The recent high-profile summit of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC), held in Beijing at the beginning of September, has inspired some familiar accusations in the North American and West European press: China is the new colonial power in Africa; China is attempting to dominate African land and resources; Africa is becoming entangled in a Beijing-devised debt trap; Chinese investment in Africa only benefits China; and so on.

This article addresses these accusations and concludes that they are based on shaky foundations; that China is by no means an imperialist power; that increasing Africa-China relations are of significant benefit to the people of Africa; that Chinese assistance and investment could well be the key factor in breaking the cycle of underdevelopment and poverty in Africa.

What is imperialism?

If we’re going to understand whether or not China is imperialist, it’s a good idea to agree what imperialism is, since the word suffers from fairly widespread misinterpretation. Based on the characteristics of imperialism outlined in Lenin’s classic study, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, many conclude that China is an imperialist country. After all, it has several enormous companies that could reasonably be described as monopolies; it has a handful of very large (state-owned) banks that have significant influence on investment; and it’s increasingly engaged in the ‘export of capital’, investing in business operations around the world.

However, it should be obvious enough that no definition of the word imperialism is useful if it doesn’t include the concept of domination. The word derives from the Latin imperium, meaning supreme authority, or empire. There is no imperialism without empire. Which is not to say that imperialism no longer exists now that the colonial era is (for the most part) finished; it’s perfectly possible to maintain a de facto empire, for example through participating in the domination of another country’s markets.

A reasonable, concise definition of imperialism is put forward by the political analyst Stephen Gowans: “imperialism is a process of domination guided by economic interests.”1 This process of domination can be characterised as “the activity, enterprise and methodology of building empires”. However, empires “can be declared and formal, or undeclared and informal, or both. Whatever form they take, empires are structures predicated on systems of domination, of one country or nation over another.” For example, the US has few actual colonies, but it unquestionably uses its enormous economic and political muscle to dominate other countries, with a view to creating conditions for its own capitalist class to more rapidly expand its capital.

The recently-deceased Egyptian economist Samir Amin describes how “the countries in the dominant capitalist centre” – by which he means the US, Europe and Japan – leverage “technological development, access to natural resources, the global financial system, dissemination of information, and weapons of mass destruction” in order to dominate the planet and prevent the emergence of any state or movement that could impede this domination. The vast accumulation of capital in the imperialist heartlands has its counterpart in a ‘lumpen-development’ in much of the rest of the world – “a dizzying growth of subsistence activities, called the informal sphere — otherwise called the pauperisation associated with the unilateral logic of accumulation of capital.”2

The US goes to considerable lengths to build a global economic order that suits its own interests, and in so doing it actively diminishes the sovereignty of other countries. The most extreme – but sadly not uncommon – example of this is imperialist war: using military means to secure economic and political outcomes, such as we have seen recently in Libya, Iraq, Afghanistan and Yugoslavia.

We can perhaps then condense the idea of imperialism down to a fundamentally unequal relationship between countries (or blocs of countries) at differing levels of development, with the more developed countries using their military and financial power to produce outcomes that favour themselves and harm the less developed countries.

If we can prove that China is involved in this type of activity – that it seeks to dominate foreign markets and resources, that it uses its growing economic strength to affect political decisions in poorer countries, that it engages in wars (overt or covert) to secure its own interests – it would then be reasonable to conclude that China is indeed an imperialist country and that its engagement with Africa is an example of imperialism.

What imperialism in Africa looks like

At this point we’ll take a brief look at what imperialism in Africa has looked like in the past. Perhaps, in so doing, we’ll stumble upon some characteristics that can also be found in China’s relationship with Africa today.

In his classic 1972 study How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, the Guyanese activist-scholar Walter Rodney catalogues Europe’s relationship with Africa from the early days of the transatlantic slave trade through to the post-colonial era. The story that emerges is one of systematic plunder and an active underdevelopment that helped to furnish European development.

