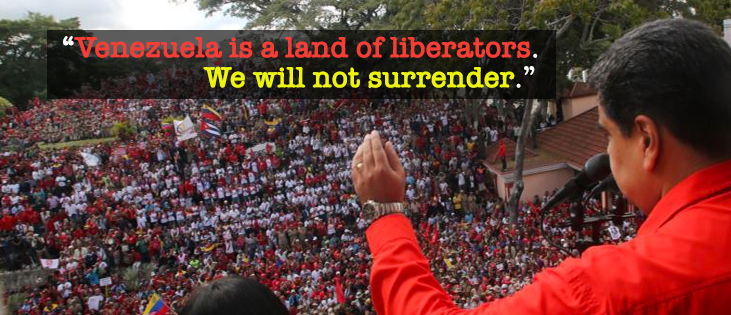

Most governments in the world enjoy precious little popular support. For example, when British prime minister Theresa May was forced to announce her resignation in May 2019, the masses didn’t rush out to the streets to declare their undying fealty; more like, the ground shook with the simultaneous muttering of the words “good riddance” from millions of homes and workplaces throughout the country.1 It may then have come as a surprise to some when, in early 2019, millions of ordinary Venezuelans – working people, peasants, students, barrio-dwellers – flocked to the streets to defend their elected government from an attempted coup.

Their appearance was a response to the little-known Venezuelan politician Juan Guaidó declaring, on 23 January, that he was the legitimate president of Venezuela.2 His announcement was particularly curious given that the Venezuelan presidential election had taken place just eight months previously and his name didn’t even appear on the ballot paper. Although Guaidó’s claim to the presidency had all the credibility of the average new-age mystic’s claims to divinity, the governments of the US, UK, Canada, Brazil, Colombia and the majority of the EU countries were quick to recognise his authority.

Guaidó had pinned his hopes on winning the support of key figures in the military and significant sections of the working classes. The latter in particular have suffered badly over the last few years, the result of sanctions, US-directed economic destabilisation and low oil prices. It was perhaps not total fantasy that they might lend their support to anyone that promised a way out of the current mess; to someone who had the ‘connections’ necessary to call off Washington’s attack dogs. Such blackmail tactics are nothing new. They’ve been used around the world, from Nicaragua to Zimbabwe, occasionally with some success. If you suffocate someone and then promise to let them breathe, there’s at least a decent chance they’ll accept whatever strings you attach.

However, the Venezuelan masses didn’t follow that script. Just as they did in April 2002 – when Venezuela’s business class joined forces with the yellow CTV union to seize power – the people of the barrios (shanty towns), the low-paid workers, the tenant farmers, the Afro-Venezuelans, the indigenous, the women, the LGBTQ+ coordinated with the military in order to defeat the coup and to defend their revolution.3

This says something important about the nature of the ongoing political struggle in Venezuela. It shows that the radical governments of the last two decades have achieved something very significant that goes beyond the economic benefits accrued to ordinary people, beyond the millions of homes built, beyond the provision of healthcare and education services. What has been created in Venezuela isn’t just a benevolent state; it’s a democratic revolutionary process that has given the working masses a voice, a stake in society. This process has politicised the millions, mobilised them, empowered them, drawn them for the first time into the running of their own society. It has taken up their interests and developed structures that allow them to take up their own interests. That’s why millions of Venezuelans defend their state even as it faces a level of systematic sabotage and destabilisation that’s creating widespread suffering.

This article explores the significance of the Venezuelan revolutionary process and the crucial importance of defending it for socialists around the world.

A path to socialism in the 21st century

Analysing the experiences of the Paris Commune of 1871, Marx started to develop his ideas around the political framework needed for building socialism, famously noting that “the working class cannot simply lay hold of the ready-made state machinery and wield it for its own purposes”.4 That is, the capitalist state is set up specifically to preserve capitalism; it is in essence just a “committee for managing the common affairs of the whole bourgeoisie”5, and therefore the working class and its allies will have to replace it with their own state, one designed to preserve and build socialism. This is precisely what the oppressed masses of Russia, Vietnam, Korea, China and Cuba did.

