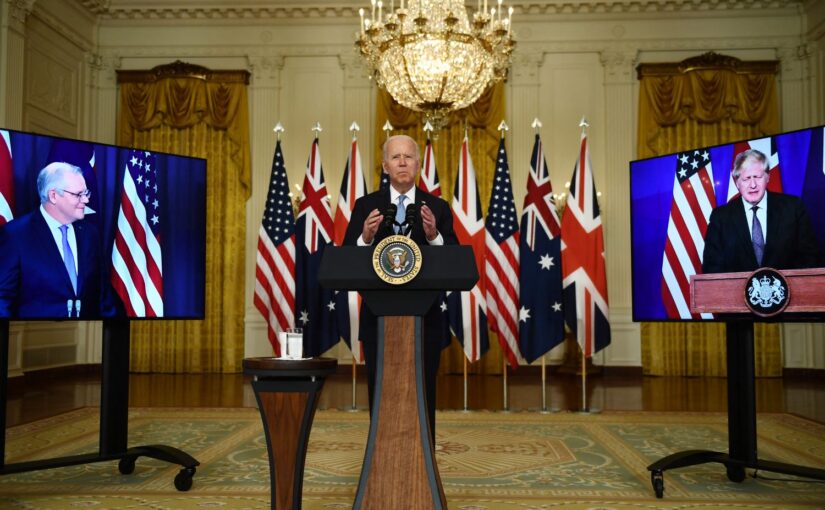

Invent the Future editor Carlos Martinez was interviewed by Sean Blackmon and Jacquie Luqman on the Sputnik Radio show By Any Means Necessary on 17 September 2021. We discuss the recently-announced alliance between the US, Britain and Australia, and its clear purpose of advancing the war drive against China. Along with this, we talk about the historical imperialist and colonialist interests of the three countries, how the supplying of nuclear submarines to Australia raises the threat of nuclear confrontation, and the anti-China industry manufacturing consent for hostility against China.

Escucha”US Continues War Drive Against China With AUKUS Alliance” en Spreaker.Tag: britain

Socialists should oppose the new cold war against China – a reply to Paul Mason

This article originally appeared in the Morning Star.

Living in the heartlands of imperialism, you learn to expect censure if you defend socialism and oppose war. To be attacked by the forces of the hard right is nothing unusual; as Sekou Toure observed, “if the enemy is not doing anything against you, you are not doing anything.” Hence getting trolled by Donald Trump Jr for example can comfortably be worn as a badge of honour.

To be attacked by a stalwart of the left, someone who had been a prominent supporter of Jeremy Corbyn, is of course less welcome. In a recent piece for the New Statesman, Paul Mason singles out the Morning Star and Socialist Action as being “the two left-wing publications in the UK that appear committed to whitewashing China’s authoritarian form of capitalism”, highlighting articles by myself, the Morning Star editor and John Ross.

Uncritical parroting of Cold War propaganda

Mason’s key complaint against the anti-imperialist left is that it “parrots the Chinese state”, for example by labelling the Hong Kong protestors as a “violent fringe”. It’s ironic then that, in his critique, he prefers to parrot the China hawks in Washington – the likes of Donald Trump, Mike Pompeo, John Bolton and Peter Navarro.

Mason states for example that the Chinese state is “using forced labour, sexual violence, coercive ‘re-education’ and mass incarceration” to destroy Uyghur culture. The evidentiary basis for this narrative, which has now become hegemonic in the West, is laughably weak, on a par with the claim that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction, or that Muammar Gaddafi was using rape as a weapon of war.

These are perhaps sore points, since Mason supported the bombing of Libya and as recently as 2017 put forward the view that Iraq was ‘bluffing’ about having WMD, implying that the Iraq War was built on faulty intelligence – rather than being a knowing and callous act of imperialist domination.

The allegations regarding Chinese mistreatment of Xinjiang’s Uyghur population have been comprehensively debunked by Ajit Singh and Max Blumenthal, and there’s no need to recapitulate their work here. What’s worth noting however is the depressing familiarity of how the ‘Uyghur genocide’ story has become so widespread: separatist extremist group (in this case the World Uyghur Congress) forms an alliance with Washington-based NGO (in this case the Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders), which uses US tax-payer money – via the National Endowment for Democracy – to create a slick PR campaign building mass support for a broad-based attack on an ‘enemy state’ (in this case China).

It was a very similar process that won significant support within the Western left for NATO’s wars in Yugoslavia, Libya and Syria. Interestingly, the two publications Mason cites in his recent attack – the Morning Star and Socialist Action – were among the honourable few that weren’t duped by this propaganda. Paul Mason on the other hand cannot make such a claim. Indeed his major criticism of the Western powers over Libya and Syria is the ‘powerlessness’ of their regime change operations.

By accusing others of “parroting the Chinese state”, Mason is simply trying to divert attention from his own record of parroting State Department talking points that serve specifically to build public support for wars (of both the hot and cold variety).

This isn’t taking a principled and consistent stance against injustice; it’s feeding into a dangerous propaganda campaign that’s combined with economic sanctions, naval patrols in the South China Sea, the construction of military bases, a strategy of ‘China encirclement’, diplomatic attacks, support for violent separatist movements, and an economic and political ‘delinking’ that threatens to demolish global cooperation around some of the crucial issues of our time, including climate change and pandemic containment.

Neither Washington nor Beijing?

Mason informs his readers that “the point of being a socialist is being able to walk and chew gum at the same time.” This isn’t an idea that I’ve come across in the writings of Marx, Engels or Lenin, but presumably it’s buried somewhere in the Grundrisse. Anyway, Mason’s point is that a good leftist can condemn both the US and China; that one should adopt a position of Neither Washington nor Beijing. This position – which appears to be gaining traction in parts of the left – was absurd in its original Neither Washington nor Moscow form, and it’s absurd now.

To put an equals sign between the US and China, to portray their relationship as a rivalry between imperialist blocs, is to completely misunderstand the most important question in global politics today.

The baseline foreign policy position of the US is to maintain its hegemony; to consolidate a system of international relations (economic, diplomatic, cultural and military) that benefits the US ruling class. This has its clearest expression in the wars, sanctions and destabilisation campaigns it wages, with devastating consequences, in Iraq, Libya, Syria, Afghanistan, Iran, Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, Zimbabwe and elsewhere.

China on the other hand strongly promotes peaceful cooperation and competition; it consistently opposes war; and it pushes a multipolar model of international relations – “a pattern of multiple centres of power, all with a certain capacity to influence world affairs, shaping a negotiated order” (Jenny Clegg, China’s Global Strategy).

In the words of Hugo Chávez: ”China is large but it’s not an empire. China doesn’t trample on anyone, it hasn’t invaded anyone, it doesn’t go around dropping bombs on anyone.” Equating the US and China means failing to stand up to a Cold War which is being waged specifically by the US and its allies. The target of this war is not just China but the whole concept of a democratic world order. As such, Neither Washington nor Beijing is better understood as Neither imperialism nor anti-imperialism.

The point of being a socialist

If there’s a “point to being a socialist”, it’s to work for the maximum extension of human rights to all people. Foremost among those rights are the right to life, to peace, to education, to healthcare, to freedom from poverty, to freedom from discrimination. A socialist surely believes that all people should be able to access a dignified, fulfilling, healthy and interesting life.

China has made rather impressive progress in that direction, having lifted over 800 million people out of poverty in the last few decades. At the time of the declaration of the People’s Republic in 1949, after a century of imperialist domination and civil war, China was one of the poorest countries in the world, with an average life expectancy of just over 30 and a pitifully low level of human development. Currently China’s life expectancy is 77 years and its literacy rate 100 percent. All Chinese have access to healthcare, education and modern energy. This is, without any exaggeration, the most remarkable campaign against poverty and for human rights in history.

The late Egyptian political theorist Samir Amin, who knew something of the conditions of life in the Third World, wrote of China’s successes in poverty alleviation: “No one in good faith who has travelled thousands of miles through the rich and poor regions of China, and visited many of its large cities, can fail to admit that he never encountered there anything as shaming as the unavoidable sights in the countryside and shantytowns of the third world.” (Beyond US Hegemony: Assessing the Prospects for a Multipolar World)

And yet, a prominent British leftist like Paul Mason can casually reduce the nature of the Chinese state to “China’s capitalist billionaire torturers” and “the brutal authoritarianism of the CCP.” Quite frankly, if you acknowledge China’s successes improving the lives of hundreds of millions of people but you think it’s “brutal vulture capitalism”, then perhaps you have to stop calling yourself a leftist and accept that brutal vulture capitalism is better than you thought!