Rodney notes that, in the 16th century, several areas of Africa were on a path of technical progress similar to, albeit slightly behind, Western Europe: “Several historians of Africa have pointed out that after surveying the developed areas of the continent in the 15th century and those within Europe at the same date, the difference between the two was in no way to Africa’s discredit. Indeed, the first Europeans to reach West and East Africa by sea were the ones who indicated that in most respects African development was comparable to that which they knew.”3

However, the European powers were able to use certain advances – most notably in the areas of shipbuilding and weapons manufacture – to establish a profoundly unequal trade relationship with Africa. This, along with the need to find a capable labour force for the new American colonies, laid the ground for the transatlantic slave trade, which is estimated to have denuded the African continent of up to half its population. Rodney poses the question: “What would have been Britain’s level of development had millions of its people been put to work as slaves outside of their homeland over a period of four centuries?”

The conversion of Africa into a resource pool for European capital was a powerful engine of European capitalist growth in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. As Marx famously wrote, “the discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of black skins, signalled the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production.”4

The colonial occupation of Africa, which lasted from the 1880s until the wave of liberation in the second half of the 20th century, served to significantly deepen the economic subjugation of the continent. Enforced by a fascistic military repression – most notoriously in the Belgian colony of Congo, where natives’ failure to meet the rubber collection quota was punishable by death – European colonialism allowed for the most extravagant exploitation of African labour and natural resources, whilst offering practically nothing in terms of economic progress for the local population.

Empire apologists in Britain, France and Portugal occasionally insinuate a ‘good side’ onto their erstwhile empires – after all, were railways and schools not built? Yet the sum total of these things (which anyway were built specifically to meet the needs of the colonial masters) is vanishingly small – so much so that, “the figures at the end of the first decade of African independence in spheres such as health, housing and education are often several times higher than the figures inherited by the newly independent governments”. As Rodney observes, “it would be an act of the most brazen fraud to weigh the paltry social amenities provided during the colonial epoch against the exploitation, and to arrive at the conclusion that the good outweighed the bad.”

European colonialism contributed nothing to the technological or institutional development of Africa, because this would have created competition for European capitalism and impeded the far more important task of draining maximum possible wealth from the continent.

But imperialism in Africa is not just a thing of the past; it didn’t end with the independence of the former colonies. As Samir Amin writes: “The dominant capitalist centres do not seek to extend their political power through imperial conquest because they can, in fact, exercise their domination through economic means.”5 Since the 1980s, the principal mechanism of imperialist domination in Africa has been economic blackmail: international credit agencies obliging governments to sign up to harmful economic strategies. The most notorious (and typical) example of this is the Structural Adjustment Program (SAP); SAPs are loans from the IMF and World Bank, typically taken out in a crisis situation (in response to a drought, for example), and disbursed on the condition that the recipient country implement a packet of ‘neoliberal’ reforms – privatising key industries and resources, opening up markets to international competition, and liberalising prices.

The SAPs have been a disaster for Africa. Scarce resources such as water have been taken out of the public domain and placed in the hands of globalised privateers. Nascent industries, previously protected by governments trying to develop home-grown manufacturing, have been decimated, dreams of development dashed, and vast regions returned to a prostrate position in the global economy, supplying unimproved raw materials to a market they have no meaningful influence over.

This is imperialism, by any reasonable definition. Advanced western countries, often ganging up in order to achieve their aims vis-a-vis the poorer countries, force nominally independent states to undertake economic measures that are specifically designed to benefit those same advanced western countries. In the modern era, this is precisely what the underdeveloping of Africa looks like. And the results speak for themselves: “after nearly thirty years of using ‘better’ (that is, free-market) policies, Africa’s per capita income is basically at the same level as it was in 1980.”6

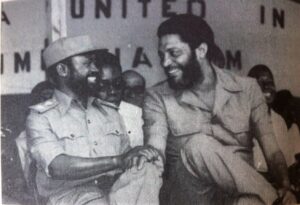

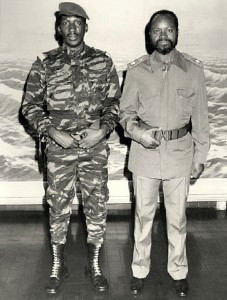

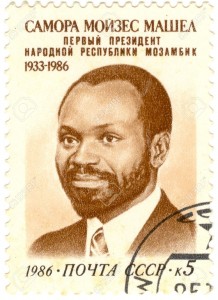

Mozambican independence leader Samora Machel, president from 1975 until his death (almost certainly at the hands of the apartheid South African security services) in 1986, spoke bitterly about the imperialist countries’ visions for post-colonial Africa: “They need Africa to have no industry, so that it will continue to provide raw materials. Not to have a steel industry. Since this would be a luxury for the African. They need Africa not to have dams, bridges, textile mills for clothing. A factory for shoes? No, the African doesn’t deserve it. No, that’s not for the Africans.”7

