This is the first in a series of eight articles regarding the collapse of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR, or Soviet Union). Although a distance of more than 25 years separates us from that fateful day in 1991 when the USSR ceased to exist, the left’s understanding of the Soviet collapse is still limited and many of the important themes are poorly understood.

Why dig up these particular old bones? Because we must reflect on, and learn from, history. The world’s first socialist state no longer exists, and nor do the European people’s democracies that were its close allies. If mistakes were made, it’s crucial that they aren’t made again. Existing socialist states face many of the same external pressures that the Soviet Union faced; future socialist states almost certainly will too. Additionally, socialist states so far have had great difficulty maintaining revolutionary momentum through the second, third and fourth generations of the revolution; this is as true of contemporary Cuba or China as it was of the USSR. Addressing these problems is obviously essential, and the details of the Soviet collapse constitute some of the most important raw data for any such analysis. The more our movement can learn about the Soviet collapse, the better prepared we will be to prevent historic reverses and defeats in future, and the better equipped we will be to develop a compelling, convincing vision of socialism that is relevant to the here and now.

Needless to say, I don’t claim to have definitive answers. The disappearance of the USSR is a vastly complex subject, incorporating history, politics, economics, sociology, philosophy, military science, social psychology and more. Others know more and have done more thorough research than I have. The idea here is simply to present the historical outline, raise some questions, put forward a couple of hypotheses, and contribute to the ongoing debate. In terms of digging deeper into the subject, I’d point the reader towards the following very useful books. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses, but all contain valuable insight on the topic of the Soviet collapse and have been of inestimable help in terms of forming my own opinions.

- David Kotz and Fred Weir: Revolution From Above1

- Roger Keeran and Thomas Kenny: Socialism Betrayed2

- Vijay Prashad: Red October3

- Michael Parenti – Blackshirts and Reds4

I make no apologies for taking a partisan perspective; of defending the achievements of the Soviet Union; of being on “the workers’ side of the barricades” in the global class war between imperialism on the one hand and, on the other, the socialist countries, the exploited nations, and the workers and oppressed masses in the imperialist heartlands. If the reader is looking for a triumphalist, anticommunist account of the Soviet demise, such a thing can easily be found, but not here. My starting point is that the immense problems faced by humanity cannot be solved within a political-economic framework of capitalism; that the transition towards socialism and, ultimately, communism is both desirable and necessary.

The broad themes that will be covered in this set of articles are: the positive achievements of the Soviet Union; mounting economic difficulties in the 1970s and 1980s; ideological decay and dissatisfaction from the 1950s onwards; Reagan, Afghanistan, the arms race and the ‘full-court press’; Mikhail Gorbachev and his perestroika and glasnost; the events of the chaotic last couple of years of the USSR’s existence (1990-91); the effects of the counter-revolution both in the former USSR and throughout the world; and whether the People’s Republic of China is likely to suffer the same fate as its socialist forerunner.

But wasn’t the Soviet experiment a dismal failure?

Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter. (African proverb)5

Over a quarter of a century after the collapse of the USSR and the end of the Cold War, the history of that country as told by mainstream historians is that it was a horrific, criminal enterprise; that Soviet socialism was the very antithesis of freedom and democracy; that the whole experiment was an unmitigated failure that has its clear antithesis in the success of western free market democracy. This is all received wisdom in Western Europe and North America, to such a degree that when anyone in the media spotlight questions this purported truth, they’re treated like members of the Flat Earth Society.6

All this rather helpfully feeds into what is surely the most important theme of modern politics, economics, history, philosophy and sociology: communism is a wrongheaded and illogical ideology that contradicts the very essence of human nature.

Even within the political left, few are those that bother defending the record of the Soviet Union any more. We throw up our hands and say “we still believe in socialism, but the Russians got it wrong”. Perhaps true socialism has never been built; perhaps early 20th-century Russia, with its economic backwardness and vast peasant majority, wasn’t a suitable environment for such an ambitious project; perhaps socialism was perverted and destroyed by the venality and ruthlessness of the Soviet leadership, in particular Joseph Stalin.

Whichever variant of the ‘failure’ narrative you choose, you’re left with no special difficulty explaining why, on 31 December 1991, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics ceased to exist: it was a failed experiment, and failed experiments must eventually come to an end.