Oppose imperialism and McCarthyism

The fundamental problem with Paul Mason is that, in the final analysis, he stands on the side of imperialism. Even his support for the Left Labour project – now quickly dropped in the era of Starmer – existed within a pro-imperialist framework, rejecting Corbyn’s anti-war internationalism and pushing support for NATO and Trident renewal.

Washington is currently leading the way towards a New Cold War that poses a potentially existential threat to humanity. This New Cold War is accompanied by a New McCarthyism which seeks to denigrate and isolate those people and movements that work for peace and multipolarity. In joining in with – and giving a left veneer to – this witch-hunt, Paul Mason provides proof once again that he doesn’t have any useful role to play in paving the long road to socialism.

Labour should not be parroting Trump’s anti-China Cold War rhetoric

This article originally appeared in the Morning Star

There’s been a worrying upsurge in anti-China propaganda on both sides of the Atlantic. While imperialist hostility towards China’s rise has become an intrinsic characteristic of the current era – particularly since the launch of the ‘Pivot to Asia’ by the Obama administration in 2011 – the rhetoric has become increasingly hysterical and absurd over the last few months.

There are currently four main lines of attack being pushed on a daily basis by the US and British ruling classes:

- The newly-introduced National Security Law is an attack on the basic freedoms of the people of Hong Kong and violates China’s legal obligations under the Sino-British joint declaration of 1984.

- The Uyghur population of Xinjiang is being repressed in any number of indescribably brutal ways, including through mass incarceration in ‘re-education camps’ and forced sterilisation.

- China – as a result of its secrecy, incompetence, vindictiveness, or some combination thereof – didn’t give the world sufficient warning of the Covid-19 outbreak and must therefore bear responsibility for the havoc being wreaked by the pandemic.

- China’s technology companies are providing, or seek to provide, secret information to the Chinese state, and therefore their involvement in Western economies should be actively restricted.

Unsurprisingly, it’s the US government leading the charge. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo accuses China of having “broken multiple international commitments including those to the WHO, the WTO, the United Nations and the people of Hong Kong”. He rails against China’s “predatory economic practices, such as trying to force nations to do business with Huawei, an arm of the Chinese Communist Party’s surveillance state.”

This is a bi-partisan position in the US, sadly. Democratic presidential contender Joe Biden is keen to prove he’s also every bit the China hawk, threatening sanctions and promoting a zany and totally unfounded smear about the forced sterilisation of Uyghur women. Even progressive congresswomen Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib have joined in with this mindless China-bashing.

In both the US and Britain, relations with China are at their lowest point for decades. It’s no surprise that the Boris Johnson government, instinctively Atlanticist and desperately pursuing a post-Brexit trade agreement with the US at almost any cost, is largely parroting Trump’s line.

Having agreed in January to Huawei having a role in the development of Britain’s 5G infrastructure, the government is now considering dropping Huawei so as not to be “vulnerable to a high-risk state vendor”. Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab has stated there’ll be “no return to business as usual” in Britain’s relations with China. Meanwhile, leading government officials have been vocal in their criticism of Hong Kong’s new National Security Law, going so far as to offer some three million Hong Kong residents the opportunity to settle in Britain and apply for citizenship.

Those of us who stand for peace and for mutually beneficial cooperation between Britain and China might hope that the Labour Party would provide some meaningful opposition to the government’s reckless behaviour. Unfortunately the indications thus far are that Labour is enthusiastically climbing aboard the New Cold War bandwagon.

Shadow foreign secretary Lisa Nandy has been actively promoting anti-China propaganda and pushing the Tories to take a harder stance against China, for example urging that action be taken against British businesses that are “complicit in the repression” in Hong Kong (ie that don’t actively support the riots).

While Nandy’s words might bring disappointment to socialists, progressives and peace activists, they were at least welcome in certain quarters: notorious right-wing blogger Guido Fawkes celebrated the “welcome change in Labour Party policy – standing up to, rather than cosying up to despotic regimes.”

Nandy’s position is however positively nuanced in comparison to that of Stephen Kinnock, Shadow Minister for Asia and the Pacific, who accuses China of promoting its “model of responsive authoritarian government” worldwide. Kinnock describes the ‘golden era’ of Sino-British relations, inaugurated during the Cameron government, as being an “abject failure” in which Britain had “rolled out the red carpet for China and got very very little in return”.

It therefore seems that the Labour leadership in its current incarnation is moving towards unambiguous support for the US-led New Cold War on China. It’s particularly demoralising that, with a few honourable exceptions, most notably Diane Abbott, the Labour left isn’t currently putting up any serious resistance to this dangerous trajectory.

While very few Labour MPs have spoken of the dangers of a New Cold War, John McDonnell has recorded a histrionic (and hopelessly one-sided) denunciation of the Chinese state’s alleged mistreatment of the Uyghur Muslims. Apsana Begum has repeated these tropes in parliament, claiming that when the Chinese government celebrates its successful suppression of the East Turkestan Islamic Movement’s murderous bombing campaign, its “definition of terrorism is troublingly vague”. The usually-excellent Claudia Webbe has called on the government to “oppose state-sanctioned violence” in Hong Kong, choosing to ignore the United States-sanctioned violence of separatist protestors.

This is all frankly disastrous and worrying. The US administration is leading a very serious escalation of the New Cold War, trying to isolate China, trying to demonise it, trying to undermine it and to prevent its economic rise. The propaganda ‘soft war’ with regard to Hong Kong, Xinjiang and Covid-19 is combined with moves towards economic ‘decoupling’ along with ‘hard war’ encirclement measures, including ramped up and provocative patrols in the South China Sea.

A New Cold War will bring no benefit whatsoever to ordinary British people. It will mean fewer jobs, reduced investment, reduced export markets and increased prices on imports. All this will be accompanied by rising anti-Asian racism and a renewed momentum along the ideological dead-end of empire nostalgia. Even the relatively more sane representatives of the ruling class such as Jeffrey Sachs recognise the danger of this wave of sinophobia “spiralling into greater controversy and greater danger”, resulting in a US-China Cold War that’s “a bigger global threat than the coronavirus.”

What British people need to do, in the interests of peace and progress, is to push for respectful, friendly and mutually beneficial relations with China. Opposing the New Cold War must become a key priority for the labour and anti-war movements.

Activists in Britain and the US are organising an international online meeting against the New Cold War, to take place on Saturday 25 July at 2pm BST. Speakers include Medea Benjamin, Vijay Prashad, Qiao Collective, Wang Wen, Jenny Clegg and Kate Hudson. More info at www.nocoldwar.org

Book review: John Lister – Unhealthy Profits: PFI in the NHS, its real costs and consequences

This article first appeared in the Morning Star on 25 March 2019.

John Lister’s well-written and scrupulously researched book is a crucial weapon in the defence of the NHS.

It advances a rigorous explanation of the economic theory behind the private finance initiative (PFI), its putative benefits and the reality of its implementation in the NHS over the last quarter-century, drawing on the specific experience of the Pinderfields and Pontefract hospitals in Yorkshire built as part of a £311 million deal with the Royal Bank of Scotland.

Championed by Tory chancellor Norman Lamont, the concept of PFI originally surfaced in the early 1990s but it wasn’t until the New Labour victory of 1997 that PFI went from being one of many funding models to being the only game in town.

“PFI had an irresistible attraction for New Labour ministers keen to boast of the new hospitals that were being built [and for] NHS trust bosses snatching at the lure of private funding at a time when public provision of capital investment in the NHS had been deliberately reduced,” Lister writes.

Superficially, PFI seemed like a great idea. It meant that new hospitals could be built without the Treasury having to pay for them up front, with private consortiums doing the borrowing, building the hospitals and then making their money back over a 25 to 40-year period through monthly fees paid by the relevant NHS trust.

Thus vast infrastructure spending was kept off the Treasury’s books and private-sector partners could absorb all the risk. It was an idea that fitted perfectly with the prevailing neoliberal economic orthodoxy.