The advantages of stripping the capitalist class of its power are clear enough. Given a state set up to defend private property, capitalists can easily find ways to re-consolidate their power even when they find themselves occasionally having to cope with left-wing governments. The experience of Salvador Allende’s government in Chile (from 1970 to 1973) provides some of the strongest evidence in support of Marx’s theory of the state. Allende was a Marxist; his Popular Unity government aimed to build a society organised in the interests of workers and peasants. After several attempts, he won the presidential election in 1970, and the country was quickly swept up in an exciting and all-encompassing democratic process, nationalising the copper mines, tackling inequality and oppression, and inspiring millions of people to get involved in building a new Chile.

From the moment of Allende’s election, the US intelligence agencies worked with the Chilean elite to try and prevent his being inaugurated, and then worked systematically for three years to destabilise the country at every level. US president Richard Nixon ordered the CIA to “make the economy scream”6 in order to unseat Allende. The bulk of the leadership of the armed forces, inherited from 150 years of plutocratic rule (and colonial Spanish rule before that), aligned themselves with the old ruling classes and, with the backing of their friends in the US, conducted a coup against Allende. Thousands of leftists and trade unionists were murdered, and a brutal capitalist dictatorship was installed.

Many concluded from the Chilean experience that the only path to socialism was, after all, “the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions”7 and the establishment of a workers’ state – a dictatorship of the proletariat. After all, Allende was overthrown by the capitalist state that he was putatively in charge of. The counterfactual, then, is that if Allende had led an armed revolutionary movement and had been able to “break up, smash the ready-made state machinery”,8 Chile could have remained on the socialist path.

Which would be all very well, but for the non-trivial problem of forcibly overthrowing capitalist states, which is harder than it sounds.

The period from the late 1960s to 1980 witnessed the victory of liberation movements in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Mozambique, Angola, Guinea Bissau and Zimbabwe and elsewhere, as well as socialist-oriented revolutions in Nicaragua, Grenada, Afghanistan, Somalia, South Yemen and Ethiopia. The earlier part of that period also saw an upswing of radical activism in the west. Those years can reasonably be considered the end of the first wave of socialist advance. The ensuing two decades were characterised mainly by retreat: the decline and fall of the Soviet Union and its European allies;9 and the emergence of neoliberalism as the hegemonic global economic system. The socialist movement lost its first revolutionary base area. Unions and traditional networks of solidarity were broken down. Workers became ever more atomised. Even the limited social democracy constructed in much of the capitalist ‘west’ came under attack from deregulation, privatisation, de-unionisation and generalised marketisation.

The Global South meanwhile was subjected to abhorrent ‘structural adjustment’, putting an end to decades of slow but steady improvement in living standards.10 In the handful of socialist countries that survived the counter-revolutionary juggernaut of 1989-91, survival required tough choices that seemed to run against the natural trajectory of socialism: the expansion of market forces and foreign capital in China,11 and opening up to mass tourism and tourist-related small business in Cuba.

In the same period, imperialist states leveraged the technological revolution to bolster their defences against political revolution. Military and surveillance technologies advanced (and continue to advance) rapidly, and the techniques of political propaganda reached extraordinary new levels of sophistication, making Orwell’s cliched portrayal of a Soviet 1984 look positively quaint. In 1917, the Bolsheviks were able to win power because Russia was, in Lenin’s words, the wooden link in an iron chain.12 Today’s chain is made of hardened steel, and it’s the iron link that’s the weak one.

This is the context in which Venezuela’s Bolivarian Revolution should be understood. In a time of hopelessness, a time of neoliberal domination, a time of socialist defeat and the “end of history”13, a time of brazen military attacks on countries that refused to conform to the Washington Consensus, Venezuelan revolutionaries found a way to break the chain, to capture power – albeit partial and heavily contested – and to start along the road to socialism.

While they had finally arrived in government through similar means to Allende’s Popular Unity (with Hugo Chávez winning the 1998 presidential election), their initial hold on power was much less tenuous as a result of the government’s support by much of the military. Chávez often stressed that the revolution had the means to physically defend itself. “I warned the Venezuelan oligarchy and the counterrevolutionaries not to make the mistake of believing that this peaceful revolution is an unarmed revolution. We are peaceful, but we are armed.”14 Victor Figueroa Clark notes in his biography of Allende that while the progressive states of modern-day Latin America do face many of the same challenges Chile did, they’ve been able to analyse the weaknesses of that process: “Success in overcoming these challenges has owed much to lessons learned from Allende’s overthrow”.15