In many respects, the USSR was incredibly successful

The path traversed by the Soviet Union over the last sixty years is equivalent to a whole epoch. History perhaps has never known such a spectacular advance from a condition of backwardness, misery and ruin to the grandeur of a modern great power with highly advanced culture and steadily growing welfare of the people.7

In reality, the task of understanding the Soviet implosion is not so simple. The Soviet Union has several world-historic achievements to its name. In the Soviet period, the peoples of the territories of the Soviet Union experienced an unprecedented improvement in living standards. Feudal property relations and backwardness were wiped out, and the Soviet Union emerged as a superpower – the second biggest economy in the world, at the cutting edge of science and technology. For the first time in Russian history, the curse of famine was defeated. European fascism was defeated, largely through the efforts, sacrifices, heroism and creative brilliance of the Soviet people. Soviet people built and enjoyed the world’s first comprehensive welfare state. Nobody that was willing and able to work went without work. Education and healthcare were comprehensive and free. Housing was often cramped, but universal and inexpensive. For the first time in history, the political and cultural supremacy of the working class was established: the government derived its credibility on the basis of how well it served the masses, not the wealthy. With the aid of the Soviet people, liberation movements around the world were able to break free from the shackles of colonialism and imperialism.

Mocking the histrionic anticommunism of mainstream historians, Michael Parenti writes:

To say that “socialism doesn’t work” is to overlook the fact that it did. In Eastern Europe, Russia, China, Mongolia, North Korea, and Cuba, revolutionary communism created a life for the mass of people that was far better than the wretched existence they had endured under feudal lords, military bosses, foreign colonisers, and Western capitalists. The end result was a dramatic improvement in living conditions for hundreds of millions of people on a scale never before or since witnessed in history… State socialism transformed desperately poor countries into modernised societies in which everyone had enough food, clothing, and shelter; where elderly people had secure pensions; and where all children (and many adults) went to school and no one was denied medical attention.8

Socialism in practice conclusively solved many of the worst of humanity’s problems; problems to which capitalism had not (and still has not) been able to resolve. Boris Ponomarev, a leading theoretician of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (and one of its more insightful representatives in the 70s and 80s), summarised in the following terms:

Socialism has ended for good the problem of unemployment which is the worst and most insurmountable social problem in the capitalist world. The countries of the socialist community have introduced blanket social security schemes covering the entire population, free medical care and education, guaranteed housing along with many other social blessings and economic rights enjoyed by one and all. Socialism has guaranteed equitable distribution of material and cultural benefits… Socialism has ended unequal pay for women and youth… The record of the Soviet Union as a multi-national socialist state convincingly demonstrates that the socialist system assures equal rights for all peoples, establishes relations of fraternal friendship among the peoples for dynamic economic and cultural progress.9

Starting from an extremely low base

In assessing the achievements of the Soviet Union, it’s important to recognise the low base from which it started. Pre-revolutionary Russia was characterised by widespread hunger, stark authoritarianism, obscene inequality, pervasive racist and antisemitic scapegoating, and brutal exploitation. Workers and peasants were denied access to even basic education. The bankrupt tsarist regime (and indeed the provisional government after the February 1917 revolution) thought nothing of sacrificing the lives of millions of ordinary people in the name of colonial expansion. As Kotz and Weir note in Revolution From Above:

In 1917 the Russian economy lagged far behind the dynamic capitalism of the great powers. In 1980, some sixty years after the Russian Revolution, the Soviet Union was one pole of a bipolar world. It had been transformed into an urban, industrialised country of 265 million people. By such measures as life expectancy, caloric intake, and literacy, the Soviet Union had reached the ranks of the developed countries. It gave economic and military aid to many countries around the world. It was a leader in many areas of science and technology. It launched the first space satellite. In some more prosaic fields, ranging from specialised metals, to machines for seamless welding of railroad tracks, to eye surgery equipment, it was a world leader. Its performing artists and athletes were among the world’s best. With its Warsaw Pact allies, it was the military equal of the United States-led Nato alliance.