Of course, massive inefficiencies are built into the very fabric of PFI. Private-sector borrowing is much more expensive than its public-sector counterpart and, where new hospitals were needed, the money could’ve been borrowed by the government at a far lower rate of interest than that paid to PFI financiers.

More significantly, PFI consortiums are private companies with a primary responsibility to their shareholders, whose handsome dividends can only be funded by overcharging their customers —the NHS.

Lister shows all too clearly that in practice PFI has been comprehensively disastrous for the NHS. Once hospitals have been built and are being leased back to NHS trusts, the overall cost over the lifetime of a PFI is typically three to four times the capital value — not a good mortgage deal by any standard.

Beyond the cost of the buildings themselves, NHS trusts are also tied into inflated maintenance costs, whereby PFI consortiums enjoy an exclusive contract to provide — invariably bad — food, change lightbulbs and impose penalty charges on people parking in A&E.

The bloated monthly payments have left many NHS trusts on the verge of bankruptcy. Ironically, a number of trusts have had to be bailed out by the Treasury, thereby voiding the one supposed benefit of using a PFI in the first place.

Other trusts have been forced to make shameful decisions on staff and service provision. Bed numbers have gone down in nearly every PFI hospital and there is constant pressure to cut back on staff numbers and conditions. Increasingly, agency staff are preferred so as to avoid paying negotiated rates.

Lister notes that British Medical Association research shows that not only did the PFI process result in an average 32 per cent loss of beds but during the planning process the costs of the PFI schemes escalate by a “staggering average”of 72 per cent.

After cutting staff and beds, the only remaining means to raise the money to pay PFI costs is often to sell NHS land and buildings to the PFI consortiums, thereby continuing the transfer of public assets into public hands. And these are not just any private hands but usually off-shore finance capitalists that go to great lengths to avoid paying tax.

HSBC Infrastructure Company Limited, incorporated in the tax haven of Guernsey, has over 100 investments in health, education and transport valued at more than £1.8 billion.

Lister also offers a neat solution to the PFI rip-off — nationalising the special purpose vehicles that run them. Any compensation and changes to the monthly payments would be determined by an Act of Parliament and not subject to complex and expensive legal wrangling.

“After more than 25 years of PFI schemes in Britain, it’s high time this relatively straightforward, neat, legal and affordable policy was explicitly adopted by the Labour Party as the government in waiting and endorsed by the unions whose members have been exploited by PFI contractors and consortia,” Lister concludes.

Brexit is an attack on the working class

This post was updated on 7 April to reflect the updated situation and to include some discussion on the impact of Brexit on Ireland.

The date set for the United Kingdom to leave the European Union, 29 March 2019, is now in the past. The Brexit deadline has been extended, and is likely to be extended again. MPs can’t agree on what a deal should look like, only that the deal presented by the government isn’t very good. Labour and the Tories are in negotiations with a view to finding common ground on a softer Brexit, but at the time of writing we still don’t have much clue what the outcome will be. Will Theresa May finally be able to get her deal through parliament? Might we leave with a ‘Norway-plus’ type of arrangement, retaining membership of the Customs Union and potentially the Single Market? Might we leave without a deal, leading to probable economic crisis and social chaos? Or could there be a lengthy postponement, or could the whole thing be cancelled?

Absurdly, much of this uncertainty comes down to seemingly insurmountable divisions within the Conservative Party, and to the government’s prioritisation of its own petty interests over those of the British people – not to mention a desperation on the part of the British ruling class to keep Jeremy Corbyn as far as possible from 10 Downing Street.

Of course, those of us on the left can’t control what ruthless Tory Brexiters do. What we can and should do is develop a reasonable, coherent strategy of our own; a strategy with the power to unite a wide array of forces with the critical mass to defeat the anti-democratic and anti-popular machinations of the Tories and their chums on the extreme right. In so doing, we can avert disaster and strengthen the position of the working class.

A united strategy needs to be based on a detailed and realistic understanding of what Brexit is and what class forces it represents. As it stands, this understanding is largely absent. The ‘remain’ side of the debate has been dominated by liberal/centrist voices, including the likes of Tony Blair, Chuka Umunna and others trying to leverage the political crisis to weaken Corbyn. The bulk of the non-Labour left – including the Communist Party of Britain, the Socialist Party, Counterfire, the Socialist Workers Party – has been promoting a ‘Lexit’ line based on a combination of misunderstanding and wishful thinking, and in some cases with a dose of chauvinism. Even within the Labour left and the trade unions, there’s a reluctance to really articulate a coherent progressive vision (or systematic opposition to Tory Brexit) owing to worries about alienating people in pro-Brexit Labour-voting constituencies.

Without this understanding and the strategy that flows from it, we’re sleepwalking into a nightmare that will strengthen the most reactionary elements of the ruling class and that could set back progressive forces for a generation.

This article will attempt to show that the Brexit project serves the interests of a tiny finance-capitalist elite; that it represents an attack on working class conditions and unity; that it strengthens rather than weakens imperialism; that it will lead to greater inequality and poverty; that it is, in fact, a neoliberal scam that could have a devastating impact on the poorer sections of British society.

Neoliberalism on steroids

From the point of view of the millionaires who funded the leave campaign, the purpose of Brexit is to allow business to escape the public protections the EU provides. (George Monbiot)

Millions of people voted for Brexit. Their motivations were many and complex – including an amorphous idea of “taking back control”, old-fashioned xenophobia and anti-immigrant scapegoating, as well as a healthy middle finger to the smug status quo so amply represented by then-prime minister David Cameron. Very few of them voted for neoliberalism or deepening austerity; very few thought that the important thing was to reduce restrictions on big business such that it can exploit more ruthlessly and generate ever more fabulous profits. As Fintan O’Toole points out: “for most of those who voted for it, Brexit means a ‘return to the nation state’. But for many of those behind it, there is a very different ideal. They use this language because it is the only one that is politically viable. But for them the exit from the EU is really a prelude to the exit from the nation state into a world where the rich are truly free because they are truly stateless” (Heroic Failure: Brexit and the Politics of Pain, Apollo, 2019).

For many left-wing supporters of Brexit, the whole point is to break with neoliberalism, not strengthen it. They see the EU as the standard-bearer of free-market fundamentalism in the present era, forgetting that, within Europe, Britain was the first country to enthusiastically venture into the brave new world of massive deregulation. In the early 1980s, it was Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and Bob Hawke that led the neoliberal charge. Indeed, it took quite a long time to convince continental Europeans to pick up the baton. While Britain participated in the process of European integration through the development of the European Economic Community (EEC) and then the EU, this participation was always reluctant and partial, precisely because of British capital’s distrust for the relatively softer, more regulated version of capitalism pursued on the continent. Nothing could reconcile Thatcher and her friends to the concept of a “platform of guaranteed social rights”.

Even today, after a quarter of a century of deepening alignment with the new economic orthodoxy, France and Germany are far less ‘business-friendly’ environments than Britain (both charge around 30 percent corporation tax, for example). While the UK ranks 7th globally in the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, Germany ranks 24th and France 71st.

The EU mandates a level of protection for workers, it restricts off-shoring and tax avoidance, and it attempts to regulate the activities of the big banks. When the EU proposed a ‘Tobin tax’ on financial transactions in 2013, it was the British government that led the opposition to anything that limited the profits of the mega-rich. Boris Johnson, then London’s mayor, was viciously opposed to any increase in the EU’s regulatory reach: “We cannot allow jobs, growth and livelihoods to be jeopardised by those in the EU who mistakenly view financial services as an easy target.”

Jeremy Corbyn was 100 percent correct when he pointed out that “people in this country face many problems, from insecure jobs, low pay and unaffordable housing to stagnating living standards, environmental degradation, and the responsibility for them lies in 10 Downing Street, not in Brussels.”

‘Taking back control’ doesn’t mean assigning any new powers to the ordinary people of Britain. It means reducing EU regulations on British business. The idea isn’t even to reassign these powers to Whitehall but to get rid of them altogether. In a world where multinational corporations and financial institutions are too big to be subjected to any meaningful pressure by national governments like the UK, freeing themselves from supranational regulatory bodies like the EU means freeing themselves from oversight. It’s not just ‘small government’, it’s no government.

