This post was updated on 7 April to reflect the updated situation and to include some discussion on the impact of Brexit on Ireland.

The date set for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union, 29 March 2019, is now in the past. The Brexit deadline has been extended, and is likely to be extended again. MPs can’t agree on what a deal should look like, only that the deal presented by the government isn’t very good. Labour and the Tories are in negotiations with a view to finding common ground on a softer Brexit, but at the time of writing we still don’t have much clue what the outcome will be. Will Theresa May finally be able to get her deal through parliament? Might we leave with a ‘Norway-plus’ type of arrangement, retaining membership of the Customs Union and potentially the Single Market? Might we leave without a deal, leading to probable economic crisis and social chaos? Or could there be a lengthy postponement, or could the whole thing be cancelled?

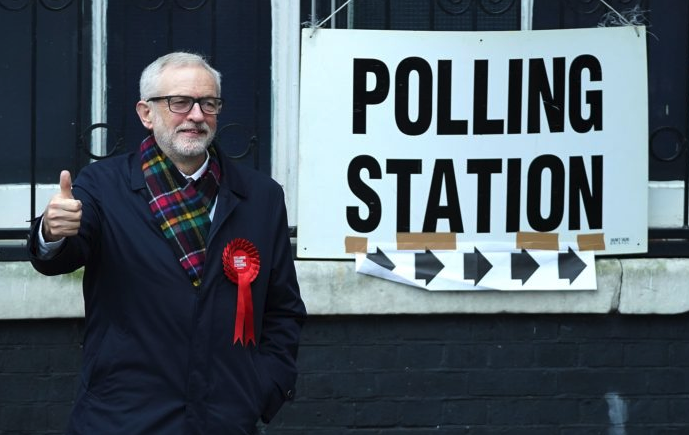

Absurdly, much of this uncertainty comes down to seemingly insurmountable divisions within the Conservative Party, and to the government’s prioritisation of its own petty interests over those of the British people – not to mention a desperation on the part of the British ruling class to keep Jeremy Corbyn as far as possible from 10 Downing Street.

Of course, those of us on the left can’t control what ruthless Tory Brexiters do. What we can and should do is develop a reasonable, coherent strategy of our own; a strategy with the power to unite a wide array of forces with the critical mass to defeat the anti-democratic and anti-popular machinations of the Tories and their chums on the extreme right. In so doing, we can avert disaster and strengthen the position of the working class.

A united strategy needs to be based on a detailed and realistic understanding of what Brexit is and what class forces it represents. As it stands, this understanding is largely absent. The ‘remain’ side of the debate has been dominated by liberal/centrist voices, including the likes of Tony Blair, Chuka Umunna and others trying to leverage the political crisis to weaken Corbyn. The bulk of the non-Labour left – including the Communist Party of Britain, the Socialist Party, Counterfire, the Socialist Workers Party – has been promoting a ‘Lexit’ line based on a combination of misunderstanding and wishful thinking, and in some cases with a dose of chauvinism. Even within the Labour left and the trade unions, there’s a reluctance to really articulate a coherent progressive vision (or systematic opposition to Tory Brexit) owing to worries about alienating people in pro-Brexit Labour-voting constituencies.

Without this understanding and the strategy that flows from it, we’re sleepwalking into a nightmare that will strengthen the most reactionary elements of the ruling class and that could set back progressive forces for a generation.

This article will attempt to show that the Brexit project serves the interests of a tiny finance-capitalist elite; that it represents an attack on working class conditions and unity; that it strengthens rather than weakens imperialism; that it will lead to greater inequality and poverty; that it is, in fact, a neoliberal scam that could have a devastating impact on the poorer sections of British society.

Neoliberalism on steroids

From the point of view of the millionaires who funded the leave campaign, the purpose of Brexit is to allow business to escape the public protections the EU provides. (George Monbiot)

Millions of people voted for Brexit. Their motivations were many and complex – including an amorphous idea of “taking back control”, old-fashioned xenophobia and anti-immigrant scapegoating, as well as a healthy middle finger to the smug status quo so amply represented by then-prime minister David Cameron. Very few of them voted for neoliberalism or deepening austerity; very few thought that the important thing was to reduce restrictions on big business such that it can exploit more ruthlessly and generate ever more fabulous profits. As Fintan O’Toole points out: “for most of those who voted for it, Brexit means a ‘return to the nation state’. But for many of those behind it, there is a very different ideal. They use this language because it is the only one that is politically viable. But for them the exit from the EU is really a prelude to the exit from the nation state into a world where the rich are truly free because they are truly stateless” (Heroic Failure: Brexit and the Politics of Pain, Apollo, 2019).