For us, by us: ordinary people at the head of society

The Soviet Union was the first state to explicitly represent the demands of the working class and oppressed people. As Lenin put it, the significance of the revolution “is, first of all, that we shall have a Soviet government, our own organ of power, in which the bourgeoisie will have no share whatsoever. The oppressed masses will themselves create a power. The old state apparatus will be shattered to its foundations and a new administrative apparatus set up in the form of the Soviet organisations.”10

At the most basic level, the benefits of economic growth were directed towards ordinary people rather than a capitalist class. While GDP growth was generally respectable in the US, Western Europe and Japan in the post-war period, it had its clear counterpart in ever-widening inequality. The rich became much, much richer; conditions of life for the poor improved little. According to Albert Szymanski, “over the entire 1940-1980 period the real wages of Soviet factory and office workers increased by a factor of 3.7 times. By way of comparison it should be noted that the real wages of all US workers declined by about 1% a year over the 1970s and early 1980s.” Furthermore, in the Soviet Union, basic foodstuffs, housing and transport were all heavily subsidised. “Housing, medicine, transport and insurance account for an average of 15% of a Soviet family’s income, compared to 50% in the US, while such services as higher education and child-care are either free or heavily subsidised.”11

The Soviet Union was incomparably more egalitarian than the capitalist countries: “The income spread between highest and lowest earners in the Soviet Union was about five to one. In the United States, the spread in yearly income between the top multibillionaires and the working poor is more like 10,000 to 1.”12

Ending unemployment was a momentous breakthrough. The individual’s right to productive employment is recognised in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, and yet it is near-impossible to guarantee such a right under capitalism, which demands what Marx described as a ‘reserve army of labour’ (ie a significant number of unemployed workers) to exert downward pressure on wages. Conversely, in a socialist system, where the fruits of labour are shared by the people rather than being monopolised by the owners of the means of production (ie the capitalist class), the existence of unemployment is an unambiguous waste of resources, helping nobody. The Soviet Union was therefore the first modern industrial economy to eliminate long-term unemployment. The consequences of this in terms of people’s wellbeing are huge; after all, unemployment is widely regarded as the number one socio-economic problem in the capitalist world.13 The ‘The Red Dean of Canterbury’, Hewlett Johnson, spoke of the social impact of full employment and a welfare state in his classic study, The Socialist Sixth of the World, based on his numerous tours to the USSR in the 1930s:

The vast moral achievements of the Soviet Union are in no small measure due to the removal of fear. Fear haunts workers in a capitalist land. Fear of dismissal, fear that a thousand workless men stand outside the gate eager to get his job, breaks the spirit of a man and breeds servility. Fear of unemployment, fear of slump, fear of trade depression, fear of sickness, fear of an impoverished old age lie with crushing weight on the mind of the worker. A few weeks’ wages only lies between him and disaster. He lacks reserves.

Nothing strikes the visitor to the Soviet Union more forcibly than the absence of fear… No fear for maintenance at the birth of a child cripples the Soviet parents. No fear for doctors’ fees, school fees, or university fees. No fear of under-work, no fear of over-work. No fear of wage reduction, in a land where none are unemployed… So long as work is needed, work is free to all. Workers are in demand in the Soviet Union; and wages rise.14

Russia’s long and admirable traditions of music, literature and theatre were combined with the rich store of folk traditions from around the Soviet Union, producing a culture that was inclusive, accessible, innovative and proud. Most importantly, cultural life was not the preserve of the rich or the intellectuals, but was the collective property of the masses.

UNESCO reported that Soviet citizens read more books and saw more films than any other people in the world. Every year the number of people visiting museums equaled nearly half the entire population, and attendance at theatres, concerts, and other performances surpassed the total population. The government made a concerted effort to raise the literacy and living standards of the most backward areas and to encourage the cultural expression of the more than a hundred nationality groups that constituted the Soviet Union. In Kirghizia [Kyrgyzstan], for example, only one out of every five hundred people could read and write in 1917, but fifty years later nearly everyone could.15

Constructing a successful multinational state

Breaking with the brutal colonialism of the tsarist empire, the Soviet government succeeded in uniting dozens of nations and ethnicities into a multinational state based on mutual respect and tolerance. “Complete equality of rights for all nations; the right of nations to self-determination; the unity of the workers of all nations”16 was a highly advanced slogan anywhere in the political context of the early 20th century, but particularly so in Russia, that ‘prison house of nations’.