Few have articulated this fundamentalist Thatcherite vision more clearly than Nigel Lawson, former Chancellor of the Exchequer and president of the fanatically pro-Brexit ‘Conservatives for Britain’ pressure group. Writing in the Financial Times in September 2016, he complains bitterly that while “the Thatcher government of the 1980s transformed the British economy … through a thoroughgoing programme of supply side reform, of which judicious deregulation was a critically important part”, this process was limited by the “growing corpus of EU regulation”. Now, however, “Brexit gives us the opportunity to address this; to make the UK the most dynamic and freest country in the whole of Europe: in a word, to finish the job that Margaret Thatcher started”.

The Brexit engineers are involved in the construction of a Thatcherite neoliberal paradise that will bring fabulous profits to a few capitalist buccaneers, and ever-increasing misery to those at the bottom of society.

A boost for the Atlanticists

Brexit was not, to my mind at least, a choice between the EU and ‘independence’, but a choice between staying part of a flawed union or choosing to deepen ties with the American Empire and continue the ‘Americanisation’ of the British economy. If Britons wish to learn what a US-style healthcare service looks like, they are free to talk to any poor American (Akala, Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire, Two Roads, 2018).

There’s a widespread assumption that the British ruling class is overwhelmingly opposed to Brexit. This is not the case; the ruling class is deeply divided on Brexit. The line of division is essentially between a relatively European-aligned section of British capitalism and a relatively US-aligned ‘Atlanticist’ section. This reflects deeper economic and strategic divisions: the Atlanticist ruling class is more connected to finance capital, to the military-industrial complex, and to Big Oil; its political orientation is closer to an openly aggressive, racist Trump-ism than to the relatively more sophisticated approach of Obama or Merkel. The last time this division was manifested so starkly was in 2003, when the British ruling class was split as to whether to join the US war on Iraq or to support the French/German position against the war.

The leading pro-Brexit politicians – Boris Johnson, Michael Gove, Nigel Farage, Jacob Rees-Mogg, David Davis, Liam Fox, Dominic Raab, Iain Duncan Smith and Steve Baker – are all noted Atlanticists. Liam Fox for example has consistently maintained a pro-US orientation, including strongly favouring close military alliance. His charity, Atlantic Bridge, exists to promote close coordination between the Conservative Party and the hard-right Tea Party nutcases in the Republican Party. Boris Johnson is a wholehearted supporter of Making America Great Again, close with both Donald Trump and Steve Bannon. Trump, Bannon and John Bolton are all fond supporters of the Brexit project, as is Rupert Murdoch. The multi-millionaire financiers of the Brexit campaign – people like Arron Banks, Peter Hargreaves, Peter Cruddas, Stuart Wheeler, Michael Hintze, Martin Bellamy, Jon Moynihan and Robert Hiscox – all favour closer links with the US. They are certainly not motivated by any overarching desire to weaken imperialism or empower the working class.

Brexit is a key component of Trump’s ‘America First’ strategy. It’s instructive that the Heritage Foundation, a highly influential neoliberal think-tank in the US and a major force in the Trump administration, has lobbied for Brexit over the course of over a decade on the basis that it will strengthen the US’ hand in the global economy and help to weaken the EU. British political analyst TJ Coles gives a helpful summary of Heritage’s changing attitude towards the EU: “The Heritage Foundation describes America’s initial interest in a United Europe as a bulwark against the Soviet Union… As there is now no Soviet Union, there is no need for a United Europe. A regulated European Union, which erects barriers to US products and services (such as labels identifying genetically-modified foods and regulations against privatisation) is bad for America’s corporate profits. After the financial crisis of 2008, Europe’s central command in Brussels started regulating financial markets in an effort to prevent another crash. The Heritage Foundation report analyses America’s efforts to use Britain as a ‘Trojan Horse’ to push through state deregulation in Europe. As Britain was not powerful enough to do this, America felt that a weakened Europe would better serve its financial and trade interests” (The Great Brexit Swindle, Clairview, 2016).

Leaving the EU Single Market, Britain will not suddenly become a major economic player in its own right; its economic strength and geographic location make that impossible. With the imposition of tariffs between Britain and its biggest trading partner, Britain will be forced to look elsewhere for a major trade deal. That means, first of all, a ‘free trade agreement’ with the US, the terms of which will be dictated by the latter. As Tom O’Leary writes, “the terms of negotiations between the UK and US will reflect the real relationship of forces between the two economies. The US economy is approximately 6.5 times greater than the UK economy… For the Trump negotiators, there are ten economies in the world whose GDP is greater than or more or less equal to that of the UK (on a PPP basis). It will be the UK which is desperate for a deal, not Trump… Any new deal is unlikely to compensate for the lost trade with the EU and will come at a significant price, in terms of workers’ rights, environmental protections, consumer safeguards and the privatisation of UK public services.”

Deepening division of the working class

It is sometimes easier to blame the EU, or worse to blame foreigners, than to face up to our own problems. At the head of which right now is a Conservative Government that is failing the people of Britain (Jeremy Corbyn, April 2016).

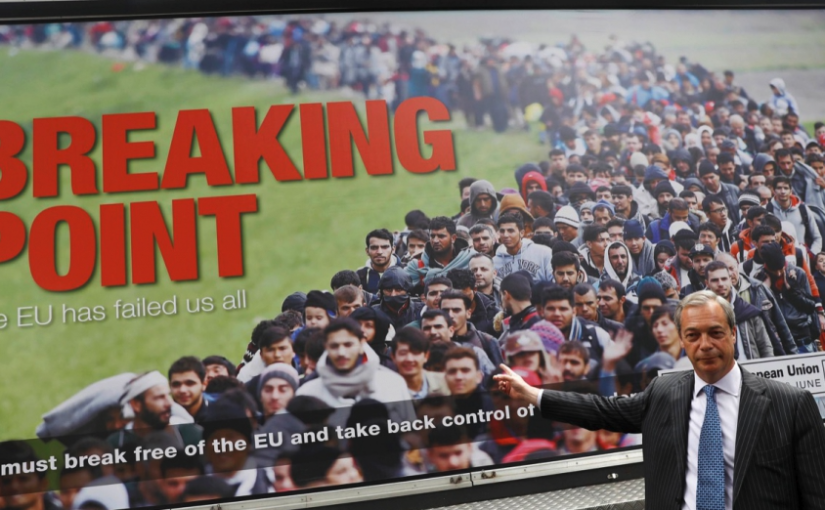

Polling has consistently shown that anti-immigration sentiment was the one of the key motivating factors in the Brexit referendum. A fairly typical study found that nearly three-quarters of Leave-voters were worried about immigration levels. Brexit campaigners shamelessly leveraged this latent xenophobia, with Nigel Farage’s infamous ‘breaking point’ poster being a particularly nasty example, along with Boris Johnson and Michael Gove repeatedly using Turkey’s aspiration of EU membership as a pro-Brexit scarecrow. As Aditya Chakrabortty pointed out, “One didn’t need especially keen hearing to pick that up as code for 80 million Muslims entering Christendom.”

This type of message was particularly effective, since it was essentially a reiteration of the racist language of the Tory mainstream. A study by Kings College London found that media coverage of immigration issues “more than tripled during the ten-week Brexit campaign, rising faster than any other political issue and appearing on 99 front pages, compared with 82 about the economy. Most of these front pages (79) were published by pro-leave newspapers.”

Although Theresa May campaigned (very half-heartedly) to remain in the EU, she didn’t feel strongly enough about it to counter anti-immigrant propaganda, instead choosing to suppress multiple studies showing that immigration doesn’t lead to lower wages. Plus of course she was the architect of the ‘go home’ vans, the hostile environment, and the chief culprit of the Windrush debacle. The Remain campaign was mainly defensive on the issue of immigration, choosing not to promote an anti-racist narrative. Of the prominent Remain supporters, it was only Jeremy Corbyn and his close circle in the shadow cabinet – along with the SNP, Greens and Plaid Cymru – that actively defended immigration. When they did so, they were either ignored or ridiculed by the press.

Fintan O’Toole writes that the Brexit vote “depended on an ostensibly improbable alliance between Sunderland and Gloucestershire, between hard old steel towns and rolling Cotswold hills, between people with tattooed arms and golf club buffers” (op cit). This unlikely convergence was mediated by decades of anti-immigrant rhetoric; of old-fashioned scapegoating that blamed immigrants for the problems of capitalism.