For many left-wing supporters of Brexit, the whole point is to break with neoliberalism, not strengthen it. They see the EU as the standard-bearer of free-market fundamentalism in the present era, forgetting that, within Europe, Britain was the first country to enthusiastically venture into the brave new world of massive deregulation. In the early 1980s, it was Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and Bob Hawke that led the neoliberal charge. Indeed, it took quite a long time to convince continental Europeans to pick up the baton. While Britain participated in the process of European integration through the development of the European Economic Community (EEC) and then the EU, this participation was always reluctant and partial, precisely because of British capital’s distrust for the relatively softer, more regulated version of capitalism pursued on the continent. Nothing could reconcile Thatcher and her friends to the concept of a “platform of guaranteed social rights”.

Even today, after a quarter of a century of deepening alignment with the new economic orthodoxy, France and Germany are far less ‘business-friendly’ environments than Britain (both charge around 30 percent corporation tax, for example). While the UK ranks 7th globally in the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, Germany ranks 24th and France 71st.

The EU mandates a level of protection for workers, it restricts off-shoring and tax avoidance, and it attempts to regulate the activities of the big banks. When the EU proposed a ‘Tobin tax’ on financial transactions in 2013, it was the British government that led the opposition to anything that limited the profits of the mega-rich. Boris Johnson, then London’s mayor, was viciously opposed to any increase in the EU’s regulatory reach: “We cannot allow jobs, growth and livelihoods to be jeopardised by those in the EU who mistakenly view financial services as an easy target.”

Jeremy Corbyn was 100 percent correct when he pointed out that “people in this country face many problems, from insecure jobs, low pay and unaffordable housing to stagnating living standards, environmental degradation, and the responsibility for them lies in 10 Downing Street, not in Brussels.”

‘Taking back control’ doesn’t mean assigning any new powers to the ordinary people of Britain. It means reducing EU regulations on British business. The idea isn’t even to reassign these powers to Whitehall but to get rid of them altogether. In a world where multinational corporations and financial institutions are too big to be subjected to any meaningful pressure by national governments like the UK, freeing themselves from supranational regulatory bodies like the EU means freeing themselves from oversight. It’s not just ‘small government’, it’s no government.

Few have articulated this fundamentalist Thatcherite vision more clearly than Nigel Lawson, former Chancellor of the Exchequer and president of the fanatically pro-Brexit ‘Conservatives for Britain’ pressure group. Writing in the Financial Times in September 2016, he complains bitterly that while “the Thatcher government of the 1980s transformed the British economy … through a thoroughgoing programme of supply side reform, of which judicious deregulation was a critically important part”, this process was limited by the “growing corpus of EU regulation”. Now, however, “Brexit gives us the opportunity to address this; to make the UK the most dynamic and freest country in the whole of Europe: in a word, to finish the job that Margaret Thatcher started”.

The Brexit engineers are involved in the construction of a Thatcherite neoliberal paradise that will bring fabulous profits to a few capitalist buccaneers, and ever-increasing misery to those at the bottom of society.

A boost for the Atlanticists

Brexit was not, to my mind at least, a choice between the EU and ‘independence’, but a choice between staying part of a flawed union or choosing to deepen ties with the American Empire and continue the ‘Americanisation’ of the British economy. If Britons wish to learn what a US-style healthcare service looks like, they are free to talk to any poor American (Akala, Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire, Two Roads, 2018).

There’s a widespread assumption that the British ruling class is overwhelmingly opposed to Brexit. This is not the case; the ruling class is deeply divided on Brexit. The line of division is essentially between a relatively European-aligned section of British capitalism and a relatively US-aligned ‘Atlanticist’ section. This reflects deeper economic and strategic divisions: the Atlanticist ruling class is more connected to finance capital, to the military-industrial complex, and to Big Oil; its political orientation is closer to an openly aggressive, racist Trump-ism than to the relatively more sophisticated approach of Obama or Merkel. The last time this division was manifested so starkly was in 2003, when the British ruling class was split as to whether to join the US war on Iraq or to support the French/German position against the war.