The resolution of the national question in the Soviet Union was a historic achievement. At the root of the Soviet approach was Marx’s famous teaching that “any nation that oppresses another nation forges its own chains.”17 Different nations, with their varying religions, ethnicities, histories and traditions, were brought together in a multinational state that actively worked to overcome the Russian chauvinism and domination constructed over centuries under the tsars. Formerly proud nations such as Azerbaijan and Georgia – vibrant centres along the Silk Road that had suffered tyranny and enforced backwardness as part of the Russian Empire – became equal players in a socialist union, in the process experiencing extraordinary improvements in living standards, education levels, access to cultural facilities, and so on. Samir Amin notes:

The Soviet system brought changes for the better. It gave these republics, regions, and autonomous districts, established over huge territories, the right to their cultural and linguistic expression, which had been despised by the tsarist government. The United States, Canada, and Australia never did this with their indigenous peoples and are certainly not ready to do so now. The Soviet government did much more: it established a system to transfer capital from the rich regions of the Union (western Russia, Ukraine, Belorussia, later the Baltic countries) to the developing regions of the east and south. It standardised the wage system and social rights throughout the entire territory of the Union, something the Western powers never did with their colonies, of course. In other words, the Soviets invented an authentic development assistance, which presents a stark contrast with the false development assistance of the so-called donor countries of today.18

Once radical movements in the Central Asian and Caucasian areas of the Russian Empire had established Soviet power, the new regimes immediately got on with the job of undoing the legacy of Russian domination, engaging in radical land distribution and giving land that had been seized by Russian settlers to local peasants. This was combined with “a wide range of economic, social and cultural improvements in people’s lives, including mass literacy campaigns, universal education, modernisation of agriculture, industrialisation, and the provision of basic medical and welfare services.”19

Held in a state of perpetual backwardness and colonial dependency by the tsarist regime, the eastern republics of the USSR experienced a period of unprecedented economic and cultural advancement, shared by the whole population. “Before the Bolshevik Revolution, the vast majority of the peoples of Soviet Asia were illiterate. Even in 1926, a decade after the Revolution, only 3.8% of the people in Tajikistan, 11.6% of those in Uzbekistan, 14.0% of those in Turkmenistan, and 16.5% of those in Kirghizia were literate; a high proportion of the literates were in fact Russian immigrants. By the end of the 1930s most people throughout the USSR were literate, and by the end of the 1950s literacy was virtually universal”.20 Compare this with capitalist India, where even today the literacy rate is only 74% – or perhaps more pertinently with Afghanistan, which shares a border and many cultural similarities with Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, where the literacy rate today is among the lowest in the world at 31% (17% for women).

Defeating racism

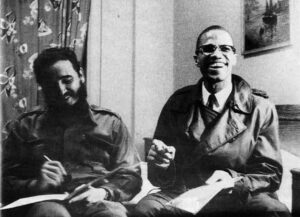

The Soviet people attempted to build a society free from racism. Just as “you can’t have capitalism without racism” (Malcolm X), the Soviet Union was built on the premise that you can’t have socialism with racism. The constitution was unequivocal: “Any direct or indirect restriction of the rights of, or, conversely, any establishment of direct or indirect privileges for, citizens on account of their race or nationality, as well as any advocacy of racial or national exclusiveness or hatred and contempt, is punishable by law.” The most palpable difference in these terms was the treatment of Jewish people before and after the revolution. Under the tsarist period, Jews had been subjected to vicious, violent anti-semitism, including officially-sanctioned pogroms. Russia had been a centre of the age-old European anti-semitic scapegoating that gave rise to the horrors of Nazism. “Jews were systematically excluded from privileged positions, and many were driven out of the country by discrimination and pogroms in the generation before the 1917 Revolution, large numbers of whom settled in the USA.”21

After the revolution, expression of anti-semitism was made a criminal offence. Indeed, “Jewish intellectuals and workers were disproportionately active in the revolutionary movement in the Russian Empire. In 1922, Jews represented 5.2% of Communist Party membership (about five times their percentage of the population).”

Soviet newspapers gave significant attention to the plight of black people in the US. Many prominent African-Americans visited the Soviet Union and were moved to comment on how much better they were treated there than in the country of their birth. The legendary African-American civil rights activist and Pan-African, W. E. B. Du Bois, wrote that “the Soviet Union seems to me the only European country where people are not more or less taught and encouraged to despise and look down on some class, group or race. I know countries where race and colour prejudice show only slight manifestations, but no white country where race and colour prejudice seems so absolutely absent. In Paris I attract some attention; in London I meet elaborate blankness; anywhere in America I get anything from complete ignoring to curiosity, and often insult. In Moscow, I pass unheeded. Russians quite naturally ask me information; women sit beside me quite confidently and unconsciously. Children are uniformly courteous.”22

The emancipation of women

In the course of two years, Soviet power in one of the most backward countries of Europe did more to emancipate women and to make their status equal to that of the “strong” sex than all the advanced, enlightened, “democratic” republics of the world did in the course of 130 years.23

The Soviet Union was for many decades the world leader in developing women’s rights. Article 122 of the 1936 constitution established not only the principle of gender equality but the means by which the state would facilitate it: “Women in the USSR are accorded equal rights with men in all spheres of economic, state, cultural, social and political life. The possibility of exercising these rights is ensured to women by granting them an equal right with men to work, payment for work, rest and leisure, social insurance and education, and by state protection of the interests of mother and child, pre-maternity and maternity leave with full pay, and the provision of a wide network of maternity homes, nurseries and kindergartens.”