Another aspect of building self-defence capacity has been the work done by the Venezuelan government over the course of 20 years to democratise society; to engage people in politics, to construct organisations of popular power, and to develop a legal framework that privileges the needs of ordinary people. The recently deceased Chilean political scientist Marta Harnecker16 observes, for example: “It is probable that Venezuela is the only country which has a ministry devoted to participation: the Ministry of Popular Participation and Social Development, which was created in mid-2005. One of its principal objectives is to remove obstacles and make it easier for there to be popular participation from below throughout the country.”17

From around 2005 onwards, the Bolivarian Revolution has been explicitly socialist in its direction. Highlighting the significance of Hugo Chávez’s speech at the World Social Forum in January 2005, at which Chávez first announced that his goal was to build socialism, Iain Bruce writes: “All of a sudden, here was a process that openly and deliberately claimed it was aiming for socialism. And that was something nobody in a similar position had dreamed of saying since long before the collapse of the Soviet bloc a decade and a half earlier… As such Venezuela has become the laboratory for a new cycle of revolutionary theory and practice.”18

In forging this path, Venezuela’s revolutionaries have played a crucial role in kicking off the second wave of socialist advance. The Bolivarian Revolution was the first sustained experiment in the construction of working class power in several decades. Moreover, its journey towards socialism has been combined with an insistent internationalism that sought the broadest possible anti-imperialist unity on a global scale. Venezuela has thus moved from the capitalist periphery – as a supplier of petroleum and beauty queens – to the socialist centre – as a supplier of inspiration and essential experience.

Why Venezuela?

Venezuela in the late 1980s and early 1990s was a country on the edge. Known for the extravagant tastes of its upper classes – the “Saudis of Latin America”, soaking in the country’s abundant oil reserves – Venezuela was one of the most unequal societies on the planet, and this inequality was getting worse by the day as a result of ruthless neoliberal policies.

In early 1989, then president Carlos Andrés Pérez announced a series of harsh austerity measures, including a 100% increase in the price of gasoline, an end to food subsidies, and price increases for electricity, water and other basic services. A few days later, the powderkeg of profound poverty, inequality and alienation exploded in the Caracazo, a mass rebellion in which the capital’s barrios rose up in response to an overnight hike in bus fares.19 This was “the most spectacular demonstration of a series of ‘IMF riots’ or ‘bread riots’ of the 1980s and early 1990s”.20 US-based political scientist George Ciccariello-Maher, author of We Created Chávez: A People’s History of the Venezuelan Revolution, writes that the Caracazo “was a full-scale insurrection whose participants stared revolution in the face only to suffer the crushing reply of the state’s iron heel.” Although it was violently repressed, “the Caracazo sounded the death knell of the old system, simultaneously reflecting and contributing to the inevitability of its collapse and thereby setting into motion the entire process that came after.”21

The Caracazo didn’t come out of nowhere. Spontaneous as it was, it was also connected to revolutionary networks of various kinds, some of which had operated for many decades.22 Some level of formal capitalist democracy had existed in Venezuela since 1958, when the military dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez (backed to the hilt by the US, of course) was overthrown. The democratic system that replaced the military dictatorship was, well, not very democratic. The two major parties, Acción Democrática and COPEI (Independent Political Electoral Organisation Committee), coordinated from the beginning to ensure the frictionless rule of big business, lubricated by the sharp repression of any forces of the left. Venezuela “increasingly became a showcase for a mildly reformist, yet stridently anticommunist government that served as a trusted US ally during the Cold War.”23

The repression against the Communist Party and the various organisations of radical workers and students led to armed insurrection. Throughout the 1960s, communist groups took up guerrilla warfare against the government, for a while united in a single organisation: the Armed Forces of National Liberation (FALN). The guerrilla movement didn’t succeed in its aim of overthrowing the state, although it did carry out some wonderfully audacious actions, including the kidnapping of United States Air Force lieutenant colonel Michael Smolen in an attempt to prevent the execution of the captured Vietnamese liberation fighter Nguyễn Văn Trỗi.24 By the end of the 1960s, the movement was “utterly divided, isolated from any serious mass support, and confronted a repressive state that enjoyed ever-increasing levels of legitimacy.”25 Apart from anything else, a China-inspired rural guerrilla struggle found it difficult to take root in what was already a highly urbanised society (more than 70 percent of Venezuelans were living in cities by 1970).