The leading pro-Brexit politicians – Boris Johnson, Michael Gove, Nigel Farage, Jacob Rees-Mogg, David Davis, Liam Fox, Dominic Raab, Iain Duncan Smith and Steve Baker – are all noted Atlanticists. Liam Fox for example has consistently maintained a pro-US orientation, including strongly favouring close military alliance. His charity, Atlantic Bridge, exists to promote close coordination between the Conservative Party and the hard-right Tea Party nutcases in the Republican Party. Boris Johnson is a wholehearted supporter of Making America Great Again, close with both Donald Trump and Steve Bannon. Trump, Bannon and John Bolton are all fond supporters of the Brexit project, as is Rupert Murdoch. The multi-millionaire financiers of the Brexit campaign – people like Arron Banks, Peter Hargreaves, Peter Cruddas, Stuart Wheeler, Michael Hintze, Martin Bellamy, Jon Moynihan and Robert Hiscox – all favour closer links with the US. They are certainly not motivated by any overarching desire to weaken imperialism or empower the working class.

Brexit is a key component of Trump’s ‘America First’ strategy. It’s instructive that the Heritage Foundation, a highly influential neoliberal think-tank in the US and a major force in the Trump administration, has lobbied for Brexit over the course of over a decade on the basis that it will strengthen the US’ hand in the global economy and help to weaken the EU. British political analyst TJ Coles gives a helpful summary of Heritage’s changing attitude towards the EU: “The Heritage Foundation describes America’s initial interest in a United Europe as a bulwark against the Soviet Union… As there is now no Soviet Union, there is no need for a United Europe. A regulated European Union, which erects barriers to US products and services (such as labels identifying genetically-modified foods and regulations against privatisation) is bad for America’s corporate profits. After the financial crisis of 2008, Europe’s central command in Brussels started regulating financial markets in an effort to prevent another crash. The Heritage Foundation report analyses America’s efforts to use Britain as a ‘Trojan Horse’ to push through state deregulation in Europe. As Britain was not powerful enough to do this, America felt that a weakened Europe would better serve its financial and trade interests” (The Great Brexit Swindle, Clairview, 2016).

Leaving the EU Single Market, Britain will not suddenly become a major economic player in its own right; its economic strength and geographic location make that impossible. With the imposition of tariffs between Britain and its biggest trading partner, Britain will be forced to look elsewhere for a major trade deal. That means, first of all, a ‘free trade agreement’ with the US, the terms of which will be dictated by the latter. As Tom O’Leary writes, “the terms of negotiations between the UK and US will reflect the real relationship of forces between the two economies. The US economy is approximately 6.5 times greater than the UK economy… For the Trump negotiators, there are ten economies in the world whose GDP is greater than or more or less equal to that of the UK (on a PPP basis). It will be the UK which is desperate for a deal, not Trump… Any new deal is unlikely to compensate for the lost trade with the EU and will come at a significant price, in terms of workers’ rights, environmental protections, consumer safeguards and the privatisation of UK public services.”

Deepening division of the working class

It is sometimes easier to blame the EU, or worse to blame foreigners, than to face up to our own problems. At the head of which right now is a Conservative Government that is failing the people of Britain (Jeremy Corbyn, April 2016).