Family law was written to create a context for a flourishing of women’s rights. Subsidised childcare was made universal, with the result that, by the late 1970s, the percentage of women in work was 83% – compared with 55% in the US – and over 40% of professional scientists were female. Szymanski writes that “in 1970, there were more women physicians in the USSR than throughout the rest of the world, with about 20 times more than in the US.” He concludes that “women are considerably more independent of men, and far greater opportunities are open to them than ever before, or that exist for women in comparable capitalist countries.”24 These are remarkable achievements, particularly in view of the patriarchal backwardness of the Russian Empire under the tsars.

Supporting the global struggle against colonialism and imperialism

In comparing the progress made in the Soviet Union between 1917 and 1991 with the progress made in the capitalist world in the same period, it’s crucial to bear in mind that capitalist progress was built on a bedrock of colonialism and imperialism. Industrialisation and modernisation in Britain would not have taken place without the grand-scale theft of productive land in the Americas, the transatlantic slave trade, and the colonial subjugation of India, Ireland and much of Africa. US-led economic progress in the 20th century rested on the profits of neocolonial exploitation of the larger part of the globe. Not only was Soviet progress more impressive in absolute terms, but it was many times more impressive for having been achieved without recourse to imperialism. Yegor Ligachev (Gorbachev’s deputy in the mid-1980s, deposed because he didn’t want to get rid of socialism) observes:

It should be kept in mind that everything we achieved was the result of our own efforts, whereas the developed capitalist countries accumulated much of their wealth by the open plunder of colonial peoples in the past and by ferrying cheap natural resources out of Third World countries today, exploiting their cheap workforce. In this way the capitalist countries have secured a relatively high standard of living for their populations.25

More than the Soviet Union not engaging in imperialist exploitation; it engaged in the opposite of imperialist exploitation, seeing itself as a key engine of the global anti-colonial and anti-imperialist movement – an all-weather friend to the oppressed and struggling peoples of Asia, Africa and Latin America. This position wasn’t taken purely out of goodwill and socialist morality but also as a means of developing the broadest possible unity against imperialism. In Lenin’s words: “[The European working class] will not be victorious without the aid of the working people of all the oppressed colonial nations, first and foremost, of Eastern nations.”26

