ruling party (the Communist Party of the Soviet Union) started to lose a lot of its prestige, the Chinese Communist Party remains extremely popular and is by far the largest political party in the world, with over 85 million members. And the Chinese leadership have clearly studied and understood the process of degeneration in the USSR. The new President, Xi Jinping, has talked about this issue a number of times, and warned that the party must remain firm in its principles and its working class orientation. A recent article quotes Xi telling party insiders that “China must still heed the ‘deeply profound’ lessons of the former Soviet Union, where political rot, ideological heresy and military disloyalty brought down the governing party. ‘Why did the Soviet Union disintegrate? Why did the Soviet Communist Party collapse? An important reason was that their ideals and convictions wavered’, Mr Xi said. ‘Finally, all it took was one quiet word from Gorbachev to declare the dissolution of the Soviet Communist Party, and a great party was gone'”.

So perhaps what we are seeing is an extremely complex, creative, dialectical and dynamic approach to developing the aims of Chinese socialism and global development. After all, to refuse to accept any compromise; to demand revolutionary ‘purity’ at the expense of the practical needs of the revolution; would be utterly un-Marxist.

Is China the latest imperialist country?

Another accusation that is often levelled against China (usually by liberal apologists of imperialism) is that it has become an imperialist country; that its investment in dozens of third world countries amounts to a policy of ‘export of capital’; that it has established an exploitative relationship with those countries with which it trades.

To be honest, it’s difficult to take these claims seriously. By and large, they are the jealous cries of British, US, Japanese, French and German finance capitalists, who have got enormously rich out of the structural adjustment programmes imposed on so many third world countries in the 1990s and whose profits are now threatened by China’s emergence as an alternative source of development capital in Asia, Africa and South America.

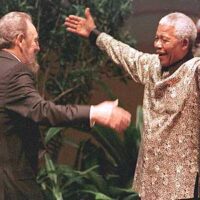

Those countries of the Global South that are working hard to improve the lives of their populations are deeply appreciative of the support they get in this regard. Venezuela’s rise over the last 14 years would have been extremely difficult without Chinese support, and the much-missed Hugo Chávez was a great friend of China. Chinese investment is also very important to Cuba, South Africa, Bolivia, Zimbabwe, Ethiopia, Jamaica and elsewhere. An important recent example is the 40-billion-dollar deal whereby China will build in Nicaragua an alternative to the Panama Canal – “a step that looks set to have profound geopolitical ramifications“. As Clegg writes: “China’s large-scale investment and trade deals are starting to break the stranglehold of international capital over the developing world.” (p212)

Since joining the WTO, “China’s lower tariffs and rising imports have helped boost trade with other developing countries, many of which are experiencing significant trade balances in their favour for the first time in decades … Thanks to increased demand from China, the value of exports by all developing countries rose by 25 percent, bringing their share in world trade to 31 percent in 2004, the highest since 1950.

“Since 2004, China has also taken major steps in its commitment to cooperation through large-scale investment in the developing world. From Latin America to Africa, countries are increasingly looking to China as a source of investment and a future business partner, as China seeks synergies in South-South cooperation…

“By funding infrastructure projects in other developing countries China is helping to boost trade so that they can lift themselves out of poverty. In addition, China has reduced or cancelled debts owed by 44 developing countries and has provided assistance to more than 110 countries for 2,000 projects.” (p210)

Further: “Over 30 African countries have benefited from China’s debt cancellations to the tune of $1.3bn … Investment credit is to be doubled to $3bn by 2009 [it is now more than double this figure]. Chinese companies offer technical assistance and build highways and bridges, sports stadiums, schools and hospitals to ensure projects deliver clear benefits to locals, for example in helping to restore Angola’s war-ravaged infrastructure.” (p211)

China is intent on assisting its brothers and sisters in the third world, and it feels that, by improving south-south cooperation, by sharing its technical know-how, and by helping to raise developing countries out of poverty, it is moving towards its overall strategy of multipolarisation.

Clegg sums up China’s international policy as attempting to create “a new international order based on non-intervention and peaceful coexistence without arms races, in which all countries have an equal voice in shaping a more balanced globalisation geared to the human needs of peace, development and sustainability“. (p226)

A dangerous game

China has followed a path of rapid growth, which has led to phenomenal results in terms of improving the lives of ordinary people. In the last 30 years, the proportion of Chinese people living below the poverty line has fallen from 85% to under 16%. Life expectancy is 74 (a rise of 28 in the last half-century!). Literacy is an impressive 93%, which compares extremely well with the pre-revolution level of 20% (and, for example, with India’s 74%).

Nonetheless, the economic reforms have undoubtedly brought serious problems – in particular: unemployment (albeit a reasonably manageable 4%), a massive increase in wealth disparity, regional disparities, an unsustainable imbalance between town and country, reliance on exports, the growth of unregulated cheap labour, and an unstable ‘floating population’ of rural migrants.

These are, of course, problems that face many other countries as well, including the wealthy imperialist ones. The difference is that in China there are both the political will and the economic resources to seriously address these issues. Huge campaigns are under way to reduce unemployment, to reduce the gap between town and country, to modernise the rural areas, to create employment, to wipe out corruption, to empower the grassroots, to improve workplace democracy, to improve access to education, to improve rural healthcare, and so on. Such are the issues on which the government’s attention is firmly focused.

“The problems in the rural healthcare and education systems have been placed centre stage in the government’s ‘people first’ agenda. In 2006, a rural cooperative medicare system was started in low-income areas, with farmers, central and local government all making equal contributions. According to government estimates, the new scheme already covers 83 percent of the rural population, and the aim is for complete coverage of the whole population by 2010 … To improve the situation in rural education, the government is abolishing fees for all 150 million rural students in primary and secondary education, while increasing support for teacher training.” (p155)

China is also strongly focused on empowering its trade unions to represent the interests of the working class in its bid for better pay and conditions. Unlike in Britain, corporate no-union policies are illegal, and union officials have the right to enter the premises of non-union enterprises in order to recruit.

Clegg notes that “the rabidly anti-union Wal-Mart was compelled by law to recognise a trade union for the first time anywhere in the world in one of its outlets in Fujian province in 2006“. (p162)

Conclusion

There are a variety of opinions with regard to the political and economic path that China is following. Only time will tell if the Chinese vision will lead to the long-term strengthening of socialism and a more equitable world. As things stand, this seems to be what is happening, and that is one of the reasons that the outlook for the world is much more favourable than it was at the time of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Progressive people worldwide should take courage in China’s achievements, its people-centred policy, its continued support for the developing world, and its leadership role within the progressive family of nations. The destruction of People’s China would be a tragedy for the people of China and the developing world, and would be a disastrous setback for the international socialist and anti-imperialist movement. For that reason, China should be defended and supported.

China’s Global Strategy gives a thorough overview of the current political and economic thinking in China, and is the first book in the English language to perform this task in such a succinct way. While Clegg is essentially supportive of China’s policy, she certainly does not attempt to sweep its problems under the carpet, and, indeed, deals with those issues at some length. Although the book is written in a relatively academic style, it is nonetheless perfectly readable even for those with little knowledge of Chinese politics, and is an invaluable resource for those wanting to understand the most significant force for progress and peace in the world today.