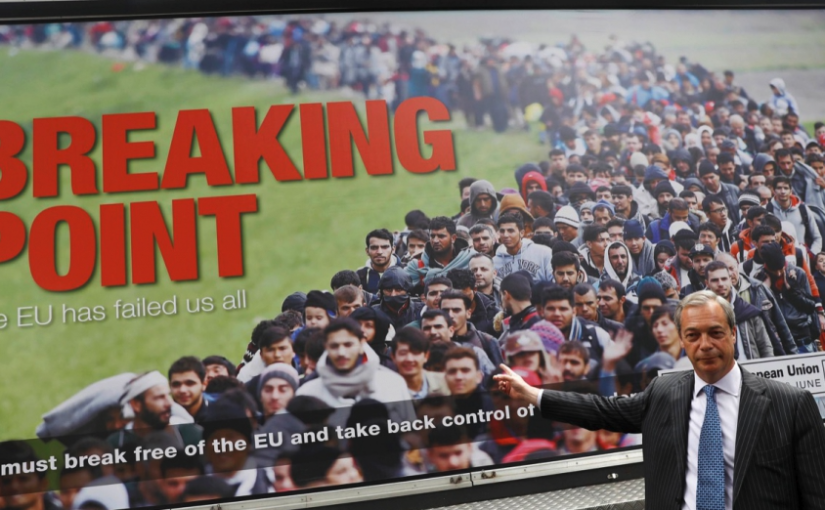

Polling has consistently shown that anti-immigration sentiment was the one of the key motivating factors in the Brexit referendum. A fairly typical study found that nearly three-quarters of Leave-voters were worried about immigration levels. Brexit campaigners shamelessly leveraged this latent xenophobia, with Nigel Farage’s infamous ‘breaking point’ poster being a particularly nasty example, along with Boris Johnson and Michael Gove repeatedly using Turkey’s aspiration of EU membership as a pro-Brexit scarecrow. As Aditya Chakrabortty pointed out, “One didn’t need especially keen hearing to pick that up as code for 80 million Muslims entering Christendom.”

This type of message was particularly effective, since it was essentially a reiteration of the racist language of the Tory mainstream. A study by Kings College London found that media coverage of immigration issues “more than tripled during the ten-week Brexit campaign, rising faster than any other political issue and appearing on 99 front pages, compared with 82 about the economy. Most of these front pages (79) were published by pro-leave newspapers.”

Although Theresa May campaigned (very half-heartedly) to remain in the EU, she didn’t feel strongly enough about it to counter anti-immigrant propaganda, instead choosing to suppress multiple studies showing that immigration doesn’t lead to lower wages. Plus of course she was the architect of the ‘go home’ vans, the hostile environment, and the chief culprit of the Windrush debacle. The Remain campaign was mainly defensive on the issue of immigration, choosing not to promote an anti-racist narrative. Of the prominent Remain supporters, it was only Jeremy Corbyn and his close circle in the shadow cabinet – along with the SNP, Greens and Plaid Cymru – that actively defended immigration. When they did so, they were either ignored or ridiculed by the press.

Fintan O’Toole writes that the Brexit vote “depended on an ostensibly improbable alliance between Sunderland and Gloucestershire, between hard old steel towns and rolling Cotswold hills, between people with tattooed arms and golf club buffers” (op cit). This unlikely convergence was mediated by decades of anti-immigrant rhetoric; of old-fashioned scapegoating that blamed immigrants for the problems of capitalism.

Survey data indicates that a significant majority of the British population would like immigration numbers to be reduced, presumably believing – incorrectly – that immigration adversely impacts quality of life. This prejudice contributed more than any other single factor to the Leave vote; there’s absolutely no chance a majority would have voted for Brexit were it not for the promise of reduced immigration. This was recognised by Britain’s ethnic minority communities, which invariably voted in large majorities to remain in the EU. The racism of the Brexit campaign is demonstrated with appalling clarity by the staggering increase in hate crime incidents in the weeks following the referendum.

Taking charge of the Brexit negotiations, Theresa May made it clear from the beginning that her priority was to restrict freedom of movement. Brexit means Brexit means xenophobia.

This xenophobia is not of course exclusively connected to Brexit; it was leveraged by the Brexiters in order to win the referendum, but it has a broader political purpose for capitalism: preventing unity of a multicultural multi-ethnic working class. The specific form of racism surrounding the Brexit campaign also chimes with cultural changes in Britain in recent decades. The brutal, flagrant racism that was meted out in previous decades to Irish, Jews, African Caribbeans, Asians and others is no longer socially acceptable in the way it was. Instead we have what Ambalavaner Sivanandan described as ‘xeno-racism’ – “it is racism in substance, but ‘xeno’ in form. It is a racism that is meted out to impoverished strangers even if they are white.” Those immigrants “coming over here and taking our jobs” are nowadays less likely to be Asians and Caribbeans, but rather Romanian and Polish – not to mention Nigel Farage’s asylum seekers and Boris Johnson’s Turkish EU citizens. Brexit has managed to both leverage and deepen this racism, and in so doing has strengthened the hand of the most reactionary elements of British society.