In spite of the near-comprehensive collapse of the guerrilla movement, its traditions and many of its participants didn’t vanish. Ciccariello-Maher notes: “Those radical energies from below that had generated the guerrilla struggle to begin with, those demands of the popular masses that the new democratic regime was either unwilling or unable to meet, did not simply disappear into thin air. Instead, the ostensible failure of the guerrilla struggle gave way to a dispersed multiplicity of revolutionary social movements, and former guerrillas themselves courted ‘legality’ in a variety of ways, with both sectors twirling helically around one another in a constant struggle to both revolutionise the state and avoid its tentacles.”26 These radical movements took root in poor urban communities and in industry, breaking the stranglehold of the pro-capitalist trade unions (which functioned essentially as branches of Acción Democrática).

So there was a diverse, experienced and creative left in Venezuela, with strong connections to the masses. With the emergence of Chávez as a nationally-known figure in the aftermath of his leadership of a failed military coup in 1992,27 many of these streams coalesced into a broad movement for change. After the election victory of 1999, many radical leaders – including several former guerrilla fighters – became key figures in the government.

Another important and surprising component of the Venezuelan left was to be found in the armed forces, which had several influential socialist and radical nationalist cells. Venezuelan academic Miguel Tinker Salas explains that “Venezuela’s military differs from similar institutions in Latin America that had been the sole domain of the landed or political elites: throughout much of its twentieth-century history, its officers and noncommissioned personnel have been drawn from diverse socioeconomic sectors of the population. The military provided many of these young officers a way to climb the social ladder. In the military they found like-minded colleagues who expressed concern about the direction of the country and the corruption evident in the political class.”28 Hugo Chávez himself, a man of decidedly humble origins, of mixed African and indigenous descent, reached the position of lieutenant colonel in the Venezuelan Army.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, recognising the unusual nature of the Venezuelan military, revolutionary groups thought of forming a ‘civic-military union’ to overthrow the existing order. This is the milieu in which Chávez developed his ideas. His older brother Adán was involved with the Party of Venezuelan Revolution (PRV), one of the parties that arose from the ashes of the guerrilla movement, led by Douglas Bravo.29 Chávez for a time held regular meetings with Bravo, who later became (as he is now) an ultra-left critic of the Bolivarian Revolution. As Richard Gott puts it, “Chávez did not emerge from a vacuum. He was the heir to the revolutionary traditions of the Venezuelan left.”30

These then were the key objective factors that contributed to Venezuela being able to take the lead in the second wave of socialist advance: stark poverty and widening inequality; the hegemony of neoliberal economics; widespread frustration at decades of corrupt, phoney democracy; the existence of a capable and experienced radical left; and the existence of a progressive trend within the military. Thus an environment existed in which a social transformation was possible. It then took the creative genius, courage, determination, energy and compassion of Hugo Chávez to develop a specific programme – rooted in pro-poor radical nationalism – that could win over a popular majority.

A society run in the interests of the masses

The struggle for dignity is called Bolivarianism in Venezuela; in Cuba, this struggle is called socialism. (Fidel Castro)31

Is Venezuela a socialist country? It’s a complex and contested question, since not everybody is agreed on what socialism is and there’s no accepted set of measures for defining a given society as officially ‘socialist’. Most people agree that Cuba is socialist and that the US isn’t; between those points lies debate and controversy. What we can usefully say is that Venezuela is moving in the direction of socialism; it is undergoing a process of democratisation, through which power is increasingly wielded by, and in the interests of, working people rather than the owners of capital. Definitional problems aside, this is surely the important thing: the direction of travel, towards “liberation from imperialist domination, the construction of the unity of the peoples of Latin America, and the establishment of genuine democracy that serves its workers.”32

The central focus of the Venezuelan state is to improve the lives of its people: to eliminate poverty, to improve access to education and healthcare, to engage people in the organisation of their own lives, to make dignified housing available to everybody, to tackle all forms of discrimination, and to position Venezuela within a rising multipolar system that rejects imperialism. Its government has broken with free market fundamentalism, and has supported public and cooperative ownership. It is friendly to trade unions and social movements, and it works to empower workers, peasants, indigenous people, Afro-Venezuelans, women and youth. It is, in short, a society run in the interests of the masses.

The major class base for the Venezuelan government is the poor majority, “hitherto disorganised, effectively out of reach of traditional politics”.33 The most numerous element is the non-privileged working class, typically living in barrios and working in the informal sector. This is the section of the population that had been persistently ignored by Venezuelan governments and indeed by the wider world. Prior to 1999, such workers had not been unionised, and had only limited access to basic services. In addressing itself primarily to this section of the working class, the Chávez government broke with Latin American Marxist orthodoxy, which had tended to focus on either the industrial working class or the peasantry (according to circumstances and/or ideology). Furthermore, the Venezuelan state has allied itself with all oppressed groups and popular struggles: for racial and gender justice, for indigenous rights, to end discrimination against LGBTQ+ people, to conserve the environment. As such, it has become a powerful political tool of all the oppressed.