Various well-paid academics assert that western imperialism is a thing of the past, that Europe and North America have changed their ways, and that Africa is now treated as an equal. While it is palpably false that western imperialism is a thing of the past (is it not imperialism when Nato launches a war on Libya, plunging it into a state of chaos and desperate poverty, in order to remove a government that had consistently refused to adhere to the economic and political ‘rules’?), it’s true that Europe and North America are less reliant on the exploitation of Africa than they once were. This demonstrates only that imperialism can’t be separated from its historical context. Western Europe, North America and Japan have reached a level of productivity and technological advance such that outright plunder of other nations constitutes only a relatively small part of their economic activity; however, they reached this point to a significant degree owing to their ruthless oppression of less developed countries. Thus the designation of a given country as ‘imperialist’ necessarily includes a historical component.

Regardless of these subtleties, Euro-American imperialism maintains an active foothold in Africa today, via a combination of economic blackmail, political manoeuvring, military intervention, and military mobilisation.

A brief timeline of China’s engagement with Africa

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the Chinese leadership moved quickly to create bonds of solidarity between China and the African liberation movements. China was a leading supporter of the Algerian war of liberation and an early supporter of the South African struggle against white minority rule. Nelson Mandela recounts in Long Walk to Freedom that he encouraged Walter Sisulu, then secretary-general of the African National Congress, to visit China in 1953 in order to “discuss with the Chinese the possibility of supplying us with weapons for the armed struggle.”8 The links made during this trip laid the ground for the establishment in the early 1960s of a Chinese military training programme for the newly-founded uMkhonto we Sizwe – the ANC’s armed wing. (An interesting aside: two currently serving African heads of state received military training in China in the 1960s: Eritrean president Isaias Afwerki, and Zimbabwean president Emmerson Mnangagwa.)

Chinese premier Zhou Enlai conducted a landmark tour of ten African nations between December 1963 and January 1964, during which he consolidated China’s anti-imperialist connection with some of the leading post-colonial African states. A few years later, China provided the financing and knowhow for the construction of the Tanzam Railway, which runs 1,860km from Dar es Salaam, the then Tanzanian capital and seaport, to central Zambia. Built with the primary purposes of fomenting economic development and helping Zambia to break its economic dependence on the apartheid states of Rhodesia and South Africa, the Tanzam has been described as “the first infrastructure project conceived on a pan-African scale”.9 It remains an enduring symbol of China’s friendship with independent Africa.

Well into the 1980s, dozens of large state farms were built in Africa as part of the Chinese aid programme – in Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Mali, Congo Brazzaville, Guinea and elsewhere. The US scholar Deborah Brautigam notes that, however, “during the 1970s and 1980s, the Chinese aid program shifted to emphasise much smaller demonstration farms, working with local farmers to teach rice farming and vegetable cultivation.”10

In the 1980s and 90s, partly reflecting shifting political priorities in China and partly in response to data indicating that many of the aid-constructed projects were no longer working very well (if at all), China started to put its engagement with Africa on a more commercial footing, focusing on mutually beneficial deals and joint ventures. China has since become Africa’s largest trading partner, with a total trade volume of $170 billion in 201711, well ahead of the US-Africa figure of $55 billion.12

In addition to trade, China also provides vast low-cost loans for infrastructure projects, with nearly $100 billion loaned to African states by Chinese state-owned banks between 2000 and 2015. A recent article in the Guardian notes that “some 40% of the Chinese loans paid for power projects, and another 30% went on modernising transport infrastructure. The loans were at comparatively low interest rates and with long repayment periods.” The article continues: “Chinese infrastructure projects stretch all the way to Angola and Nigeria, with ports planned along the coast from Dakar to Libreville and Lagos. Beijing has also signalled its support for the African Union’s proposal of a pan-African high-speed rail network.”13