Brexit will make workers poorer

Brexit will harm large sections of the British economy, and the cost of this damage will inevitably be borne by the working class, since the owners of capital can more easily shift their investments to those areas that aren’t affected. As TUC General Secretary Frances O’Grady notes: “Other EU countries buy huge amounts of British goods and services. But if it’s harder to sell what the UK makes in Europe, big global firms are likely scale down their operations. That would result in big job losses, especially in sectors like manufacturing where half of exports go the EU.” These manufacturing jobs, threatened by Brexit, are typically paid significantly better than their service sector equivalents, so “even if jobs lost were replaced, we’ll be left with worse jobs on lower wages.”

The EU is Britain’s largest trading partner, constituting 44 percent of exports and 53 percent of imports. The TUC estimates that over three million jobs in Britain are linked to trade with the EU. Outside the EU single market, it will be more difficult to sell products and services made in Britain and to buy products and services from elsewhere. In the short term, this puts essential imports such as food and medicine at risk – Britain imports around 40 percent of its food, for example, and the vast majority of this comes from the EU. In the longer term, it leads to reduced productivity and reduced participation in the international division of labour. Tom O’Leary writes that, post-Brexit, “the economy will be operating behind a series of tariff and non-tariff barriers as others protect their markets. All of these will make the economy less competitive and will increase costs.” This cannot but have a detrimental effect on living standards.

EU funding in Britain will end immediately with Brexit. This will have a disproportionate impact on the poorer regions of the UK, particularly in Cornwall, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Even more significant would be the effect on public finances due to businesses closing or moving away from Britain, as well as from reduced immigration. The Economist puts the case bluntly: “Britain exports old, creaky people and imports young, taxpaying ones. More than 100,000 British pensioners live it up in sunny Spain; meanwhile, up to 100,000 working-age Spaniards brave the British cold… The government’s fiscal watchdog suggests that by the mid-2060s, with annual net migration of about 100,000, public debt would be roughly 30 percentage points higher than if that figure were 200,000. Taking back control comes with a whopping bill.” Beyond fiscal revenue, reduced immigration means a lack of people to do important work. For example, the staffing crisis in the NHS is expected to get much worse with Brexit.

For the myriad flaws of the EU, membership has brought some crucial benefits to British workers. As Jeremy Corbyn has pointed out, “there was no limit on working time for workers in Britain until the Working Time Directive, which also provided for rest breaks. Our rights to annual leave were underpinned by the EU too; we would not have a right to 28 days’ leave without that membership.” EU regulations mean that part-time workers (predominantly women) have equal rights with full-time workers; that a million temporary workers have the same rights as permanent workers. Freedom of movement means that these terms can’t (legally) be undercut within the EU – so ending freedom of movement would significantly deepen the ‘hostile environment’ in terms of labour rights for immigrants.

In the same 2016 speech, Corbyn pointed out that the most ruthless exploitation in Britain is not the result of EU neoliberal policy; in fact most EU countries are far better than Britain in terms of workers’ rights. “If we want to stop insecurity at work and the exploitation of zero hours contracts why don’t we do what other European countries have done and ban them? Zero hours contracts are not permitted in Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Poland and Spain.”

Outside the customs union, Britain will need to negotiate major trade deals. The most prominent of these is with the US, which will be well placed to exact horrific terms, including opening up much more of the NHS and education system to privatisation. As TJ Coles writes, “a Britain unshackled from Europe would strengthen US-UK relations and weaken the EU in preparation for a regulatory assault by the US” (op cit).

Post-Brexit trade deals will almost certainly mean opening up the British market for dangerous produce. As it stands, the EU bans the import of US-produced items such as hormone-treated pork and beef, genetically-modified cereals, and chlorine-washed chicken. US capital and its Tory allies are desperate to put an end to these restrictions, and Brexit gives them the perfect opportunity.

Brexit means worse conditions for workers. More casualisation, more privatisation, less regulation, less union power, fewer restrictions on big business. This is exactly why a significant section of the British ruling class is so keen on Brexit, and why the rest of us should resolutely oppose it.