The Chavista conception of socialism is, in the words of Marta Harnecker, “a new collective life in which equality, freedom, and real and deep democracy reign, and in which the people plays the role of protagonist; an economic system centred on human beings, not on profits; a pluralistic, anti-consumerist culture in which the act of living takes precedence over the act of owning.”34 This is what Venezuelans, in the face of great difficulty and resistance, are building.

As an aside, it’s worth discussing the fact that Chávez didn’t always present the Bolivarian Revolution as being ‘socialist’; the process was above all ‘Bolivarian’. For all the things he was, Simón Bolívar (the leader of Venezuela’s independence war of the early 1800s and an insistent proponent of Latin American unity) could not reasonably be described as a socialist. But Chávez recognised that, at least in the late 1990s, ‘socialism’ was a dirty word for most Venezuelans. “In those days even the left hid the socialist banner,” Chávez said. “Almost no movement on the left in the Americas, with the exception of Cuba, lifted this banner. The big parties of the left distanced themselves from the socialist project and the word itself disappeared from the political lexicon.”35 In the figure of Bolívar – Venezuela’s national hero – Chávez saw the opportunity to get people on board with a progressive project on the basis of continuing Bolivar’s work, that is, completing the national democratic revolution, shaking off the domination of foreign powers (Spain in Bolívar’s time, the US in Chávez’s time), and working towards continental solidarity and unity. Leveraging Bolívar’s legacy was controversial in some quarters. Veteran journalist and Latin Americanist Richard Gott writes that most Marxist writers perceived Bolívar as “a typically bourgeois figure whose actions had only served the interests of the emergent imperial power of the time… For years, this caricature portrait of Bolívar as an imperialist stooge effectively precluded the left from examining his more positive characteristics.”36 However, Chávez instinctively understood the value of Bolívar’s legacy for uniting the largest possible section of the population around progressive goals. Crucially, the bulk of the military were much more immediately favourable to Bolívar than to Marx.

In economic terms, Venezuela has developed an alternative model of a mixed economy that rejects neoliberalism and incorporates socialist concepts. From very early on in the Chávez presidency, Venezuela emphasised close coordination with other oil producers in order to raise global oil prices, which it then used to fund radical social programmes with unprecedented reach.

The poverty rate in 1999 was in the region of 50 percent.37 Extreme poverty was around 20 percent. Within a few years, overall poverty was halved, and extreme poverty reduced to 5 percent as a direct result of government interventions. Miguel Tinker Salas observes that the massive public social investment, much of it carried out via a series of misiones (missions), “has had a significant impact on the lives of millions of people in Venezuela. The missions have been funded with the profits generated from PdVSA [Petróleos de Venezuela, the Venezuelan state-owned oil and natural gas company]… The revenue the government allocates for social spending has increased dramatically in the last decade, upwards of sixty percent according to some estimates. The number of missions has increased significantly to over twenty-five different programs, addressing health, literacy, education, sports, identity, land reform, senior citizens, the indigenous, culture, music, children, pensions, and energy, among others.”38

As part of the Barrio Adentro mission, several thousand clinics and diagnostic centres have been built to provide medical services to poor communities that previously had no such access. (This programme has been constructed with the assistance of thousands of Cuban doctors, whose services are paid for with cut-price Venezuelan oil).39 In more recent years, Barrio Adentro has been expanded to provide a more integrated healthcare approach, including exercise facilities and nutrition classes. According to Richard Gott, “the scale of Barrio Adentro was something entirely new. I visited several of these Cuban-run health centres in 2003 and 2004, in both town and country, and the enthusiasm and commitment of the Cubans and their warm reception by local people were clear indications of the forward march of the revolution. Many of the Cubans had already had experience of working in Third World countries – in Haiti and Honduras, in the Gambia and Angola – and this was their first chance to see a Latin American society so dramatically divided between rich and poor. They provided a local health service twenty-four hours a day, week in week out, and had soon become a familiar institution in the localities.”40

Misión Robinson deployed a network of instructors to teach literacy to the over one million adults that were illiterate in 2003. Just two years later, Unesco declared Venezuela as a “territory free from illiteracy”.41 Per capita spending on education increased 51 percent between 2003 and 2007.42 Millions of children have been provided with free laptops, running a customised version of Linux developed by the Venezuelan government, in line with its embrace of open source software.43

The housing mission – Misión Vivienda – was launched in the early 2000s to address Venezuela’s housing crisis, building hundreds of thousands of housing units in integrated housing zones with education and healthcare facilities. According to the most recent estimates, 2.3 million homes have been built (Venezuela has a population of 32 million).44 These apartments are typically sold to families with long-term low-interest rates of credit.