Development, not underdevelopment

“We should jointly support Africa’s pursuit of stronger growth, accelerated integration and industrialisation, and help Africa become a new growth pole in the world economy.” (Xi Jinping)14

The most important point regarding China’s engagement with Africa is that it stimulates development rather than underdevelopment. In that crucial sense, it is profoundly different from the relationship that the US and the major European powers have had with Africa. China’s aid and investment packages promote host countries’ modernisation, technical knowhow and infrastructure. As it stands, manufacturing constitutes only 10 percent of value added in Africa. “Ghana sends cocoa beans to Switzerland, for instance, then imports chocolates. Angola exports crude oil and imports nearly 80 percent of its refined fuel.”15 This is an unsustainable situation that keeps Africa in a subservient position. Industrialisation is the indispensable next step, and this relies on infrastructure, technology and knowledge transfer.

As an aside: even if China’s ambitions were essentially predatory, its presence as an alternative source of investment is beneficial for African economies. Ha-joon Chang notes that, in the 1990s, China became a “major lender and investor in some African countries, giving the latter some leverage in negotiating with the Bretton Woods institutions and the traditional aid donors, such as the US and the European countries”.16

Beyond that, Chinese investment has made possible a fast-expanding infrastructure network that will underpin African economic development for generations to come. This includes railways, schools, hospitals, roads, ports, factories and airports, along with “new tarmac roads linking major regional hubs, including the various townships with proper connection to large cities”.17 By contrast, precious little US/British investment in Africa goes towards infrastructure.

In 2017, China funded over 6,200km of railway and over 5,000km of roads in Africa.18 Thanks in no small part to Chinese finance and expertise, Ethiopia last year celebrated the opening of the first metro train system in sub-Saharan Africa,19 along with Africa’s first fully electrified cross-border railway line, the Ethiopia-Djibouti electric railway.20

Lack of electrification is a major problem for most African countries. According to Deborah Brautigam, “the Latin American supply of electricity is 50 times higher, per rural worker, than sub-Saharan Africa’s”.21 Over 600 million people across the continent have no reliable access to electricity. Many of the biggest Chinese investment projects in Africa are focused on power generation – indeed, 40% of all Chinese loans to Africa last year went towards power generation and transmission.22 The bulk of this energy investment is in hydropower and other renewal technologies.23 For example, China’s Eximbank is providing 85% of the financing for Nigeria’s Mambila hydroelectric power project,24 which will constitute the country’s largest power plant, helping to get electricity to the approximately 40 percent of Nigerians that don’t currently have access.25 It was announced a few months ago that China Eximbank would also provide the bulk of the $1.5 billion funding for Zimbabwe’s largest ever power development project.26

Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, Nigeria’s finance minister from 2003 to 2006 and from 2011 to 2015, notes that “China worked with us to get a balanced package of assistance that has helped build the light rail system in Abuja and four new airport terminals in Lagos, Port Harcourt, Kano and Abuja, among other projects.”27 She reflects on the possibilities for extensive cooperation between Africa and China in the realm of sustainable development: “Together, China and Africa make up one third of the world’s population. Increasing ties between the two could have a vast positive impact for the world’s economy and climate. China’s experiences and expertise should go a long way in helping African countries develop their renewable resources.“

Do Chinese state banks make these investments for purely altruistic reasons? They do not. “China is poor in natural resources, the notable exception being rare minerals, and as a consequence has no choice but to look abroad. Africa, on the other hand, is extremely richly endowed with raw materials, and recent discoveries of oil and natural gas have only added to this.”28 Deals are negotiated on a case-by-case basis with the two sides as equal partners. The whole arrangement has nothing in common with the west’s historic relationship with Africa. As the Zambian economist Dambisa Moyo writes, “the motivation for the host countries is not complicated: they need infrastructure, and they need to finance projects that can unlock economic growth… This is the genius of the China strategy: every country gets what it wants… China, of course, gains access to commodities, but host countries get the loans to finance infrastructure developmental programs in their economies, they get to trade (creating incomes for their domestic citizenry), and they get investments that can support much-needed job creation.”29

Many African countries are already benefiting greatly from their relations with China. As Martin Jacques puts it: “China’s impact on Africa has so far been overwhelmingly positive. Indeed, it is worth asking the question as to where Africa would be without Chinese involvement… China’s involvement has had the effect of boosting the strategic importance of Africa in the world economy.”

