In the four months since it launched, the No Cold War campaign has been working hard to unite diverse forces worldwide against the US-led New Cold War on China. Following its inaugural conference and the launch of its statement in July, the campaign has hosted an international peace conference, a dialogue between professors Jeffrey Sachs and Zhang Weiwei, a webinar analysing the impact of the presidential elections on US-China relations, and, on 14 November 2020, a webinar entitled ‘Uniting against racism and the New Cold War’.

Introducing the event, Sean Kang from the Qiao Collective noted that, since the start of 2020, the world had witnessed a dangerous deterioration in US-China relations. In the US, this escalation of tensions has been accompanied by a rise in racism against Asian-Americans, with the government seeking to shift the blame for the pandemic onto China, using racialised terms such as China plague’ and ‘Wuhan virus’. Meanwhile the pandemic has further exposed the racial fault-lines in US society, with indigenous, black and Latinx communities suffering particularly badly. This combination of factors demonstrates the tight bond between racism and imperialism, which is the major theme of this webinar.

Danny Haiphong, senior contributing editor with Black Agenda Report and member of the No Cold War organising committee, pointed out that Cold War politics and racism are connected by their shared vision: preserving the hegemony of US-led capitalism. There are some parallels with the original Cold War. After the “loss of China to communism” in 1949, the US moved quickly to impose sanctions and a military blockade, and China encirclement was one of the motives for the Korean War. During that war, racism was used to provide cover for the extreme brutality of the US-led forces, which included the first systematic use of napalm against a civilian population.

Danny noted that African-American activists in particular took a strong stance against the Korean War, and many – including very prominent figures such as Paul Robeson, WEB DuBois and Claudia Jones – were inspired by the possibilities of People’s China. Many saw China as a place of refuge from the threat of white imperial rule, and indeed the well-known civil rights campaigners Robert and Mabel Williams fled to China after being driven out of the US by white supremacists. Danny stated that the original Cold War used racism to dehumanise peoples choosing their own path of development in Asia, Africa and Latin America. The New Cold War employs similar same logic. Danny urged progressive people in the West to model peaceful relations, to denounce the New Cold War, to extend a hand of friendship to China, and to open up to a multipolar world.

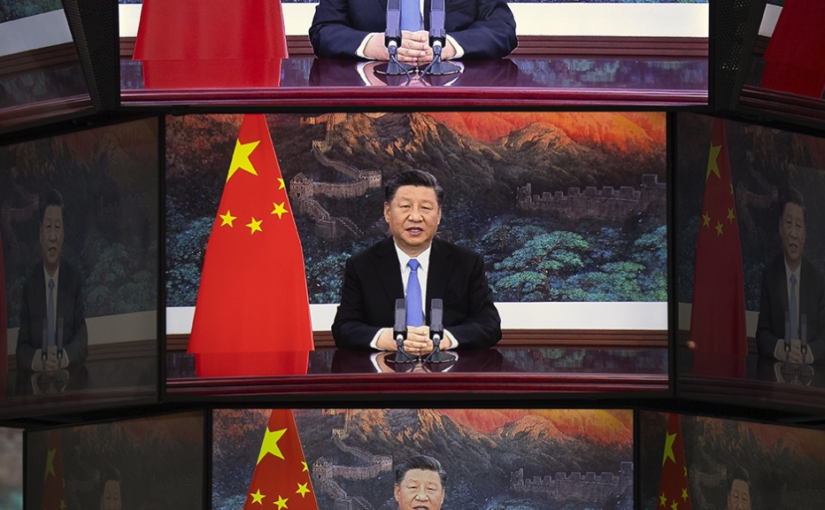

British-Iraqi rapper and campaigner Lowkey noted that China’s rise in recent decades is serving to restore a global balance of forces that, until the industrial revolution, had been in place for more than a thousand years. China was producing steel 1.5 millennia before England was; it had movable type printing technology 500 years before England did. It had theories of meritocratic governance embedded in the Confucian system long before Europe’s feudal autocracies were overthrown. As such, within the long view of history, China’s re-emergence as a major global power should be nothing to fear.

Lowkey pointed to China’s remarkable progress over the last few decades. In 1978, China accounted for 5 percent of global economy, and 80 percent of Chinese people lived in poverty. By turning itself into the world’s biggest manufacturing power, China has been able to lift 750-800 million people out of poverty, accounting for two-thirds of global poverty reduction in that period. Some prominent economists predict that, by 2030, China will constitute one-third of the global economy. And importantly, China’s rise is taking place in conjunction with the rise of the rest of the developing world. Of the top 20 fastest growing economies, not one of them is in the ‘developed’ world, and this Global South development is to a significant extent being financed by Chinese development banks.