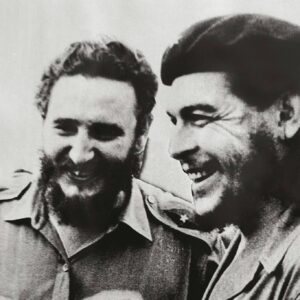

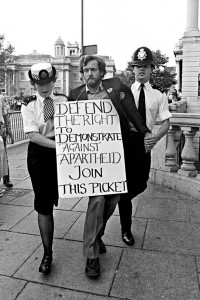

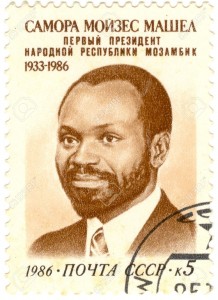

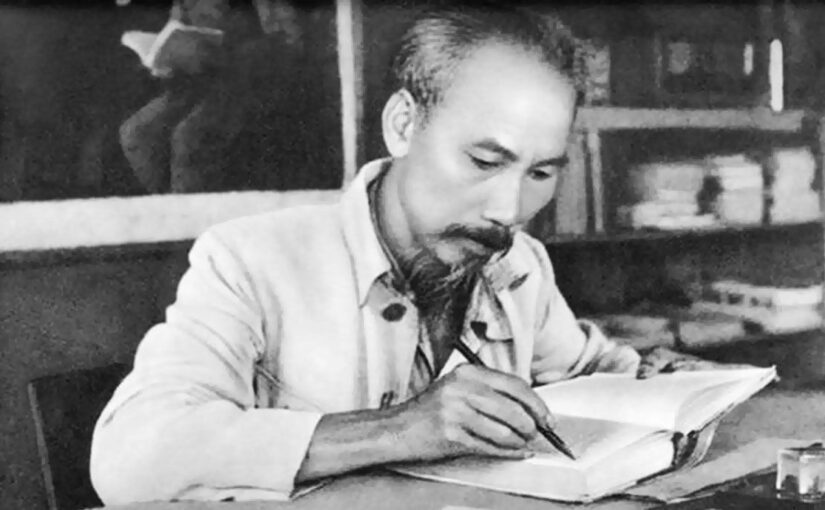

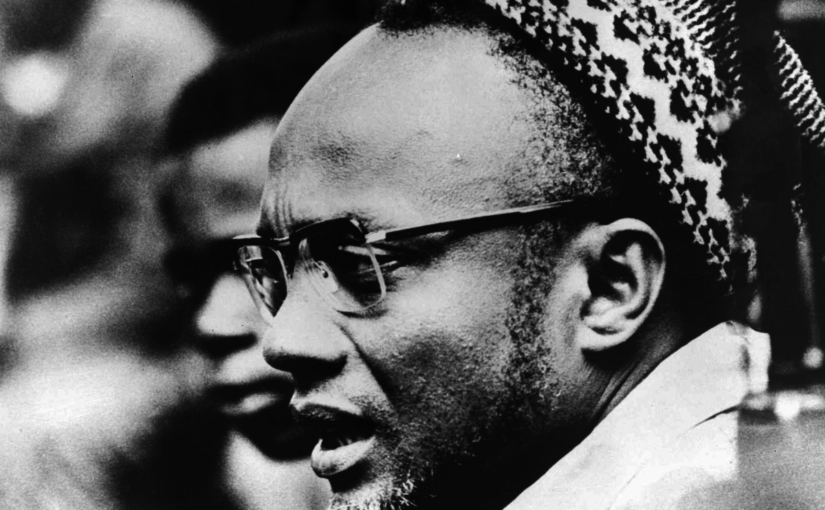

The Soviet Union made significant sacrifices in order to support liberation movements (including the ANC in South Africa, the MPLA in Angola, PAIGC in Guinea-Bissau, Frelimo in Mozambique) and progressive states (including the people’s democracies of central and eastern Europe, Cuba, Vietnam, Korea, Mongolia, Afghanistan, Angola, Mozambique, Mali, Guinea, Ghana, Ethiopia, India, Egypt, Libya, Grenada, Nicaragua, Indonesia, and more). This support was not simply tokenistic; indeed in many cases – including the historic victory of the Vietnamese patriotic forces – it was decisive. Fidel Castro went so far as to say that, “without the existence of the Soviet Union, Cuba’s socialist revolution would have been impossible… This means that without the existence of the Soviet Union, the imperialists would have strangled any national-liberation revolution in Latin America… Had the Soviet Union not existed, the imperialists would not even have had to resort to weapons. They would have strangled such a revolution with hunger. They would have liquidated it by only an economic blockade. But because the Soviet Union exists, it proved impossible to liquidate our revolution.”27

The Soviet Union served as a key support base for the other projects of socialist transformation in the 20th century, including the Chinese Revolution, which over the course of the last eight decades has comprehensively rejuvenated the Chinese nation, putting an end to feudal backwardness and colonial domination and making China a great world power. As Mao Zedong himself said, soon after the victory of the revolution: “If the Soviet Union did not exist, if there were no victory of the Anti-Fascist Second World War and no defeat of Japanese imperialism, … if there were no sum-total of these things, could we have won victory? Obviously not. It would also be impossible to consolidate the victory when it was won.”28

Paul Robeson remembered the USSR’s principled support for Ethiopia against Mussolini’s Italy, and for the native population of South Africa against the white supremacist government, concluding that “the Soviet Union is the friend of the African and the West Indian peoples”.29

A step forward in history

After the Paris Commune of 1871, which lasted only two months, the October Revolution was the world’s first attempt to build a socialist society, to put an end to the brutality, inequality and inefficiency of capitalism. As such, October “dispelled the myth of capitalism’s immutability as a ‘natural order of things’. It demonstrated that capitalism was not eternal and its replacement by socialism was on the agenda of history.”30