China is ploughing resources into educational cooperation with African countries, recently surpassing the US and UK to become the number one destination for anglophone African students (and second most popular destination overall, after France) – a dramatic increase that is explained in large part by “the Chinese government’s targeted focus on African human resource and education development”.30 In his speech to the recent FOCAC summit, Xi Jinping said China will “provide Africa with 50,000 government scholarships and 50,000 training opportunities” in the next three years.31 Even for students without scholarships, China is a popular destination for African students, because its tertiary education system is more affordable than the west’s, and is increasingly of comparable quality and prestige.

China also provides substantial medical aid to Africa, spending an estimated $150 million annually on malaria treatment, crisis response, medicine provision, and support for building hospitals and pharmaceutical factories. In response to the Ebola crisis in 2014, “China dispatched more than 1,000 medical professionals to West Africa, providing 750 million RMB ($120 million) in aid.”32

Non-interference

China has received no shortage of criticism owing to its willingness to work with states such as Zimbabwe and Sudan, which are subjected to boycotts and sanctions by the US-led ‘international community’. Such criticisms are hypocritical and vacuous. China has a long-standing position of non-interference in the political affairs of other countries. As far back as 1955, then-Premier Zhou Enlai sketched the Chinese vision of peaceful and cooperative development at the historic Afro–Asian Conference in Bandung: “By following the principles of mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity, non-aggression, non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, equality and mutual benefit, the peaceful coexistence of countries with different social systems can be realised.”33

Such a position is quite obviously superior to the US/European system of active interference – ie imperialism. China doesn’t participate in or sponsor wars in Africa; it doesn’t engineer coups, subvert elections or finance political campaigns. China has committed no massacres in Africa, nor does it control any private armies. China has no record of assassinating African leaders, encouraging separatist movements, or creating political instability. It doesn’t maintain lobbyists or advisers whose job is to pressure African politicians. China has not demanded ‘structural adjustment’ in any of the countries it invests in; no privatisation, no deregulation, no demands for hollowing out government. China doesn’t use coercion or blackmail. It bids for contracts, and often wins them, mainly because its prices are fair, its costs low, and its quality of work high. In summary, “China appears wholly uninterested in assuming sovereign responsibility and particularly in shaping h social and political infrastructure of host nations”.34

At the recent FOCAC summit, Xi Jinping summed up the Chinese approach to engagement with Africa as follows: “The Chinese people respect Africa, love Africa and support Africa. We follow a ‘five-no’ approach in our relations with Africa: no interference in African countries’ pursuit of development paths that fit their national conditions; no interference in African countries’ internal affairs; no imposition of our will on African countries; no attachment of political strings to assistance to Africa; and no seeking of selfish political gains in investment and financing cooperation with Africa.”

The “five-no” approach is an explicit rejection of imperialist strategy. Rather than criticise China for its policy of non-intervention, it would be much better if other countries could follow its example.

Some common criticisms

Chinese companies only employ Chinese workers

An oft-repeated criticism of Chinese economic activity in Africa is that Chinese companies only employ Chinese workers. This is simply not true. In fact, China creates more jobs in Africa than any other investor.35 Deborah Brautigam, one of the few western China experts to base their work on actual data, writes that “surveys of employment on Chinese projects in Africa repeatedly find that three-quarters or more of the workers are, in fact, local.”36 This is consistent with the findings of Giles Mohan, whose team undertook extensive on-the-ground research in West Africa. “Contrary to the dominant assertion that Chinese companies operating in Africa tend to rely on labour imported from China, in most of the eighty-five Chinese enterprises we studied in Ghana and Nigeria, a substantial proportion, and often the majority, of the workforce was African.”37

South African president Cyril Ramaphosa recently spoke of South Africa’s experience with Chinese companies: “When China invests, it sends key managers, but the bulk of the people who do the work are South Africans.”38 Similarly, Namibian president Hage Geingob stated earlier this year that “no country in the world has added so much value to our products as China has. China has done a lot of technology transfer and job creation.”39

Early-stage projects, particularly in countries where China has little experience, tend to be staffed primarily by Chinese employees, but the clearly emerging pattern is for this ratio to be reversed over time.