There’s a significant danger that, facing long-term decline and short-term crisis resulting from the pandemic, the US will turn to war and, in so doing, leverage the Yellow Peril racism that has been invoked multiple times in the last 150 years. The US will also try to pull Britain into its camp in opposing China. Lowkey stated that Britain would be shooting itself in the foot if it joined in the New Cold War, and should instead build a strong cooperative relationship with China.

Chinese journalist Li Jingjing gave her perspective on the protection of minority rights in China, responding to the stories she has come across in Western media accusing the Chinese state of wiping out minority cultures, destroying mosques, and so on. Having travelled extensively within China, Jingjing said the portrayal of human rights abuses was entirely out of step with reality, as the government is very proactive about supporting and protecting minority cultures. She said that the constitution recognises 56 different ethnic groups, and there is a vast body of legislation supporting each group’s rights and autonomy at local and regional levels.

The law mandates that minority languages be taught in the various autonomous regions. Jingjing said she had recently visited Tibet, and saw that all school students (including Han Chinese) have to learn Tibetan at school. She said that the stories of forced sterilisation of Uyghur women couldn’t be further from the truth; in fact the One Child Policy had only applied to Han people, and the Uyghur population has tripled in the period of existence of the People’s Republic of China. In her opinion, the real story about ethnic minority human rights in China is that poverty is being wiped out. However, this doesn’t fit with Cold War propaganda and therefore receives minimal attention in the West.

Beijing-based journalist Cale Holmes pointed to the gradually rising tensions between the US and China since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Part of the Nixon administration’s motivation for pursuing links with China in the 1970s was Cold War ‘triangulation’ against the USSR. With the collapse of socialism in Europe between 1989 and 1991, the US-China relationship thus lost some of its strategic value for the US. Although strong economic ties remain, US strategists recognise that China hasn’t conformed to the Washington Consensus; that it is an independent power that is responsive primarily to its own people.

Cale warned that a rising anti-Asian racism in the US is making the idea of military conflict with China more palatable to the US public. Any such conflict would be extremely dangerous for China, for the US, and for the world. Meanwhile China is pursuing multilateralism and international cooperation. For example, it has been very active sharing its resources and experience with African countries to aid their pandemic containment efforts. This is the type of international cooperation we should be building towards.

Activist and retired NBA all-star David West contrasted the US’s pandemic response with that of other countries such as China, Senegal and New Zealand. The utter failure of the US authorities to protect human life in the pandemic shows us what happens when profit is the determining factor in practically all areas of life. Hyper-capitalism, poor leadership and mixed messaging have combined to produce disaster. Meanwhile countries like Cuba and China are sharing medical expertise, personnel and supplies with other countries, modelling the type of collective spirit the world needs.

As a global community we have shared interests more than ever before. David pointed out that, facing common problems of an impending climate catastrophe, wars, pandemics and global poverty, the countries of the world must work together for the sake of humanity’s survival. There’s nothing to be gained and too much to lose in a Cold War. All nations must take the path of peace, of justice; that’s what the people of the planet strive for. We’re all interconnected and a shared future is the only way forward.

Lebanese-American journalist Rania Khalek discussed the threat posed by China to US unilateralism and domination. China is increasingly at the forefront of new technology – particularly in telecommunications – and this is a big threat to US profits. Furthermore China is starting to create new financial infrastructure to get around the US dollar, thereby challenging dollar hegemony. At an ideological level, China offers an alternative model to neoliberalism. This is particularly relevant for developing countries, which can see that China has been able to achieve huge successes in improving living standards via a decidedly non-neoliberal model.

The US wants to maintain economic dominance and unilateral political control. China stands in the way of both, hence the bipartisan consensus against China. China also provides a useful excuse for the US’s military-industrial complex to expand; it’s the scary boogeyman that can be used to justify enormous military expenditure. Meanwhile the trade war and the military encirclement are being supplemented with a propaganda war. The US will continue to leverage issues such as Hong Kong and Xinjiang to attack China, and it’s very important people look at these issues with a sceptical eye and understand the underlying Cold War dynamics.

Chris Matlhako, coordinator of the South African Peace Initiative and Deputy Secretary of the South African Communist Party, talked about the struggle against apartheid, noting that although South Africa was a global pariah, it received support from the US, Western Europe, Australia and Japan. However, a truly global movement emerged to oppose apartheid, to fight against racism and imperialism. Chris called for the construction of a global network against racism and war, across political divides. He said the anti-apartheid movement should be studied, as it was able to mobilise diverse progressive opinion from around the world.