In its 74-year existence, the Soviet Union succeeded in creating a completely different type of society: one that deeply valued equality, shared prosperity, social justice, solidarity, culture and education. It made greater economic, social, scientific and cultural progress than its competitors in the capitalist world during the period of its existence. And this was done in spite of the extraordinary human and economic losses it sustained defending itself against foreign aggression (in the ‘civil war’ of 1918-21 and the German invasion/occupation of the Soviet Union, 1941-44). Gennady Zyuganov, veteran Russian communist and current leader of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, notes with justifiable pride:

The socialism that was built in the USSR and a number of other countries was, of course, far from perfect. But it exhibited some historic achievements. The socialist system enabled us to create a powerful state with a developed national economy. We were the first to venture into the cosmos. Our culture reached unprecedented heights. We were justly proud of our achievements in science, theatre, film, education, music, ballet, literature, and the visual arts. Much was done to develop physical culture, sports, and folk arts. Every citizen of the USSR had the right to work, free education and medical care, and a secure childhood and old age. Appropriate budgetary allocations subsidised housing and provided for the needs of children. People were sure of their tomorrow. A workable alternative to capitalism was created in our own country and in other socialist countries… And these changes were made in the shortest period recorded in world history for such a transformation.31

Like any country, the Soviet Union suffered its fair share of complex problems and was guilty of its fair share of mistakes, but by no reasonable measure can the Soviet period be deemed a failure. The ‘failed experiment’ hypothesis of the Soviet collapse is merely an extension of old-fashioned Cold War propaganda. In the next article, I will explore the economic stagnation that appeared in the early 1970s, and will discuss how this fed into a sense of disillusionment that contributed to the weakening of the socialist project.

-

David Kotz and Fred Weir, Revolution From Above – The Demise of the Soviet System, Routledge, 1997 ↩

-

Roger Keeran and Thomas Kenny, Socialism Betrayed – Behind the collapse of the Soviet Union, International Publishers, 2004 ↩

-

Vijay Prashad (editor), Red October – The Russian Revolution and the Communist Horizon, LeftWord Books, 2017 ↩

-

Michael Parenti, Blackshirts and Reds, City Lights Publishers, 2001 ↩

-

Paris Review: Chinua Achebe, The Art of Fiction No. 139, 1994 ↩

-

See for example Daily Mail: Key Corbyn ally who helped run election campaign is speaking at event to celebrate the Russian Revolution, 2017 ↩

-

Yuri Andropov, Report on 60th anniversary of the USSR, 21 December 1982 ↩

-

Blackshirts and Reds, op cit ↩

-

Boris Ponomarev, Marxism-Leninism in Today’s World, Pergamon Press, 1983 ↩

-

Lenin: Meeting Of The Petrograd Soviet Of

Workers’ And Soldiers’ Deputies, 1917 ↩ -

Albert Szymanski: Human Rights in the Soviet Union, Zed Books, 1984 ↩

-

Parenti, op cit ↩

-

Brookings: Long-term Unemployment Is #1 Social and Economic Problem in America, 2014 ↩

-

Hewlett Johnson: The Socialist Sixth of the World, Victor Gollancz, 1939 ↩

-

Keeran and Kenny, op cit ↩

-

Lenin: The Right of Nations to Self-Determination, 1914 ↩

-

Marx: Confidential Communication on Bakunin, 1870 ↩

-

Samir Amin: Saving the Unity of Great Britain, Breaking the Unity of Greater Russia, 2014 ↩

-

Szymanski, op cit ↩

-

ibid ↩

-

Szymanski, op cit ↩

-

Cited in William Mandel, Soviet But Not Russian: The ‘Other’ Peoples of the Soviet Union, Ramparts Press, 1985 ↩

-

Lenin: Soviet Power and the Status of Women, 1919 ↩

-

Szymanski, op cit ↩

-

Inside Gorbachev’s Kremlin: The Memoirs Of Yegor Ligachev, Westview Press, 1996 ↩

-

Lenin: Address to the Second All-Russia Congress of Communist Organisations of the East, 1919 ↩

-

Fidel Castro: Speech at Red Square, 1963 ↩

-

Cited in Li Lisan: The Chinese Labour Movement, 1950 ↩

-

Philip S Foner, Paul Robeson Speaks: Writings, Speeches, Interviews, 1918-74, Kensington Publishing Corp, 1998 ↩

-

Ponomarev, op cit ↩

-

My Russia: The Political Autobiography of Gennady Zyuganov, Routledge, 1997 ↩