An array of businesses have been nationalised,45 and there have been numerous experiments with worker management and collective ownership.46 PdVSA has been brought under strict government control. Grassroots communal councils have been set up across the country with a view to engaging the masses and building a more meaningful democracy.47 Ciccariello-Maher writes that local communal councils started to be established throughout Venezuela in 2006. “Within one year, 18,320 communal councils had been established, and that number has since exceeded 40,000. According to the 2006 law, these councils seek to ‘allow the organised people to directly manage public policy and projects oriented toward responding to the needs and aspirations of communities in the construction of a society of equity and social justice’”.48 The result has been a remarkable democratisation. “A whole section of Venezuelan society, the poor in general but in particular the urban poor of the Caracas hillsides, several millions of people who had been buried in silence, obscurity and neglect, have suddenly ‘emerged’ from the shadows and established themselves as actors, as protagonists both of their own individual stories and of the nation’s collective drama.”49

The Venezuelan state is in the process of becoming a workers’ state. Its leadership has not been in a position to dismantle the capitalist state, but it is gradually reducing its scope whilst building up a socialist alternative.

The Egyptian Marxist Samir Amin reflected on his trips to Venezuela and the differences between the pre-Bolivarian and Bolivarian eras:

I found a country that had nothing in common with the one I had known. A true social revolution — it is not excessive to say so — had occurred in the sense that, finally, we could see Indians, blacks, and mixed race people —the majority of the population — elsewhere than in the street! Until the arrival of Hugo Chávez, all the powers in the country were reserved for the whitest of the white, strictly European in origin. This change is not, in my opinion, of secondary significance. It is the proof that political power (but nothing more, understand) has passed to the representatives of the Venezuelan people as it really is. It is the proof that the Chávez government is not that of some soldier — one of mixed race, at that — but the result of a real mass movement… That is what I call a revolutionary advance.50

Nicolás Maduro, interviewed by the BBC, recently outlined his government’s key objectives: “We are in a battle … to reduce poverty, misery, to increase job capacity, to establish a social security system to protect 100% of our pensioners, to establish a public health system that reaches all the Venezuelan population… We have made a commitment between 2017 and 2025 to reach a state of zero poverty and we are going to accomplish it.”51

Reflecting on the Venezuelan state’s priorities, actions and support base, it’s clear that it is a socialist-oriented state, that is, it is moving in the direction of socialism. Its survival is therefore of obvious importance to socialists worldwide.

Integration in the global front against imperialism

Let’s save the human race – let’s finish off the empire (Hugo Chávez)52

The achievements of the Bolivarian Revolution in terms of the wellbeing of the Venezuelan people are impressive in their own right, but the revolutionary process in Venezuela also has a wider – global – significance that deserves attention. I have written in some detail on this subject,53 so I’ll stick to a brief overview here.

Hugo Chávez had a very clear and far-sighted worldview, informed by his rich knowledge of world history, his identification of US-led imperialism as the major obstacle to peace and development, and his own experiences of trying to exercise sovereignty and build Venezuelan socialism in the face of destabilisation and CIA-backed coup attempts. He saw Venezuela as part of a global movement challenging half a millennium of colonialism, imperialism and racism; a global movement that included China, Brazil, Russia, Zimbabwe, Libya, Syria, South Africa, Cuba, Belarus, Vietnam, Iran, Ecuador, Bolivia, DPR Korea, Nicaragua and elsewhere. This thinking is reflected in the internationalist outlook of the Venezuelan state from 1999 until the present day.