Survey data indicates that a significant majority of the British population would like immigration numbers to be reduced, presumably believing – incorrectly – that immigration adversely impacts quality of life. This prejudice contributed more than any other single factor to the Leave vote; there’s absolutely no chance a majority would have voted for Brexit were it not for the promise of reduced immigration. This was recognised by Britain’s ethnic minority communities, which invariably voted in large majorities to remain in the EU. The racism of the Brexit campaign is demonstrated with appalling clarity by the staggering increase in hate crime incidents in the weeks following the referendum.

Taking charge of the Brexit negotiations, Theresa May made it clear from the beginning that her priority was to restrict freedom of movement. Brexit means Brexit means xenophobia.

This xenophobia is not of course exclusively connected to Brexit; it was leveraged by the Brexiters in order to win the referendum, but it has a broader political purpose for capitalism: preventing unity of a multicultural multi-ethnic working class. The specific form of racism surrounding the Brexit campaign also chimes with cultural changes in Britain in recent decades. The brutal, flagrant racism that was meted out in previous decades to Irish, Jews, African Caribbeans, Asians and others is no longer socially acceptable in the way it was. Instead we have what Ambalavaner Sivanandan described as ‘xeno-racism’ – “it is racism in substance, but ‘xeno’ in form. It is a racism that is meted out to impoverished strangers even if they are white.” Those immigrants “coming over here and taking our jobs” are nowadays less likely to be Asians and Caribbeans, but rather Romanian and Polish – not to mention Nigel Farage’s asylum seekers and Boris Johnson’s Turkish EU citizens. Brexit has managed to both leverage and deepen this racism, and in so doing has strengthened the hand of the most reactionary elements of British society.

Brexit will make workers poorer

Brexit will harm large sections of the British economy, and the cost of this damage will inevitably be borne by the working class, since the owners of capital can more easily shift their investments to those areas that aren’t affected. As TUC General Secretary Frances O’Grady notes: “Other EU countries buy huge amounts of British goods and services. But if it’s harder to sell what the UK makes in Europe, big global firms are likely scale down their operations. That would result in big job losses, especially in sectors like manufacturing where half of exports go the EU.” These manufacturing jobs, threatened by Brexit, are typically paid significantly better than their service sector equivalents, so “even if jobs lost were replaced, we’ll be left with worse jobs on lower wages.”

The EU is Britain’s largest trading partner, constituting 44 percent of exports and 53 percent of imports. The TUC estimates that over three million jobs in Britain are linked to trade with the EU. Outside the EU single market, it will be more difficult to sell products and services made in Britain and to buy products and services from elsewhere. In the short term, this puts essential imports such as food and medicine at risk – Britain imports around 40 percent of its food, for example, and the vast majority of this comes from the EU. In the longer term, it leads to reduced productivity and reduced participation in the international division of labour. Tom O’Leary writes that, post-Brexit, “the economy will be operating behind a series of tariff and non-tariff barriers as others protect their markets. All of these will make the economy less competitive and will increase costs.” This cannot but have a detrimental effect on living standards.

EU funding in Britain will end immediately with Brexit. This will have a disproportionate impact on the poorer regions of the UK, particularly in Cornwall, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Even more significant would be the effect on public finances due to businesses closing or moving away from Britain, as well as from reduced immigration. The Economist puts the case bluntly: “Britain exports old, creaky people and imports young, taxpaying ones. More than 100,000 British pensioners live it up in sunny Spain; meanwhile, up to 100,000 working-age Spaniards brave the British cold… The government’s fiscal watchdog suggests that by the mid-2060s, with annual net migration of about 100,000, public debt would be roughly 30 percentage points higher than if that figure were 200,000. Taking back control comes with a whopping bill.” Beyond fiscal revenue, reduced immigration means a lack of people to do important work. For example, the staffing crisis in the NHS is expected to get much worse with Brexit.

For the myriad flaws of the EU, membership has brought some crucial benefits to British workers. As Jeremy Corbyn has pointed out, “there was no limit on working time for workers in Britain until the Working Time Directive, which also provided for rest breaks. Our rights to annual leave were underpinned by the EU too; we would not have a right to 28 days’ leave without that membership.” EU regulations mean that part-time workers (predominantly women) have equal rights with full-time workers; that a million temporary workers have the same rights as permanent workers. Freedom of movement means that these terms can’t (legally) be undercut within the EU – so ending freedom of movement would significantly deepen the ‘hostile environment’ in terms of labour rights for immigrants.

In the same 2016 speech, Corbyn pointed out that the most ruthless exploitation in Britain is not the result of EU neoliberal policy; in fact most EU countries are far better than Britain in terms of workers’ rights. “If we want to stop insecurity at work and the exploitation of zero hours contracts why don’t we do what other European countries have done and ban them? Zero hours contracts are not permitted in Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Poland and Spain.”

Outside the customs union, Britain will need to negotiate major trade deals. The most prominent of these is with the US, which will be well placed to exact horrific terms, including opening up much more of the NHS and education system to privatisation. As TJ Coles writes, “a Britain unshackled from Europe would strengthen US-UK relations and weaken the EU in preparation for a regulatory assault by the US” (op cit).

Post-Brexit trade deals will almost certainly mean opening up the British market for dangerous produce. As it stands, the EU bans the import of US-produced items such as hormone-treated pork and beef, genetically-modified cereals, and chlorine-washed chicken. US capital and its Tory allies are desperate to put an end to these restrictions, and Brexit gives them the perfect opportunity.

Brexit means worse conditions for workers. More casualisation, more privatisation, less regulation, less union power, fewer restrictions on big business. This is exactly why a significant section of the British ruling class is so keen on Brexit, and why the rest of us should resolutely oppose it.

EU state aid rules are not the problem

The proponents of Lexit, both within and outside the Labour Party, have built their case primarily on the idea that EU regulations regarding state aid to industry will stand in the way of a programme of state-led investment and nationalisation. Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn has unfortunately lent credence to this theory.

There are three major problems with this. The first is a simple practical matter: Jeremy Corbyn is not the prime minister, and Labour is not in government. Efforts to change that situation are welcome and necessary, but it is very likely the Tories that will be implementing Brexit, and the Brexit they have in mind has nothing whatsoever to do with nationalisation and the redistribution of wealth. Quite the opposite. However problematic the EU state aid rules might be, the British post-Brexit government is highly unlikely to replace them with anything better.

The second problem is that Labour’s ‘Soft Brexit’ wouldn’t release Britain from EU state aid rules. The Labour leadership has repeatedly stated that its Brexit vision includes continued membership of a comprehensive customs union with the EU. The chances of the EU signing up to such a deal whilst allowing exemptions on its core elements are approximately nil.

The last obvious problem with the idea that EU state aid rules get in the way of public ownership is that it’s not actually true. Britain’s relentless privatisation over the course of the last 40 years has been pushed by successive British governments; it has been cooked up in Whitehall, not Brussels. In fact, as TSSA general secretary Manuel Cortes notes, “Britain spends far less than the EU average on state aid. If Britain were to match the proportion of spending of Denmark it would mean an extra £24 billion a year; if Britain matched Hungary, we would spend an additional £34 billion.”

George Peretz QC, a barrister specialising in public law and tax issues, writes that, “as far as nationalisation is concerned, EU law raises no objection. Anyone who knows the continent knows that in most countries most operators in the sectors mentioned by Corbyn [postal services, water, railways and banks] are state-owned… Many member states have been able to provide large subsidies to their rail and postal operators to ensure high quality universal services… What the state aid rules prevent is ill-targeted aid, such as the money repeatedly thrown down the black holes of national flag carriers or tax exemptions given to large multinational companies in return for locating in the state concerned.” In short, the EU state aid rules would have little or no impact on the progressive programme of state-led investment envisaged by Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell.

Britain leaving the EU will not weaken imperialism

Another Lexit idea is that the EU – an organisation composed of capitalist countries – will be diminished by the UK’s departure, and therefore imperialism as a whole will be weaker. This rather ignores the fact that Britain was an imperialist country before joining the EU and will remain an imperialist country once it leaves. Because the UK will, for reasons described above, lean more towards the US (which by any reasonable definition represents the most aggressive form of imperialism on the planet in the present era), the balance of forces between imperialist blocs will be shifted somewhat, but not in a way that benefits the masses of the world seeking to free themselves from neocolonial domination.