Chris highlighted the growing possibilities for the Global South as a result of the rise of China and the emergence of BRICS and other multilateral frameworks. One particularly important example of international cooperation in recent times is the collaboration between China and Cuba on treatments for Covid-19. This is great news for the Global South, helping people to access medicines and to overcome the issues of intellectual property that continue to tie profit maximisation to scientific development and the improvement of people’s lives.

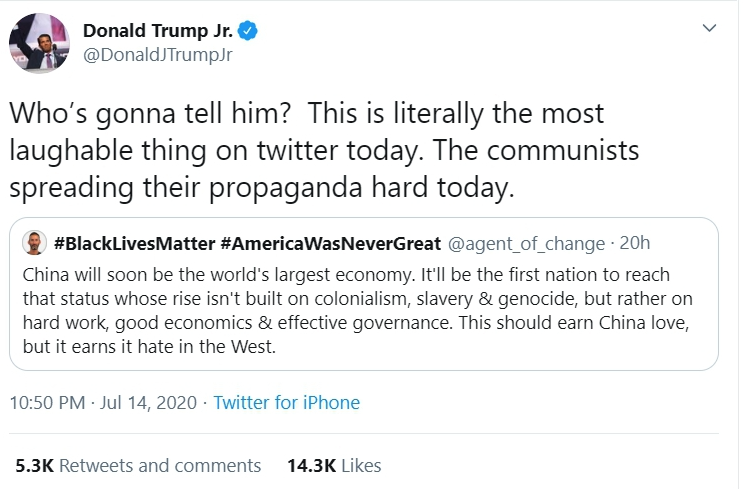

Chinese-American activist Lee Siu Hin, founder of the National Immigrant Solidarity Network, said that another virus is spreading alongside Covid at the moment: that of the New Cold War and the demonisation of China and Chinese people. This has dovetailed with a rise in racist and xenophobic sentiment throughout the world, a phenomenon both reflected in and exacerbated by the election of Donald Trump in 2016.

Siu Hin said that the US has been using every opportunity to try and destabilise China. At the end of last year, it was clear that the unrest in Hong Kong wasn’t going to have the desired effect of undermining the domestic popularity of the Chinese government. Meanwhile the trade war hadn’t meaningfully impacted China’s economic growth. So the pandemic provided a new opportunity to ramp up the Cold War. US policymakers thought China wouldn’t be able to control the virus; that the economy would collapse; that Chinese citizens would be furious. In reality, China was able to get Covid-19 under control within 2-3 months. Siu Hin said that he’s currently in China and that life has returned to normal. That this was possible highlights China’s prioritisation of the needs of its people, while the US consistently prioritises war and repression.

Indigenous American academic and activist Nick Estes talked about the parallels between the West’s handling of Covid-19 and its handling of climate change. As with the climate crisis, the most advanced capitalist countries had plenty of warning to get organised in advance of the pandemic, had access to the best science, and then did nothing, preferring to protect the wealthy and shift any blame onto others. Much like with climate change, the brunt of the current public health crisis is being borne by black, brown, indigenous and migrant communities. Once it was clear the virus was disproportionately impacting these communities, large groups of predominantly white and right-wing people started storming state capitols demanding the reopening of restaurants.

Nick pointed out that US militarisation of the Pacific – the centrepiece of its China containment strategy – is taking place on occupied lands. RIMPAC (the Rim of the Pacific Exercise) is a set of biennial war games organised by the US Navy Pacific Command (PACOM), with participation from US allies including Canada, Japan, New Zealand, Australia and France. These games are conducted in Hawaii – a nuclearised ‘paradise’ and occupied territory at the centre of the Pacific militarisation project. Guantanamo Bay, Guam and Okinawa are in a similar situation. Indigenous land activists are calling for the dismantling of this military infrastructure and for the return of the land to its rightful owners.

Author and activist Carlos Martinez wrapped up the event on behalf of the No Cold War organising committee. He pointed out that ongoing economic stagnation, alongside the failure of the major Western countries to contain the pandemic, is producing a crisis of legitimacy and a corresponding sense of panic among the ruling class, which is responding by hitting out in all directions. He said that the US and its allies are struggling to come to terms with China’s rise. China is a politically independent country, a Global South power with a Communist Party government and an essentially planned economy. As such, it poses an existential threat to the prevailing world order based on neocolonialism, neoliberalism and white supremacy.

Carlos emphasised that the emergence of a New Cold War concurrent with a worrying rise in racism is no coincidence. Both are manifestations of neoliberal capitalism in crisis, and both are being deployed in an attempt to preserve a system based on the needs of a wealthy elite at the expense of the vast majority of humanity.

Carlos thanked the speakers and organisers, and encouraged everybody to sign the No Cold War campaign’s statement, ‘A New Cold War against China is against the interests of humanity’.

The full event can be viewed on YouTube.