Venezuela is a leading proponent of multipolarity – “a pattern of multiple centres of power, all with a certain capacity to influence world affairs, shaping a negotiated order”.54 Chávez linked multipolarity to Simón Bolívar’s concept of regional unity: “Bolívar spoke of what today we call a multipolar world. He proposed the unification of South and Central America into what he called Greater Colombia, to enable negotiations on an equal basis with the other three quarters of the globe. This was his multipolar vision.”55

Recognising that maximum coordination is necessary in order to effectively stand up to US imperialist domination, the Venezuelan state has been at the forefront of the effort to build an organisational and economic structure for regional integration of Latin America and the Caribbean. This effort has included the creation of the anti-neoliberal trade agreement ALBA (the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America),56 the regional bloc CELAC (Community of Latin American and Caribbean States)57 and the trade bloc UNASUR (Union of South American Nations). This cooperation reached its high point in the late 2000s and early 2010s, when progressive governments were in power in Venezuela, Cuba, Brazil, Ecuador, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Argentina, Chile and Uruguay; these governments achieved an unprecedented level of coordination and cooperation. Unfortunately, efforts to promote regional integration have suffered severe setbacks in the last few years, particularly with the judicial coup against the PT-led government in Brazil58 and the about-turn of the Lenín Moreno government in Ecuador,59 alongside electoral reverses in Argentina and Chile. Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay and Peru have now left UNASUR and set up an alternative, PROSUR, an initiative led by the US-aligned reactionary governments of Chile and Colombia.60

For decades a client state of the US, Venezuela in the last 20 years has focused on developing strong relationships with countries around the world, particularly those states that are amenable to mutually beneficial cooperation. Miguel Tinker Salas notes that, “in the past Venezuelan politicians seldom ventured from travel between Caracas and Washington, occasionally visiting New York and the United Nations, but never including Beijing, Moscow, Brasilia, Buenos Aires, and much less Tehran or Luanda, Angola on their itinerary. Now they do so frequently. Although the United States is still an important market for its oil, Venezuela no longer privileges relations with Washington, and instead promotes ties and pursues investments from countries as distinct as Brazil, India, Iran, Russia, and China.”61

Chávez clearly saw China in particular as a crucial partner in the struggle for a new world, visiting six times over the course of his presidency and forging close economic, diplomatic and political relations. In China, the Venezuelan leadership has found an inspiring example of what it’s possible for a developing country to achieve when freed from the domination of imperialism. Visiting Beijing in 2006, Chávez praised China for having converted itself from a “practically feudal” society into a world-leading economy in the space of a few decades. “It’s an example for western leaders and governments that claim capitalism is the only alternative. We’ve been manipulated to believe that the first man on the moon was the most important event of the 20th century. But no, much more important things happened, and one of the greatest events of the 20th century was the Chinese revolution.”62 The burgeoning political relationship has been matched in the economic sphere, with China providing billions of dollars worth of oil-backed loans,63 thereby allowing Venezuela to diversify its buyers and China to diversify its suppliers – key strategic goals in both cases. The extensive Chinese loans have been crucial in terms of financing Venezuela’s social projects.

Tinker Salas writes: “Hoping to strike a balance in its international affairs, Caracas endorsed economic arrangements with China, Cuba, Iran, and Russia, especially in areas such as health, telecommunications, auto manufacturing, oil explorations, and the production of machinery. The Chinese constructed and launched into space Venezuela’s two orbiting telecommunication satellites. Iran operates a tractor and car factory in the country and the Russians have become one of the leading arms suppliers of the Venezuelan military… As part of a policy to promote South-South relations, the country expanded diplomatic relations with most countries in Africa and in 2009 hosted the Africa-South America summit.”64

Beyond mutually beneficial economic relations, Venezuela has also provided strong diplomatic and practical support to liberation movements worldwide (for example Palestine65 and Western Saraha66), and has stood firm with those states in the direct crosshairs of western imperialism, most prominently Syria67 and Libya.68 Additionally, it has sought to build good relations with progressive forces in the imperialist heartlands, including with the London Assembly during Ken Livingstone’s tenure as mayor.69

A friend in need

“They choke us and they ask us, why are we suffocating?” (Nicolás Maduro)70

The Bolivarian Revolution in Venezuela is currently facing its biggest challenge to date, one that poses a mortal danger. In 2013 it was hit with two major blows: the death of Hugo Chávez and the collapse of international oil prices. Those two factors combined to create a fragile situation which the Venezuelan elite and its US backers sought to take advantage of.