Laughably, some of the leading Brexiters have talked about Britain’s departure from the EU paving the way for the establishment of an ‘Empire 2.0’ built on stronger trading links within the Anglosphere and the Commonwealth. This is the stuff of sheer nostalgic fantasy. In truth, as pointed out by Tottenham MP David Lammy, “leaving the EU will not free us from the injustices of global capitalism: it will make us subordinate to Trump’s US.” Britain is not a major player in the global economy any more; Brexit has come a century or so too late for these nutty delusions. If an ‘Empire 2.0’ were to come into being, “its centre would not be in London but in Washington. It would be an American, not a British empire” (O’Toole, op cit).

In foreign policy terms, Brexit stands to push Britain towards a more aggressively reactionary position. Ministers are already talking about how they’ll be able to ramp up sanctions against Russia, for example. Aligned to Trump’s US, Britain would be under intense pressure to join the sanctions regime against Iran, to support US policy on trade with China, and to scale back participation in global environmental cooperation. Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson has made it all too clear that “Brexit represents an opportunity for Britain to boost its global military standing in response to the threats posed by Russia and China”.

From a strategic anti-imperialist point of view, a relatively stronger EU and relatively weaker US would constitute a more favourable balance of forces; this much was recognised by Chinese president Xi Jinping in 2015: “China hopes to see a prosperous Europe and a united EU, and hopes Britain, as an important member of the EU, can play an even more positive and constructive role in the promoting the deepening development of China-EU ties.” The subtext is clear enough: a US-dominated unipolar world is the most dangerous possible scenario.

There is also the profoundly important issue of Ireland to consider. Brexit poses a serious threat to the Irish economy in both north and south, to the Good Friday Agreement, and to the wider cause of Irish unity and self-determination. The peace process has turned the hard border into a soft border, with an increasingly integrated economy and a much-reduced presence of the British armed forces on the streets of the north. These streams have fed into a powerful (albeit slow and winding) river headed towards peaceful reunification.

Brexit will inevitably affect economic cooperation between north and south, and, if the hard-Brexiters get their way, could well dismantle all the progress of the last two decades. A land border and customs checks would be extremely disruptive and would contravene the terms of the GFA. This would lead to rising dissatisfaction and, very likely, increased sectarian tensions. With a coalition of the Democratic Unionist Party and the Conservative and Unionist Party in power in Westminster – probably with an even more nutty right-wing leadership than at present – we could well see an increased presence of the UK armed forces, under the direction of an emboldened, militantly unionist government that wouldn’t hesitate to employ any measure in defence of the union. Various commentators have noted that a no-deal Brexit could mean a return to direct rule. There’s nothing anti-imperialist about that.

Remain and reform

None of this is to claim for the EU any progressive nature. The precursor organisation to the EU was formed as a bulwark against Soviet socialism and to represent the interests of US-dominated western capitalism in Europe. The need to provide European workers with an alternative to socialism meant that the European Economic Community tended to promote a relatively benign, social-democratic form of capitalism. With the decline and fall of the Soviet Union and its Central/East European allies, the neoliberal consensus seeped out of the Anglosphere and into the heart of Europe. As Fintan O’Toole writes: “Being angry about the European Union isn’t a psychosis – it’s a mark of sanity. Indeed, anyone who is not disillusioned with the EU is suffering from delusions. The slow torturing of one of its own member states, Greece, was just the most extreme expression of a desire to blame the debtor countries alone for the great crisis that hit the Eurozone in 2008” (op cit).

However, as noted above, the neoliberal consensus was not invented by the EU, and the EU is not responsible for imposing it on Britain. Within the EU, leftists in Britain are better placed to fight free-market fundamentalism across the continent. In the words of Manuel Cortes: “Solidarity means standing shoulder to shoulder with our sisters and brothers in socialist parties across the EU demanding a Europe for the many as an integral part of building a better world.” This was precisely the meaning of Corbyn’s “Remain and Reform” slogan. There are plenty of examples of a progressive agenda being successfully advanced within the EU; indeed, the various protections for workers currently embodied in EU regulations were won through continent-wide class struggle.

Where do we go from here?

The progressive project represented by Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour Party could provide the basis for an unprecedented unity in this country. The NHS and the welfare state are among the best things the British people have created. We are well placed to expand and innovate in these areas, along with green energy, poverty alleviation, inequality reduction and scientific research; we can develop a global outlook that embraces multipolarity and opposes war. But any prospects for a successful socialist-oriented government in Britain would be seriously undermined by a Tory Brexit that would be accompanied by economic crisis, deep social divisions and a foreign policy designed by John Bolton.

It would be much better to remain in the EU than to proceed with this hard-right scam. It is the duty of all socialists and progressive people to do everything within their power to avoid a “hard Brexit” or a “no-deal Brexit”. Preferably this means remaining in the EU, but if this isn’t possible, we should work towards Brino – Brexit in name only. Labour has taken some steps towards that sort of position, pushing for a comprehensive, permanent customs union with the EU. However, the EU negotiators have repeatedly made clear that any customs union would be conditional on maintaining free movement of labour. The next critically important step for the Labour leadership and the trade unions is to unambiguously accept freedom of movement. That shouldn’t be difficult, because freedom of movement is a fundamentally positive thing. It benefits both immigrants and non-immigrants. The numbers show again and again that immigrants are net contributors to the economy. Indeed, our economy is heavily reliant on immigration. With freedom of movement, immigrants coming here from the EU are protected by EU-wide labour legislation which means they can’t be ruthlessly exploited at the levels British capital would like. If those protections were taken away, it would drive down wages and conditions for everyone. And besides the economic aspect, there is the basic political principle of promoting maximum unity of the working class. Any sheepishness or caginess about this issue feeds into a growing, dangerous trend of racism and xenophobia.

We should recognise the Brexit project as a multi-pronged attack on the working class, and we should take all necessary measures to defend ourselves against it.

Book review: Simon Hannah – A Party with Socialists in it: a History of the Labour Left

A slightly modified version of this article first appeared in the Morning Star on 03 March 2018.

Simon Hannah’s recently-released book ‘A Party with Socialists in it: a History of the Labour Left’ provides a timely, concise and very readable account of the ongoing struggle between left and right within Labour.

The title is inspired by Tony Benn’s comment that “the Labour Party has never been a socialist party, although there have always been socialists in it”, and the text charts the attempts of those socialists to promote their vision over the course of the past 118 years. This fight has been taken on by numerous parties, groups and factions, including the Independent Labour Party, the Communist Party of Great Britain, the Socialist League, the Socialist Fellowship, the Young Socialists, Militant and the Socialist Campaign Group. Hannah details how such efforts have in the past been frustrated by ‘pragmatic’ right-wingers, who until recently dominated the commanding heights of the party.

The author also describes the various Labour governments, led by Ramsay MacDonald (1924, 1929-31), Clement Attlee (1945-51), Harold Wilson (1964-70, 1974-76), James Callaghan (1976-79), Tony Blair (1997-2007) and Gordon Brown (2007-10). Analysing these administrations without rose-tinted glasses, Hannah demonstrates that they tended to controlled by the right and were focussed more on keeping British capitalism happy than on winning meaningful gains for the working class. Even the much-celebrated Attlee government was generally committed to the capitalist consensus, and its historic gains (the establishment of the NHS and the building of thousands of council homes) were deeply compromised by its enthusiastic support for the creation of Nato and its role in the genocidal war on Korea.

Studying the long, tortuous and often torturous journey of the Labour left, it becomes increasingly clear that socialists within and around Labour have never been in a better position than they currently are. Previously, even when leftists have held key leadership positions, they have never managed to win control of the party machine and the support of the unions. As Ralph Miliband once bitterly noted, “the ‘broad church’ of Labour only functioned effectively in the past because one side – the right and centre – determined the nature of the services that were to be held, and excluded or threatened with exclusion any clergy too deviant in its dissent.” (Socialist Advance in Britain, 1983)

Today’s situation is therefore unprecedented. The membership has grown from 150,000 in 2014 to almost 600,000 today, and these new members are largely progressive and committed. Furthermore, the party is becoming more democratic and responsive to the membership – unlike in the Kinnock and Blair years, when constituencies, branches and activists were treated with contempt.