EU state aid rules are not the problem

The proponents of Lexit, both within and outside the Labour Party, have built their case primarily on the idea that EU regulations regarding state aid to industry will stand in the way of a programme of state-led investment and nationalisation. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has unfortunately lent credence to this theory.

There are three major problems with this. The first is a simple practical matter: Jeremy Corbyn is not the prime minister, and Labour is not in government. Efforts to change that situation are welcome and necessary, but it is very likely the Tories that will be implementing Brexit, and the Brexit they have in mind has nothing whatsoever to do with nationalisation and the redistribution of wealth. Quite the opposite. However problematic the EU state aid rules might be, the British post-Brexit government is highly unlikely to replace them with anything better.

The second problem is that Labour’s ‘Soft Brexit’ wouldn’t release Britain from EU state aid rules. The Labour leadership has repeatedly stated that its Brexit vision includes continued membership of a comprehensive customs union with the EU. The chances of the EU signing up to such a deal whilst allowing exemptions on its core elements are approximately nil.

The last obvious problem with the idea that EU state aid rules get in the way of public ownership is that it’s not actually true. Britain’s relentless privatisation over the course of the last 40 years has been pushed by successive British governments; it has been cooked up in Whitehall, not Brussels. In fact, as TSSA general secretary Manuel Cortes notes, “Britain spends far less than the EU average on state aid. If Britain were to match the proportion of spending of Denmark it would mean an extra £24 billion a year; if Britain matched Hungary, we would spend an additional £34 billion.”

George Peretz QC, a barrister specialising in public law and tax issues, writes that, “as far as nationalisation is concerned, EU law raises no objection. Anyone who knows the continent knows that in most countries most operators in the sectors mentioned by Corbyn [postal services, water, railways and banks] are state-owned… Many member states have been able to provide large subsidies to their rail and postal operators to ensure high quality universal services… What the state aid rules prevent is ill-targeted aid, such as the money repeatedly thrown down the black holes of national flag carriers or tax exemptions given to large multinational companies in return for locating in the state concerned.” In short, the EU state aid rules would have little or no impact on the progressive programme of state-led investment envisaged by Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell.

Britain leaving the EU will not weaken imperialism

Another Lexit idea is that the EU – an organisation composed of capitalist countries – will be diminished by the UK’s departure, and therefore imperialism as a whole will be weaker. This rather ignores the fact that Britain was an imperialist country before joining the EU and will remain an imperialist country once it leaves. Because the UK will, for reasons described above, lean more towards the US (which by any reasonable definition represents the most aggressive form of imperialism on the planet in the present era), the balance of forces between imperialist blocs will be shifted somewhat, but not in a way that benefits the masses of the world seeking to free themselves from neocolonial domination.

Laughably, some of the leading Brexiters have talked about Britain’s departure from the EU paving the way for the establishment of an ‘Empire 2.0’ built on stronger trading links within the Anglosphere and the Commonwealth. This is the stuff of sheer nostalgic fantasy. In truth, as pointed out by Tottenham MP David Lammy, “leaving the EU will not free us from the injustices of global capitalism: it will make us subordinate to Trump’s US.” Britain is not a major player in the global economy any more; Brexit has come a century or so too late for these nutty delusions. If an ‘Empire 2.0’ were to come into being, “its centre would not be in London but in Washington. It would be an American, not a British empire” (O’Toole, op cit).

In foreign policy terms, Brexit stands to push Britain towards a more aggressively reactionary position. Ministers are already talking about how they’ll be able to ramp up sanctions against Russia, for example. Aligned to Trump’s US, Britain would be under intense pressure to join the sanctions regime against Iran, to support US policy on trade with China, and to scale back participation in global environmental cooperation. Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson has made it all too clear that “Brexit represents an opportunity for Britain to boost its global military standing in response to the threats posed by Russia and China”.

From a strategic anti-imperialist point of view, a relatively stronger EU and relatively weaker US would constitute a more favourable balance of forces; this much was recognised by Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2015: “China hopes to see a prosperous Europe and a united EU, and hopes Britain, as an important member of the EU, can play an even more positive and constructive role in the promoting the deepening development of China-EU ties.” The subtext is clear enough: a US-dominated unipolar world is the most dangerous possible scenario.