China has caught Africa in a debt trap

A recent article by John Pomfret in the Washington Post describes Chinese investment strategy as “imperialism with Chinese characteristics”, and claims that “China’s debt traps around the world are a trademark of its imperialist ambitions.”40 Grant Harris, Barack Obama’s former adviser on Africa, writes that “Chinese debt has become the methamphetamines of infrastructure finance: highly addictive, readily available, and with long-term negative effects that far outweigh any temporary high.”41 Rex Tillerson, US secretary of state until his recent replacement by the even more hawkish Mike Pompeo, commented in March that “China’s approach has led to mounting debt and few, if any, jobs in most countries.”42

Such scare-mongering statements ignore the rather important detail that, “from 2000 to 2016, China’s loans only accounted for 1.8 percent of Africa’s foreign debts, and most of them were invested in infrastructure.”43

Investment generally entails some level of debt; the question is whether African countries are getting a good deal. Chinese investment is welcomed across the continent, since it is overwhelmingly directed towards essential projects: developing infrastructure, building schools, building hospitals, cleaning water, supplying electricity, building factories. As a result, the needs of ordinary Africans are being met, and the debts are typically repaid in a sustainable (and fairly negotiated) way using the host countries’ natural resources.

Chinese loans tend to be significantly lower interest than the equivalents from the Bretton Woods institutions and the major western banks; many are interest-free. Furthermore, there have been several rounds of debt relief, where the debts of the poorest African countries have been written off. The recent FOCAC summit promised $60 billion worth of new investment, including $15 billion of grants, interest-free loans and concessional loans, as well as $5 billion specifically to support the importing of African produce to China. Cyril Ramaphosa noted that “if some African countries can’t keep up with their debt payments, the debt will be forgiven”.44 By no reasonable definition is this a “debt trap”.

China is grabbing African land

In recent years, numerous headline-grabbing articles have claimed that China is in the process of sending millions of peasants to Africa in order to grow food for China.45 China is, apparently, a “land grabber”, a rising colonial power. And yet, “no one has yet identified a village full of Chinese farmers anywhere on the continent. A careful review of Chinese policy shifts shows steadily rising support for outward investment of all kinds but no pattern of sponsoring the migration of Chinese peasants, funding large-scale land acquisitions in Africa, or investing ‘immense sums’ in African agriculture. Finally, according to the United Nations Commodity Trade database, it is China that has been sending food to Africa. While this could (and should) change, so far, the only significant food exports from Africa to China have been sesame seeds and cocoa, produced by African farmers.”46

A mutually beneficial friendship

Accusations of Chinese imperialism in Africa, typically levelled by apologists for western imperialism,47 are not substantiated by facts. China’s development model isn’t based on, and has never been based on, colonial exploitation. On the contrary, China is keen to see Africa emerge as a key player in a multipolar world in which a relatively even balance of forces acts to preserve global peace and stability. This explains, for example, China’s enthusiastic support for the African Union and its commitment to the AU’s development agenda.48 That China’s engagement is a positive thing for Africa is evidenced by the near-universal enthusiasm for it among African governments (it’s telling to note that twice as many African heads of state attended the FOCAC summit than the recent meeting of the UN General Assembly).49

It’s hardly surprising that the concept of multipolarity is not universally esteemed within the imperialist heartlands. In particular the US ruling class is struggling to come to terms with the end of its uncontested hegemony; hence the desperate bid to ‘Make America Great Again’, which really means re-asserting US global dominance and taking the Chinese down a peg or two. The last thing the western ruling classes want to see is a thriving multipolarity based on mutually beneficial cooperation between independent states, bypassing and perhaps even ignoring the mandate of Washington, London and Paris. When people issue slanders about Chinese colonialism, they are feeding a narrative that seeks to maintain the imperialist status quo, even though they generally take the form of ‘concerned advice’. Such slanders should be resolutely exposed.