Meanwhile, key trade unions have shifted to the left in response to austerity and the betrayals of Blairism. Most unions have therefore thrown their weight behind Corbyn and his team. This is an important development, as the unions have tended to be a force of centrist ‘moderation’ within Labour, resisting the more radical, anti-racist and anti-imperialist views put forward by the likes of Jeremy Corbyn and Diane Abbott.

The surprisingly good showing for Labour in the 2017 general election has forced most Labour MPs to stop (or at least pause) their attempts to get rid of Jeremy. The left now has a majority on the National Executive Committee and is establishing its leadership at the constituency and branch levels. For the first time, socialism is becoming hegemonic within Labour.

Crucially, the left also has a large activist base. Hannah makes the important point that Corbyn was well-known in the wider progressive movement long before the 2015 leadership election, and that the camaraderie that had developed between left Labourites and the thousands of anti-war and anti-austerity activists has its roots in the work of the Stop the War Coalition and the People’s Assembly, among other groups and campaigns.

This all adds up to an opportunity that is too good to throw away.

The book would be improved by the removal of a couple of left-sectarian shibboleths (Soviet socialism was “bureaucratised and killed” by Stalin in the mid-1920s, apparently, and the Alliance for Workers’ Liberty was subjected to a “red scare” led by the Momentum leadership around John Lansman). These notwithstanding, it is a very readable and well-researched history, and could hardly be more relevant for the political moment we are living through and participating in.

Jeremy Corbyn and the possibilities for building a lasting socialist and anti-imperialist movement

This wasn’t supposed to happen. When Jeremy Corbyn announced, a few months ago, that he was throwing his hat in the ring for the Labour leadership contest, many – myself included – were sceptical. The whole project seemed irrelevant and hopeless; even if he did get sufficient MP nominations to get on the ballot, everybody knew that his candidature would end in ignominious defeat. The episode was set to provide yet more proof (as if any were needed) that the entire ‘left Labour’ project was long past its sell-by date.

The bookmakers, whose predictions are generally far more reliable than those of the left commentariat, gave Corbyn odds of 200-1 against (thereby producing quite a windfall for a few startlingly over-optimistic British socialists).

Then something very strange and unprecedented happened; something that nobody could have predicted. Ordinary people around the country became interested in the campaign, excited at the possibility – no matter how remote – of having an old-fashioned leftist as leader of the opposition. Thousands of people joined the Labour Party. Tens of thousands signed up as registered supporters, specifically in order to vote for Corbyn. The unfaltering vitriol of the mainstream press – including much of its supposedly left-leaning branch – and the impassioned pleas of Blair, Brown and the rest of the Labour grandees proved totally ineffective in stemming the tide of popular support for the Corbyn campaign (in the case of Blair and Mandelson, their contributions only served to heighten Corbyn’s popularity!). Huge numbers of people signed up to help out, manning phone lines, distributing leaflets, building websites, spreading the word on social media.

Corbyn’s campaign meetings, nearly a hundred of them, were all packed. Many times he had to address overspill rooms – including, in London, speaking to a crowd outside from atop a fire engine provided by the Fire Brigades Union. The buzz surrounding the campaign was reminiscent of the excitement surrounding the Scottish independence referendum last year. For many young people in England, the Corbyn leadership campaign represented the first time in their lives that anything within the realm of mainstream politics had felt interesting, relevant and worthy of their participation. The result was a landslide victory for Corbyn, the election of the most left-wing leader in Labour’s history, and a reversal of many decades of near-universal conservatism in the general political narrative.

There are too many variables to predict what will happen in the coming months and years, but what we can say for sure is that the emergence of a socialist, anti-monarchist, anti-Nato, anti-nuclear, anti-war, anti-racist, anti-neoliberal, veteran campaigner as leader of the parliamentary opposition in Britain is a hugely significant moment. As Seumas Milne notes: “By any reckoning, Corbyn’s election and the movement that delivered it represent a political eruption of historic proportions. The political conformity entrenched during the years of unchallenged neoliberalism has been broken.”

Why did Corbyn win?

What has changed? How is it possible that veteran left-winger Jeremy Corbyn could win the Labour leadership in 2015 – by a landslide – when veteran left-winger Diane Abbott only received 7% of the votes in 2010, or when veteran left-winger John McDonnell couldn’t get sufficient nominations to stand against Gordon Brown in 2007, or when veteran left-winger Tony Benn was defeated by an embarrassing margin in 1983?

There are a few key aspects that need to be considered.

-

Vast swathes of people are feeling more and more alienated, and are struggling economically to an ever greater degree. People have increasingly had enough of the vindictive neoliberalism that has dominated British politics for so long. The policies of ‘austerity’ are starting to impact people’s livelihoods in a very real way. Those hit worst are the most vulnerable, oppressed and disenfranchised: the immigrants, ethnic minorities, low-paid workers, casual workers, unemployed, disabled. But there is also a significant layer of the middle class that is being ‘proletarianised’ – no longer can people expect free education and a range of decent employment opportunities to choose from after university; nor can they expect any sort of affordable housing. A clear majority now faces declining living standards and prospects for the future, and Corbyn’s plain-speaking anti-austerity platform speaks to the needs of that majority far more effectively than the Tories, Lib Dems or New Labourites.

-

The last general election was a wake-up call. The resounding failure of Ed Miliband’s half-hearted, apologetically centre-left stance made it all too clear that people are not interested in a political process where, as Craig Murray puts it, “if the range of possible political programmes were placed on a linear scale from 1 to 100, the Labour and Conservative parties offer you the choice between 81 and 84.” The result of Labour’s pathetic platform is that we’ve ended up with “one of the most uncaring, uncompromising and out of touch governments that the UK has seen since Thatcher”. Furthermore, the Scottish independence referendum and the SNP’s extraordinary performance north of the border in the general election amply demonstrated that there is an appetite for anti-austerity, anti-war, left-of-Labour politics; that to adopt progressive stances is not to be unelectable.

-

There is emerging, belatedly, an understanding of the profoundly elitist and anti-popular nature of neoliberalism – the ‘free market’ capitalism that promotes economic growth via unrestrained exploitation. Twenty years ago, with the Soviet Union and its East European allies out of the way, and with a globalised ‘end of history’ declared, international capital no longer felt the need to pander even to the relatively tame social democracy offered by the likes of the Labour left. This was shoved aside in favour of a Thatcherite neoliberalism that, in the words of Stuart Hall, “evolved a broad hegemonic basis for its authority, deep philosophical foundations, as well as an effective popular strategy; that was… grounded in a radical remodelling of state and economy and a new neo-liberal common sense.” The workers and oppressed were deemed irrelevant. Mainstream politics was converted into the undisguised (as opposed to somewhat disguised) representation of the finance capitalist elite.

More recently, in response to a massive global recession for which the poor have been made to pay (while the banks are bailed out to the tune of trillions of dollars), a global fightback against neoliberalism has finally started to grow. This movement has been spearheaded by the wave of progressive governments in Latin America, but is also expressed in different ways by, for example, the rise of the Occupy movement; the coming to power of the Syriza government in Greece; the increasing popularity of Sinn Fein, SNP, Podemos, Die Linke, the Portuguese Communist Party, Portugal’s Left Bloc and other forces. This is the global context in which Corbyn’s victory should be understood.

On top of all that, the people around Corbyn have waged a highly effective and energetic campaign that has tapped into popular sentiment, building a momentum that has proven incredibly resilient in the face of the slander campaign being waged by the mainstream press.

It certainly helps that, in a political world that has become synonymous with corruption, dishonesty, spin, inhumanity and cynical self-interest, Corbyn stands out among mainstream politicians as being consistently principled, genuine, compassionate and honest. He’s a life-long activist against the worst injustices of capitalism, against racism, and against war. He has campaigned for policies that most reasonable people agree with: against wars, against austerity, against the bedroom tax, against privatisation, for taxing the rich, for a living wage, for the NHS, for welcoming refugees. As an MP over three decades, he has an admirable record of standing up for the poor and marginalised.

What does Corbyn stand for?