There is also the profoundly important issue of Ireland to consider. Brexit poses a serious threat to the Irish economy in both north and south, to the Good Friday Agreement, and to the wider cause of Irish unity and self-determination. The peace process has turned the hard border into a soft border, with an increasingly integrated economy and a much-reduced presence of the British armed forces on the streets of the north. These streams have fed into a powerful (albeit slow and winding) river headed towards peaceful reunification.

Brexit will inevitably affect economic cooperation between north and south, and, if the hard-Brexiters get their way, could well dismantle all the progress of the last two decades. A land border and customs checks would be extremely disruptive and would contravene the terms of the GFA. This would lead to rising dissatisfaction and, very likely, increased sectarian tensions. With a coalition of the Democratic Unionist Party and the Conservative and Unionist Party in power in Westminster – probably with an even more nutty right-wing leadership than at present – we could well see an increased presence of the UK armed forces, under the direction of an emboldened, militantly unionist government that wouldn’t hesitate to employ any measure in defence of the union. Various commentators have noted that a no-deal Brexit could mean a return to direct rule. There’s nothing anti-imperialist about that.

Remain and reform

None of this is to claim for the EU any progressive nature. The precursor organisation to the EU was formed as a bulwark against Soviet socialism and to represent the interests of US-dominated western capitalism in Europe. The need to provide European workers with an alternative to socialism meant that the European Economic Community tended to promote a relatively benign, social-democratic form of capitalism. With the decline and fall of the Soviet Union and its Central/East European allies, the neoliberal consensus seeped out of the Anglosphere and into the heart of Europe. As Fintan O’Toole writes: “Being angry about the European Union isn’t a psychosis – it’s a mark of sanity. Indeed, anyone who is not disillusioned with the EU is suffering from delusions. The slow torturing of one of its own member states, Greece, was just the most extreme expression of a desire to blame the debtor countries alone for the great crisis that hit the Eurozone in 2008” (op cit).

However, as noted above, the neoliberal consensus was not invented by the EU, and the EU is not responsible for imposing it on Britain. Within the EU, leftists in Britain are better placed to fight free-market fundamentalism across the continent. In the words of Manuel Cortes: “Solidarity means standing shoulder to shoulder with our sisters and brothers in socialist parties across the EU demanding a Europe for the many as an integral part of building a better world.” This was precisely the meaning of Corbyn’s “Remain and Reform” slogan. There are plenty of examples of a progressive agenda being successfully advanced within the EU; indeed, the various protections for workers currently embodied in EU regulations were won through continent-wide class struggle.

Where do we go from here?

The progressive project represented by Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party could provide the basis for an unprecedented unity in this country. The NHS and the welfare state are among the best things the British people have created. We are well placed to expand and innovate in these areas, along with green energy, poverty alleviation, inequality reduction and scientific research; we can develop a global outlook that embraces multipolarity and opposes war. But any prospects for a successful socialist-oriented government in Britain would be seriously undermined by a Tory Brexit that would be accompanied by economic crisis, deep social divisions and a foreign policy designed by John Bolton.

It would be much better to remain in the EU than to proceed with this hard-right scam. It is the duty of all socialists and progressive people to do everything within their power to avoid a “hard Brexit” or a “no-deal Brexit”. Preferably this means remaining in the EU, but if this isn’t possible, we should work towards Brino – Brexit in name only. Labour has taken some steps towards that sort of position, pushing for a comprehensive, permanent customs union with the EU. However, the EU negotiators have repeatedly made clear that any customs union would be conditional on maintaining free movement of labour. The next critically important step for the Labour leadership and the trade unions is to unambiguously accept freedom of movement. That shouldn’t be difficult, because freedom of movement is a fundamentally positive thing. It benefits both immigrants and non-immigrants. The numbers show again and again that immigrants are net contributors to the economy. Indeed, our economy is heavily reliant on immigration. With freedom of movement, immigrants coming here from the EU are protected by EU-wide labour legislation which means they can’t be ruthlessly exploited at the levels British capital would like. If those protections were taken away, it would drive down wages and conditions for everyone. And besides the economic aspect, there is the basic political principle of promoting maximum unity of the working class. Any sheepishness or caginess about this issue feeds into a growing, dangerous trend of racism and xenophobia.

We should recognise the Brexit project as a multi-pronged attack on the working class, and we should take all necessary measures to defend ourselves against it.