Chávez’s untimely death was a terrible setback. To millions of Venezuelans, he embodied the revolution, and the whole process was defined to a significant degree by his vision, determination, boldness and charisma. Thankfully there are many capable leaders in the Venezuelan state, and 15 years in power was sufficient to develop a strong cadre at all levels of government. Chavismo has survived. Unfortunately oil prices have yet to substantially recover. Oil provides 90% of Venezuela’s export income and 50% of government revenues. Reduced fiscal income means reduced service provision, which leads to popular dissatisfaction. Steve Ellner remarks that “oil prices under Maduro have not only been low since 2014 but nosedived, just the opposite of what happened under Chávez. This is particularly problematic because high prices create expectations and commitments that then get transformed into frustration and anger when they precipitously drop.”71

Of course, the continued heavy reliance on petroleum income highlights the failure to date of the Venezuelan socialist project to meaningfully diversify its economy. The fact is that Venezuela has been a petro-state ever since the discovery of massive oil reserves in the Maracaibo Basin a century ago. The government can probably be criticised for not investing more in diversification during the decade or so when oil revenues were unusually high. Kicking the oil habit is unquestionably difficult, and may well require several more decades, but it will be indispensable to the survival and advance of Venezuelan socialism.

With the economy in trouble, the US and its local allies didn’t waste any time driving the knife in. As Venezuelan Minister of Foreign Affairs, Jorge Arreaza, writes: “Imperialist actors have sought, by any means available to them, to overthrow and eliminate the Bolivarian Revolution, to retake political control of the country, so that the riches of Venezuelans can once again be used as tribute to benefit transnational capital.”72 Domestically, the opposition parties – wealthy, white, pro-US and fanatically anti-Chavista – stepped up their efforts to make the country ungovernable, organising violent demonstrations, spreading lies (through their domination of print and television media) and hoarding goods so as to create shortages and drive inflation. The US has added to this pressure with wide-ranging sanctions – “a savage and criminal financial and commercial blockade.”73

The sanctions are designed specifically to cause hardship among ordinary Venezuelans and to break their support for the Bolivarian Revolution. The calculation is, needless to say, that worsening conditions will lead to the downfall of the Chavista government and ultimately the rolling back of the socialist advances of the last two decades. Certainly the sanctions are already wreaking havoc. World-renowned economist Jeffrey Sachs states plainly that “American sanctions are deliberately aiming to wreck Venezuela’s economy and thereby lead to regime change. It’s a fruitless, heartless, illegal, and failed policy, causing grave harm to the Venezuelan people.” Mark Weisbrot and Jeffrey Sachs published a report in April indicating that sanctions to date have led to 40,000 deaths as a result of food and medicine shortages.74

It would be difficult to overstate the importance of defending Venezuela. Defending Venezuela means supporting the second wave of socialist advance; it means defending the gains of two decades of hard-won progress; it means maintaining the trajectory towards a multipolar world; it means challenging the US’ attempt to reimpose the Monroe Doctrine.75 In 2015, the Argentinian sociologist Atilio Boron wrote powerfully about the critical importance of the Bolivarian Revolution: “The struggle being waged in Venezuela today is decisive not only for this South American country, but for all the emancipatory processes underway in Latin America and the Caribbean… What we are waging, in the homeland of Bolívar and of Chávez, is our battle of Stalingrad. If the oligarchic-imperialist reaction is successful in its efforts, all of Latin America will feel the heavy blows… It will be a terrible lesson against the countries whose governments had the audacity to defy the empire.”76 These words continue to resonate.

Those of us around the world who support socialism, who defend the right of nations to self-determination, who oppose imperialist domination, have a duty to stand up for Venezuela. The world needs more socialist-oriented states, not fewer! We must apply pressure to our governments not to participate in sanctions or other forms of economic destabilisation. We must resolutely oppose any threat of military intervention. Those whose governments have signed up to the US-led regime change agenda must demand those governments stop supporting Juan Guaidó’s attempted coup and that they limit their involvement to supporting peaceful dialogue. We should work hard to raise awareness, to refute the pervasive lies and slander that appear in the media (including the supposedly left-leaning press – The Guardian is among the worst offenders when it comes to Venezuela). We should support independent media groups such as Venezuela Analysis that are working to counter the relentless information warfare.

Let’s be inspired by the US activists who put themselves in the firing line in order to protect the Venezuelan embassy in Washington.77 Those in Britain should join and support the Venezuela Solidarity Campaign.78 Those in political parties should pass resolutions calling for an end to sanctions and destabilisation. The further the message spreads, the better. Let’s do everything we can to defend Venezuela.