Corbyn’s election victory and the hype surrounding his campaign are more a reflection of Corbyn as an individual than of the Labour Party as such. The term ‘Corbynmania’ expresses this fairly clearly; after all, what other Labour leader can you imagine inspiring such a level of ‘mania’? Labour’s deeply uninspiring election platform was roundly rejected by the voters in May, handing David Cameron a majority government. ‘Corbynmania’ has arisen in spite of, rather than because of, the Labour Party’s record, and indeed it wouldn’t have been possible were it not for Corbyn’s record of voting against the party whip.

So to the extent that people are inspired by Jeremy Corbyn, what sort of political consciousness does this represent? What is the political framework associated with Corbyn?

The policies Corbyn is best known for are: opposing austerity; supporting the poor; supporting immigrants; opposing racism; protecting welfare; opposing war; opposing nuclear weapons; promoting re-nationalisation of key areas of the economy; protecting trade union rights; building social housing; ending homelessness; supporting public education and healthcare; exiting NATO; working for a united Ireland; supporting Palestine and progressive Latin America.

Corbyn isn’t proposing the overthrow of capitalism (more’s the pity!). His economic programme is not based on putting an end to the system of exploitation of man by man; rather, it expresses an anti-neoliberal vision that shifts the burden of crisis from the oppressed to the oppressors and which puts an end to savage cuts. His manifesto calls – in somewhat fluffy style – for “a fairer, kinder Britain based on innovation, decent jobs and decent public services.” Cuts should be reversed, important industries should be (re-)nationalised, the rich should pay their taxes, and cash should be printed in order to fund infrastructure spending.

Hardly extreme. As economist Michael Burke points out: “Jeremy Corbyn is the only candidate who is NOT proposing extremist economics. His policy aims to promote growth through increased public investment, funded by progressive reform of the current taxation system, and attacking the abuses of the £93 billion in annual payments for ‘corporate welfare’ in subsidies, bribes and incentives to the private sector. At the same time he opposes any attempt to make workers and the poor pay for the crisis and rightly argues that the deficit would close naturally with stronger growth”.

Corbyn’s appointment of Thomas Piketty, Ann Pettifor and Joseph Stigiltz to his economic advisory team indicates that his agenda is about building a credible consensus – within the framework of capitalist economics – for Keynesianism and against austerity. While this is by no means a Marxist programme, it represents a significant break with anything put forward by the political mainstream, and is clearly unacceptable to bulk of the British ruling class, which has worked feverishly to establish neoliberalism as an ideological norm, and which is irretrievably hostile to redistributive economics of any sort.

Foreign policy is another area where Corbyn’s platform resonates with a huge number of British people who oppose Britain’s wars of domination. His leadership election pledge on foreign policy reads:

No more illegal wars; a foreign policy that prioritises justice and assistance. Replacing Trident not with a new generation of nuclear weapons but jobs that retain the communities’ skills.

Corbyn is strongly opposed to any British military involvement in Syria, which the Cameron government is pushing strongly for. He correctly notes that a western bombing campaign actually feeds into the growth of Isis (“I don’t think going on a bombing campaign in Syria is going to bring about their defeat. I think it would make them stronger.”). He has also said that Labour should apologise for the destruction of Iraq, and suggested that Tony Blair could be convicted of war crimes. He opposes Britain’s membership of Nato and the west’s increasingly hostile position vis-a-vis Russia, noting that Nato has been “the major driver for the remilitarisation of central Europe”. He believes that “Britain’s role in international affairs needs to change to the promotion of conflict resolution and co-operation rather than using UK forces to achieve regime change”.

Being ‘tough on immigration’ is considered essential for anyone hoping to be elected to a position of power in England. Pandering to a racist, xenophobic, scape-goating agenda is par for the course – as exemplified by Labour’s notorious anti-immigration mug that appeared in the run-up to the last general election. In that context, Jeremy’s pro-immigration and pro-refugee stance is a breath of fresh air and is something that has won him support. Pointing to the racism and hypocrisy implicit in the mainstream narrative on immigration, Corbyn asks in a recent interview: “Are we actually going to see sort of armed guards all around Europe keeping out the poor and the desperate? Some of whom are victims of impoverishment which is a product of a whole lot of economic circumstances. Some are victims of wars which we have been involved with such as Iraq and the bombing of Libya… At the end of the Second World War there was a coming together of all of the wealthy nations to accept very large numbers of refugees because they saw that as a humanitarian crisis. Is it different because so many of these people come from Africa as opposed to Europe?”

The class enemy goes berserk

Predictably, the mainstream media machine has gone into overdrive in its attempts to bury the movement building around Corbyn. Britain’s newspaper columns have, since the very beginning of the Labour leadership campaign, been given over to an army of Corbyn detractors, from the right-wing fruitcakes of the Daily Mail to the (bulk of the) supposedly left-liberal luvvies of the Guardian. In an almost touching display of unity, the defenders of the imperialist status quo have got together to publicly fret about the possibility of Corbyn’s election ushering in an era of “class hatred, the indulgence of unionised labour, and the Soviet-style handing out of favours to party loyalists on the council payrolls.”

Who better than Boris Johnson to state the case against Corbyn?

“Can this be happening? Are they really proposing that Her Majesty’s Opposition should be led by Jeremy Corbyn? He believes in higher taxes and a bigger deficit, and kowtowing to the unions, and abandoning all attempts to introduce competition or academic rigour in schools – let alone reforming welfare. He is a Sinn Fein-loving, monarchy-baiting, Israel-bashing believer in unilateral nuclear disarmament.”

The press have had a field day denouncing Corbyn over his long-standing relations with Sinn Fein; his support for revolutionary Venezuela; his involvement in the Stop the War Coalition, Cuba Solidarity Campaign and Palestine Solidarity Campaign; his stated belief that Hezbollah and Hamas are a necessary part of any valid Middle East peace process. The mad zionists of the Jewish Chronicle lost no time in slinging slanderous accusations of anti-semitism. But of course all this was nothing in comparison to the quantity of mud hurled when he appeared at a Battle of Britain commemoration and failed to sing along with God Save the Queen!

The press have had a field day denouncing Corbyn over his long-standing relations with Sinn Fein; his support for revolutionary Venezuela; his involvement in the Stop the War Coalition, Cuba Solidarity Campaign and Palestine Solidarity Campaign; his stated belief that Hezbollah and Hamas are a necessary part of any valid Middle East peace process. The mad zionists of the Jewish Chronicle lost no time in slinging slanderous accusations of anti-semitism. But of course all this was nothing in comparison to the quantity of mud hurled when he appeared at a Battle of Britain commemoration and failed to sing along with God Save the Queen!

David Cameron apparently worries that, “by leaving Nato, as Jeremy Corbyn suggests, or by comparing American soldiers to Isil … it will make Britain less secure.” Chancellor George Osborne believes that Corbyn’s election will create “an unholy alliance of Labour’s leftwing insurgents and the Scottish nationalists” that would pose a threat to Britain’s national security. It seems this is such a serious concern that there have even been rumblings of a military coup in the event that a Labour government was elected under Corbyn’s leadership.

The level of class hatred directed at Corbyn by the capitalist elite and their media tells us how much of a threat they seem him as.

Possibilities for the working class and oppressed

That the most left-wing, avowedly socialist member of parliament should be elected leader of the numerically largest political party in the country reflects a certain rising level of consciousness of the masses. In world-historic terms, this is still a long way from being a revolutionary consciousness, but ‘you can only start from where you are’. Every step forward is valuable and presents an opportunity for further advance. The sudden appearance of a leftist agenda at the very least creates space in which socialist and anti-imperialist voices can be heard, and in which radical ideas can flourish. For those who have lived through very tough decades of rightward drift in Britain and elsewhere, such space is clearly full of possibility. A recent statement by the US-based Party for Socialism and Liberation puts it well:

“Along with the dramatic rise of new mass movements against austerity throughout Europe, as well as progressive movements in the US, Latin America and elsewhere, it has become clear that the long period of reaction that began in the late 1970s and greatly accelerated under Margaret Thatcher in Britain and Ronald Reagan in the United States is drawing to a close. A new period of resistance to monopoly capitalism/imperialism is opening up, potentially leading to a revival of not only the trade unions but the revolutionary workers’ movement throughout the world. That this initial revival of anti-capitalism and socialism is being frequently, although not exclusively, expressed through the vehicle of electoral politics is to be expected in the first stage.”